Cottages of Care

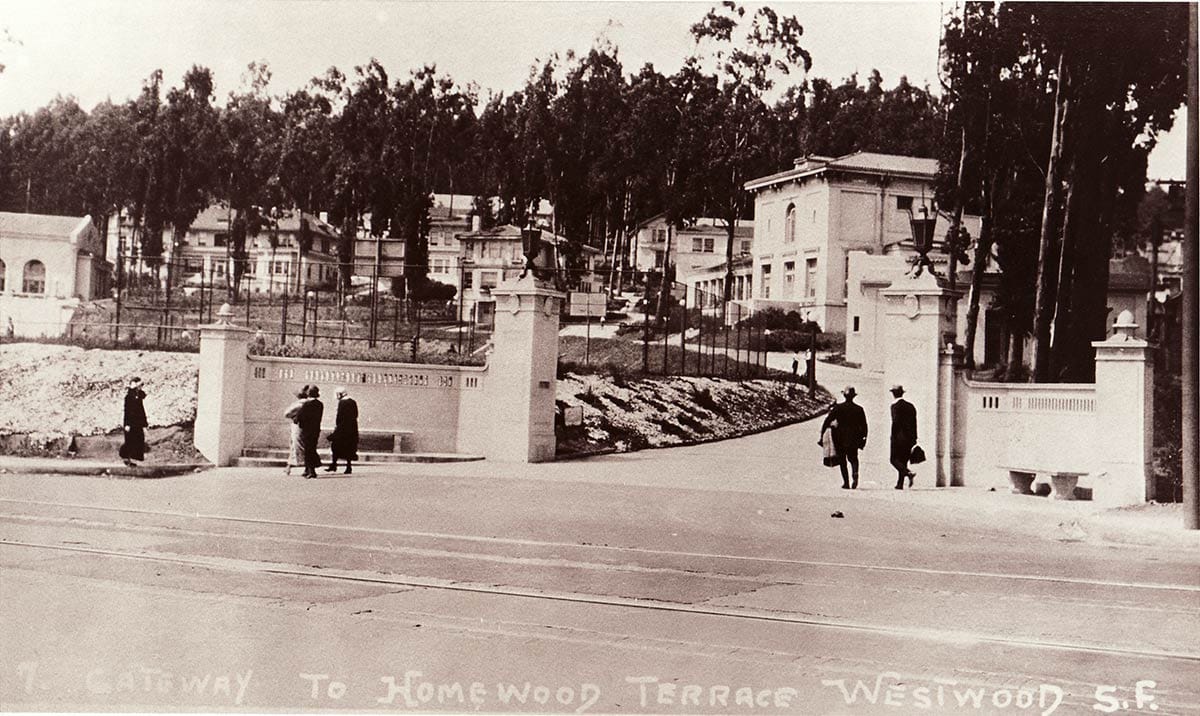

When San Francisco's Ingleside was a home to Homewood Terrace.

Since its construction in the early 1980s, the expansive housing and retail complex on the north side of Ocean Avenue between Keystone Way and Ashton Avenue has had its ups and downs.

The large retail spaces flanking Dorado Terrace have had a Safeway, a Rite-Aid, a Target, and the defunct Blockbuster chain all come and go over the years, and the vacant and walled-up retail spaces are dismal and dead compared to the floating apartments-of-arches and sherbet-colored townhouses above the street.

The layer cake of stucco walls and iron-fenced balconies may not a masterpiece of design, but most locals applauded its creation. The site had become overgrown and old crumbling buildings left on it were a fire and safety hazard. People were desperate for anything to be built.

According to the OMI News in 1973, the almost five acres of space could “only be described as an eyesore.”

But 50 years earlier, in 1920, the view inspired optimism and excitement. A new and inventive residential care facility for children, Homewood Terrace, was being dedicated.

The Pacific Hebrew Orphan Asylum and Home Society had been caring for Jewish young and the aged since the 1870s. At the dawn of the 20th century, its orphanage for children at Divisadero and Hayes streets had over 200 residents. (Such care was divided between religious and cultural groups in the city. You can read about the Presbyterian version here.)

The building was aging. Philosophies on education and institutional care of children were changing. The conscientious trustees of the Orphan Asylum were paying attention.

In planning to replace the old structure, the society decided to reorganize on what was called the “family” or “cottage” plan.

This new idea from the East Coast directed doing-away with large dormitory-style buildings evoking Oliver Twist. Instead, cottages emulating family homes, each with a supervising “house mother,” were proposed to provide shelter to smaller groups of children.

Ideally, the cottages would be situated in a rural setting where, as one romantic writer supposed, “a boy or girl must be indeed incorrigible who cannot find rest and sweetness in the call of a robin or savor of the new cut grass…”

Sold on the cottage plan, the trustees of the Pacific Hebrew Orphan Asylum debated through the 1910s whether to stay in the city (where the need was greatest) or relocate to the countryside (Where there was new cut grass). In the end, they split the difference by purchasing thirteen acres of Adolph Sutro’s forest in the somewhat suburban if not pastoral Ingleside area along Ocean Avenue.

In the 1920s, “orphan” was already considered a stigmatizing label conveying destitution and unworthiness. It was also an inaccurate description of many of the children in the care of orphanages. Alongside those with deceased parents lived dependents of the state whose parents were unable or unwilling to care for them, as well as children requiring a temporary supportive home in a time of family crisis or transition.

With their new facility, therefore, the Pacific Hebrew trustees dumped “orphan asylum” and came up with the refined “Homewood Terrace.” (Many upscale housing developments used “Terrace” in their names in the 1910s.)

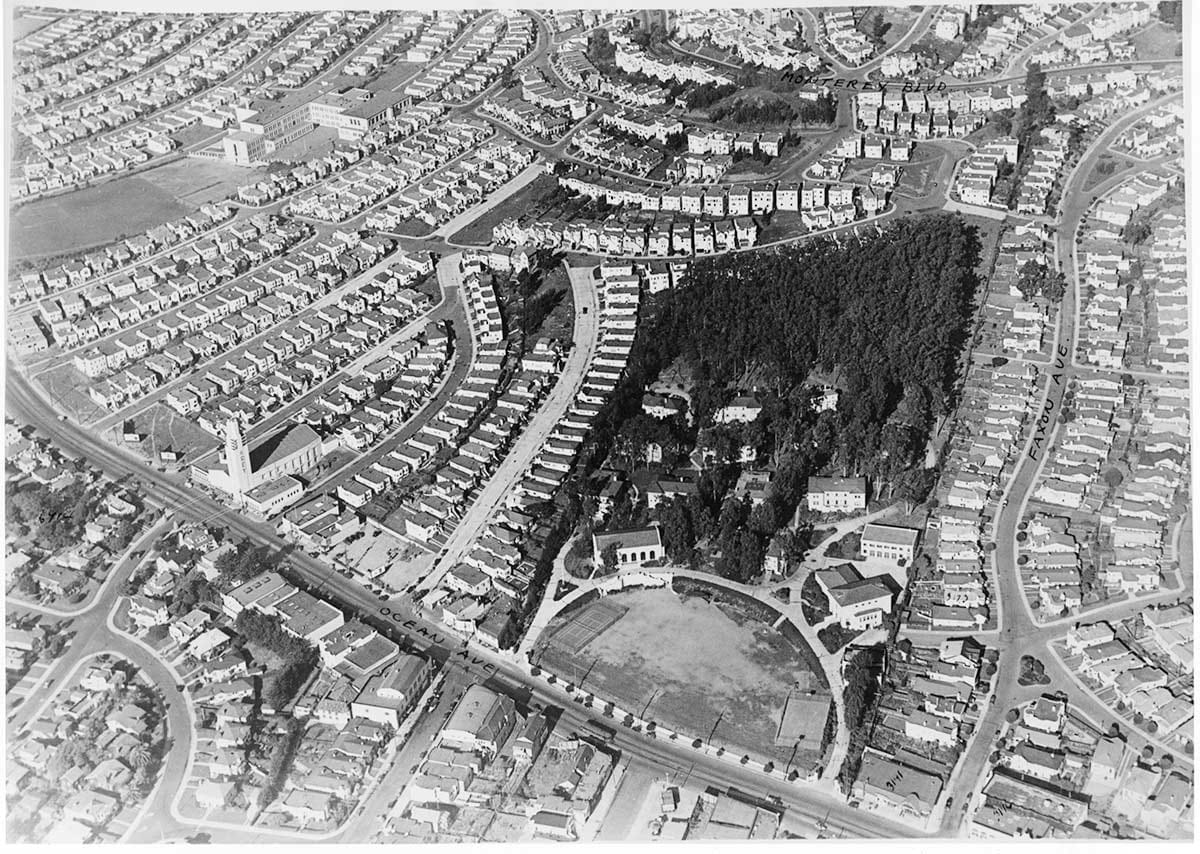

Alfred Henry Jacobs, architect of the new campus, designed a half-circle driveway entry from Ocean Avenue, with lawn, tennis and basketball courts set in the arc. Above the drive, amid Sutro Forest trees were an eventual seventeen buildings—nine residential cottages, an administration building, a gymnasium, a synagogue, a machinery shop, two superintendent residences, a small hospital, and a laundry.

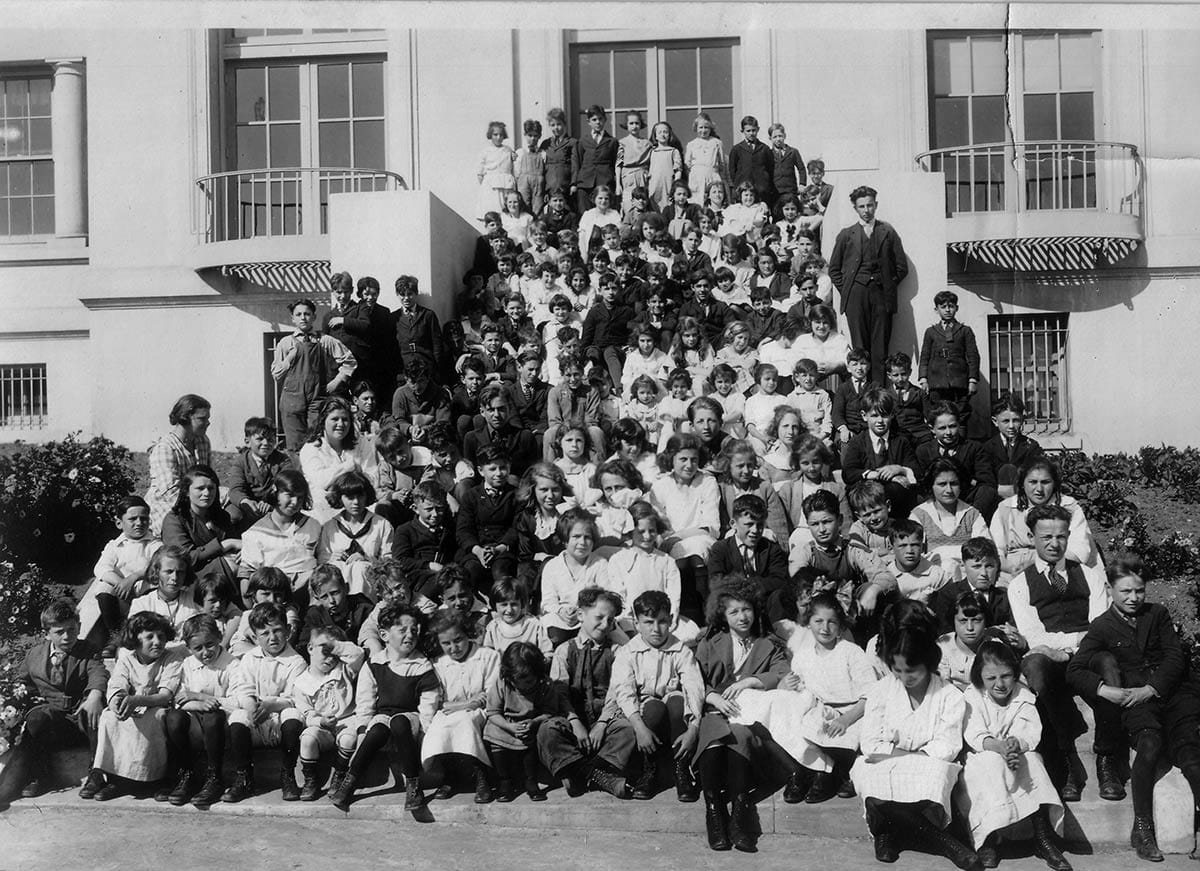

Each cottage housed twenty children—ten boys and ten girls ranging from toddlers to high school seniors—with a live-in cottage mother. Each residence had a kitchen, living room, and small library. Each resident had a locker, closet, and separate drawer space.

The institution’s 1922 report noted the change from dormitory life, that each child now had “[h]is own books, his own toys, his own clothes and his own private place for each, sacred to himself, to play or read or think, away from the milling mass.”

After Homewood Terrace opened in 1921, its residents became part of the Ingleside neighborhood. They attended nearby Farragut Elementary School, and later, Aptos Middle School. In less than five years over 320 individuals experienced cottage life on Ocean Avenue.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Homewood Terrace took in many children escaping from the Holocaust in Germany. Meanwhile, the forest around the campus disappeared under the carpet of new homes built for Mount Davidson Manor, Westwood Highlands, and Monterey Heights.

By the 1960s the standards for residential care for children had changed again. In some ways the cottage model proved a steppingstone to a more progressive foster system. Instead of just simulating home and family life, boys and girls were meant to truly live it. In 1965, the last residents of Homewood Terrace were relocated to seven “real” houses in the Richmond District, and the organization was folded into today’s Jewish Family and Children's Services agency.

Memories of former Homewood Terrace residents, most of whom experienced a turbulent and stressful childhood, are varied and complex. For some, Homewood Terrace was a welcome haven of security; to others it was an unpleasant place of strict rules and arbitrary punishments. Many remember a mix of good and bad.

Different development plans were proposed for the abandoned Ocean Avenue campus in the years following the closure of Homewood Terrace: a senior housing center with 19-story towers (1967), a 300-unit apartment complex (1970), and a more traditional street grid layout with 140 duplexes (1977).

At first, the city and surrounding neighbors were picky about the plans, demanding open space, preservation of the trees on the grounds, and nixing the idea of 19-story towers. By the late 1970s, everyone had become antsy to do something. The grading for the first phase of the mixed-use Dorado Terrace development began in 1979.

Now, the complex is about as old as Homewood Terrace was when it closed. While the residences are colorful and provide some welcome housing density in the neighborhood, the Ocean Avenue commercial spaces—cavernous, cave-like, designed for big box retailers who these days aren’t likely to bite—are sad blank walls on the street.

The 24-Hour Fitness keeps chugging along, but the rest has been vacant for… a decade? More? A streetside re-design could only help.

The trustees of Homewood Terrace re-evaluated and moved with the times. Perhaps the ownership of Dorado Terrace should take the hint and do the same.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to Mike D. for doing his part to ensure that I buy you, yes you, a beverage through the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund. We can sip and soliloquize, although it would perhaps be more social to quaff and converse. I have old circus stories and you have that great anecdote I have not heard. Let me know when you are free.

Sources

Julia Scully, Outside Passage: A Memoir of an Alaskan Childhood (New York: Random House, 1998)

Phyllis Helene Mattson, War Orphan in San Francisco: Letters Link a Family Scattered by World War II (Cupertino, CA: Stevens Creek Press, 2005)