Beat Elegy

Death laid at the door of the Beat Generation in 1958 San Francisco.

It was 3:45 a.m. on June 15, 1958.

The party was almost over. The police had arrived and were hustling people out of Eric Nord’s “Party Pad,” a BYOB affair that Nord thought would be his last at 126 Oregon Street.

The party was also almost over for the ramshackle building and for Oregon Street itself. Soon the old produce district would be scraped away by the Redevelopment Agency for the “Golden Gateway.” The three-block alley of Oregon Street would disappear forever, replaced by apartments and townhouses.

The party was definitely over for Paul Swanson. He swayed on the ledge of the roof, which was littered with mattresses, lawn chairs, whiskey bottles, and beer cans.

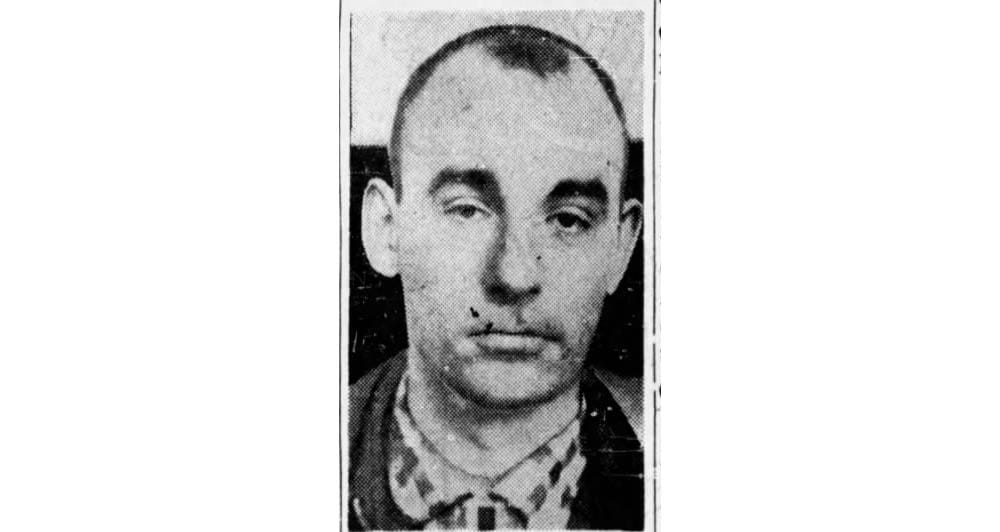

Swanson was a cab driver, saxophone player, and a poet. Four months earlier, he had been at Napa State Hospital being treated for alcoholism. Special police officer Archie Davis saw Swanson teeter and then tumble backwards into the building’s lightwell, falling two and a half stories to his death.

The newspapers reported the accident as a Beat Generation death. “The ‘beatsters,’ following their philosophy of hopelessness,” wrote the San Francisco Examiner the next day, “were casual about Swanson’s death plunge.”

A Stormy Relationship

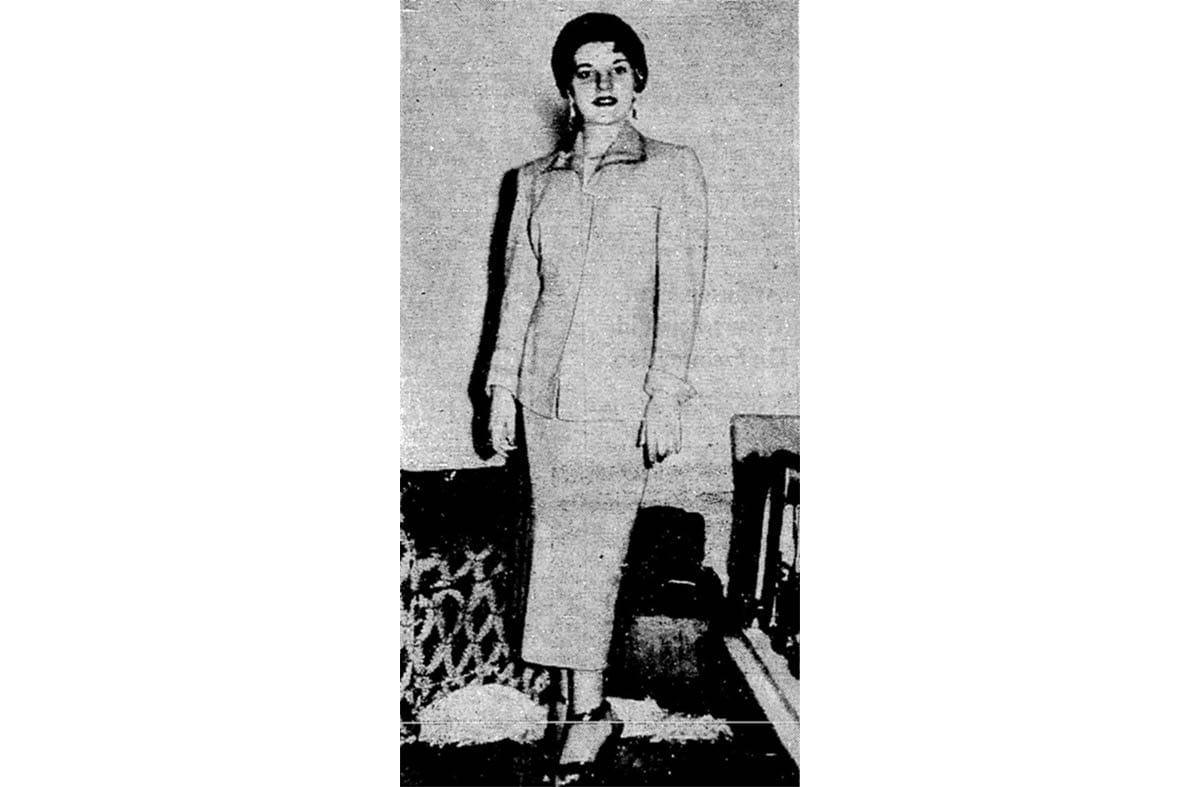

Connie Sublette, aka Dana Lewis, aka Connie Alioto, was not casual.

The 20-year-old was loud and dramatic, especially when drinking. She was reportedly orphaned at two years old and spent time in a home for delinquent children in Oregon before coming to San Francisco. She was often drunk and she was often sad.

Her current last name she owed to common-law husband Albert Sublette, with whom she had lived for two years on Broadway. They had split. She had been trying on “Connie Swanson” because she considered Paul Swanson her fiancé.

A couple of months before, at three in the morning, she stormed from Swanson’s room and out the front door of the Milano Hotel at 426 Broadway.

She was incensed. She was also naked.

After hustling her back inside, the management informed Sublette she could not continue to stay at the hotel.

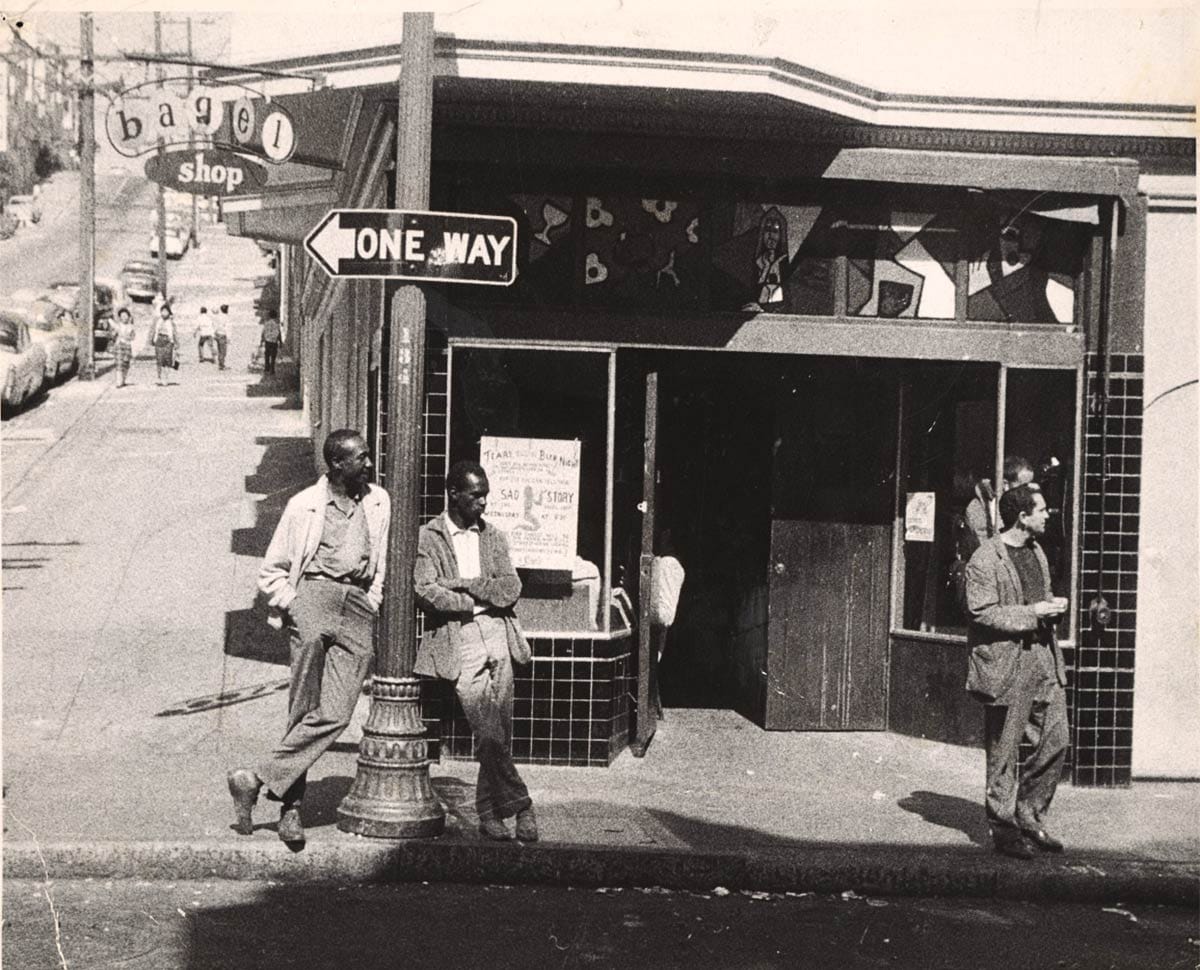

A few weeks before Swanson’s death, the couple had a loud row outside the Co-Existence Bagel Shop on the corner of Green Street and Grant Avenue.

“She had a reputation of screaming at people… She also was an alcoholic.” said Jay Hoppe, owner of the bagel shop, which was described as a “beatster bistro” by the Examiner.

“They had a stormy relationship,” said James Parry, a friend of both Swanson and Sublette.

Now Swanson was dead. On Tuesday, June 17, two days after Swanson’s fall, Parry gave Sublette a ride to the Halsted funeral parlor on Sutter Street to view the body. She placed a rosary on the chest of her poet/musician/cab driver fiancé. Around her own neck she wore a medal of St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers.

Parry and Sublette returned to North Beach. She drank in mourning along Upper Grant Avenue the rest of the day and hung out at the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, the site of her big fight with Swanson.

Around 11:00 p.m., she asked for a ride to her ex’s place at 428 Lyon Street. She had shown up at Albert Sublette’s doorstep drunk on other late nights. At least once he had to call the cops to get rid of her.

Albert wasn’t home. Connie decided to sit on the steps in the dark and wait. She didn’t wait quietly. The landlord, Pedro Palapay, told her to pipe down or he’d call the police.

Good Advice

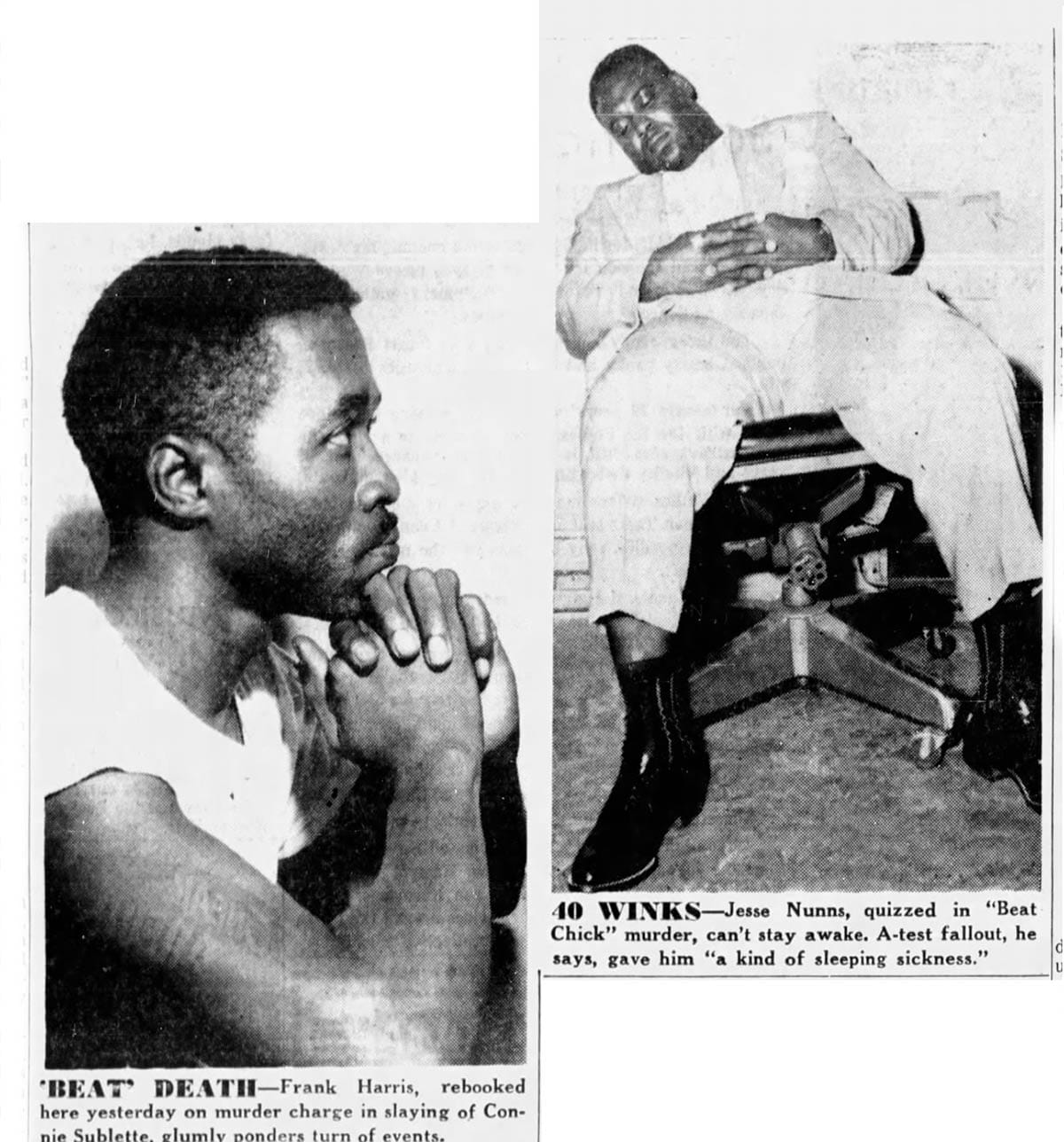

Jesse Nunns of the USS Gaffey had a hard time staying awake. Since a stint near the Enewetak Atoll in the Pacific the sailor thought he suffered from a “sleeping sickness” caused by A-bomb test radiation.

But he still was able to run a sideline business selling mail-order suits. He had just sold one to Frank Harris, a civilian laundryman on the same transport ship. Just as they came into port in San Francisco, he wrote up a $14 receipt for the order.

Harris had a new suit coming, but he also had a heroin addiction. He went out the night of June 17, got a fix, and ended up drinking a pint of whiskey as well. Unable to sleep in his apartment away from the ship at 448 Scott Street, he decided to take a walk.

He saw Connie Sublette slumped on the steps of 428 Lyon Street and approached after the landlord warned the noisome Connie to be quiet. “That’s good advice,” he said, sitting beside her on the staircase.

Harris told the drunk woman he’d get her a taxi, got her up off the steps, and then turned into an alley accessing a back yard residence next door at 436 Lyon Street.

“I started to caress her. She didn’t resist at first and I thought it was going to be easy.” The laundryman removed his coat and most of Sublette’s clothes before she started yelling.

“I was afraid she would attract attention and the police would come. Then I’d be in trouble.”

Harris put his handkerchief around her mouth to quiet her. The improvised gag slipped off her mouth and around her neck, right over the St. Christopher medal.

“I just kept on squeezing.”

When she went limp, Harris thought she’d passed out. He grabbed his coat and ran.

Expected

Connie Sublette was found dead in the alley at 6 a.m. She lay on her coat, wearing nothing but her black bra. The rest of her clothing hung neatly on a wire gate. Doctors reported she hadn’t been raped. Her neck was a bruise of whorls from the St. Christopher necklace.

Under Sublette’s body, detective Al Nelder discovered half of the torn receipt for the suit. It led him to the sleepy Jesse Nunns, who identified it as given to customer and shipmate, Frank Harris.

The detectives moved quickly and just in time. The USS Gaffey sailed for Yokohama while the two men sat in police headquarters being questioned.

While Nunns slept in a chair, Harris confessed to the killing. He handed the other half of the suit receipt to the detectives. He told Nelder that after he had read the news that Sublette was dead, “I had expected you.”

Harris pled guilty to first-degree murder hoping for a life sentence instead of the gas chamber. The District Attorney and judge believed he killed Sublette accidentally and gave him his wish, a life sentence, on October 16, 1958.

Every Kind of Delinquency

To the newspapers, Sublette’s death meant something needed to be done about the North Beach Beat scene, even though Connie wasn’t killed in North Beach and her killer said he’d never heard of the Beat Generation.

Each person involved was described in a snide connecting way to Beats. Albert Sublette was a “frustrated poet, messenger boy and back-sliding Beatnik.” Friend James Parry, who drove Connie to the funeral parlor, “worked at a Fisherman’s Wharf crab stand when not dissecting civilization with the Beatniks.”

The dead Paul Swanson had been an “unemployed cab driver,” “a musician of sorts and a poet of parts,” while victim Connie Sublette was a “playgirl,” a “starry-eyed debutante of the ‘Beat Generation,’ and a “free-living and loving North Beach Beatnik.”

With her tragic death, a troubled and somewhat annoying presence in North Beach was elevated to Example A of what happens to those who follow existential Beats. Columnists as far as Miami lapped it up. Her killer was given more sympathetic treatment in the press than Connie Sublette.

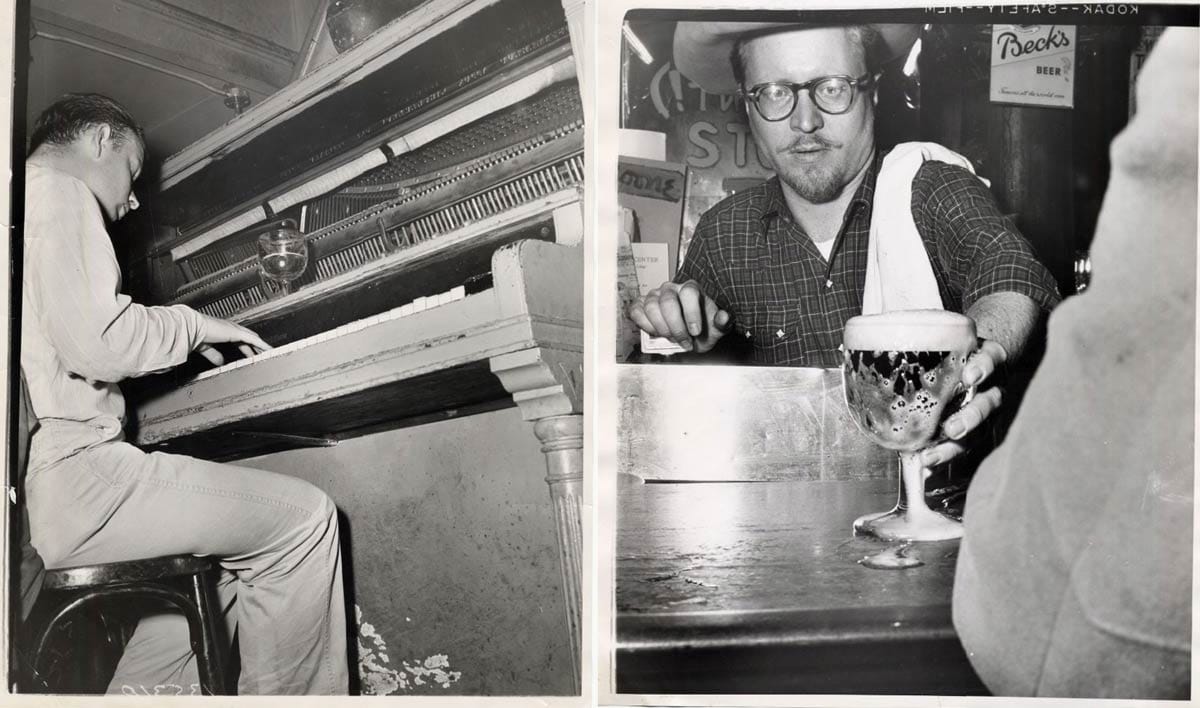

Mayor George Christopher and the police agreed to keep an eye on things in North Beach. Christopher said that Beat Generation was “a fancy name to glorify every kind of delinquency.” The police increased patrols and their surveillance of Grant Avenue hangouts.

An undercover Chronicle reporter (who certainly grew a goatee for the job) spent four months in North Beach to share insights like “The Beatnik, after arising, may or may not brush his teeth. He probably will not wash and almost certainly will not shave.”

Some out-of-town newspapers hearing the news of Sublette’s death weren’t up to speed on the anti-hipster angle. An Atlanta editor reached out to the Examiner over the wire service asking for the definitions of beatnik and Beat Generation.

The paper also had a question for a story angle it did understand: “Connie Negro or white, pls?”

In the South, a black man killing a black woman wasn’t a story. A black man killing a white woman was.

Finest View

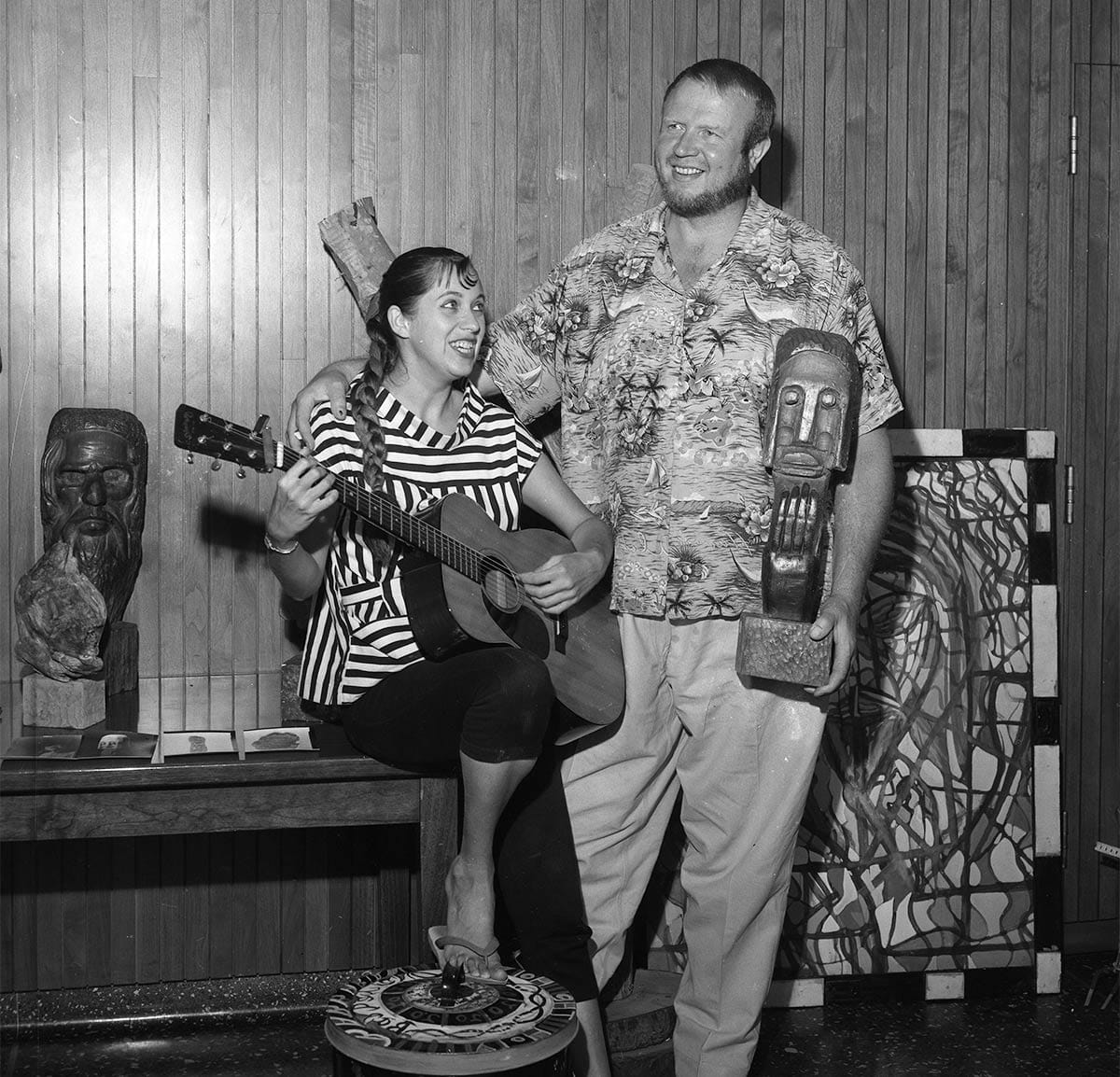

The District Attorney allowed Eric Nord to keep his Party Pad going on Oregon Street a while longer. The bearded and beret-ed Nord promised to clean the place up and get some garbage containers. “I have a nice summer program planned—poetry reading, music, yoga.”

Chester Arthur, grandson of the 21st president of the United States, threw his own bash at Nord’s place two days after Swanson fell to his death and the same night in which Connie Sublette would be strangled. His guests mostly hung out on the roof around the deadly lightwell.

Columnist Herb Caen, credited with popularizing the term beatnik earlier in the year, was not subtle describing the irony of the scene:

“While a special cop detailed the tragedy, the sound of conga drums floated up into the night, a young couple writhed under the stars and Chester stood aloofly at a corner, gazing at the skyline and murmuring ‘Finest view in all San Francisco.’”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to Ted B. (F.O.W.) for his contribution to the not-a-scam fund to make me have drinks with nice people. Cool to have donors from Cornwall, England...

Chip in, if you like. Whether you do or do not, all are free to take advantage of the fund. When are you free to join me?

Sources

“Poet of ‘Beat Generation’ Dies at Party,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 16, 1958, pg. 1.

Peter Kimble, “Killer Says ‘Beat’ Girl Spurned Him,” San Francisco Examiner, June 19, 1958, pg. 1.

June Muller, “To North Beach Hipsters, Death Comes in Threes,” San Francisco Examiner, June 19, 1958, pg. 1.

“S.F. Slain Girl Orphaned at 2,” San Francisco Examiner, June 19, 1958, pg. 11.

George Draper, “‘Beatnik’ Girl Slain by Seaman Looking for Love,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 19, 1958, pg. 1.

“Party Pad, Scene of 1 Death, Can Stay Open,” San Francisco Examiner, June 19, 1958, pg. 11.

William Tuohy, “‘I’m Sorry for Her,’ Says Girl’s Killer,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 19, 1958, pg. 6.

Allen Brown, “Connie was Renowned for a Race in the Nude,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 19, 1958, pg. 7.

Allen Brown, “Police Keep Close Watch on Beatniks,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 20, 1958, pg. 1.

“Police Cold War on Beatniks Bared,” San Francisco Examiner, June 20, 1958, pg. 14.

Herb Caen, “Friday Fish-Fry,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 20, 1958, pg. 20.

“Dancing Death,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 22, 1958, This World section, pg. 3.

Allen Brown, “Life and Love Among the Beatniks,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 22, 1958, The World Section, pg. 4.

Dick Nolan, “The City,” San Francisco Examiner, June 22, 1958, Section II, pg. 1.

“Girl’s Slayer Pleads Guilty,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 3, 1958, pg. 16.

“Strangler Given Life Sentence,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 17, 1958, pg. 2.