Going Down

House-moving in 19th-century San Francisco went in all directions

When Henry Halleck resigned his army commission in 1854, he found ways to stay busy in San Francisco.

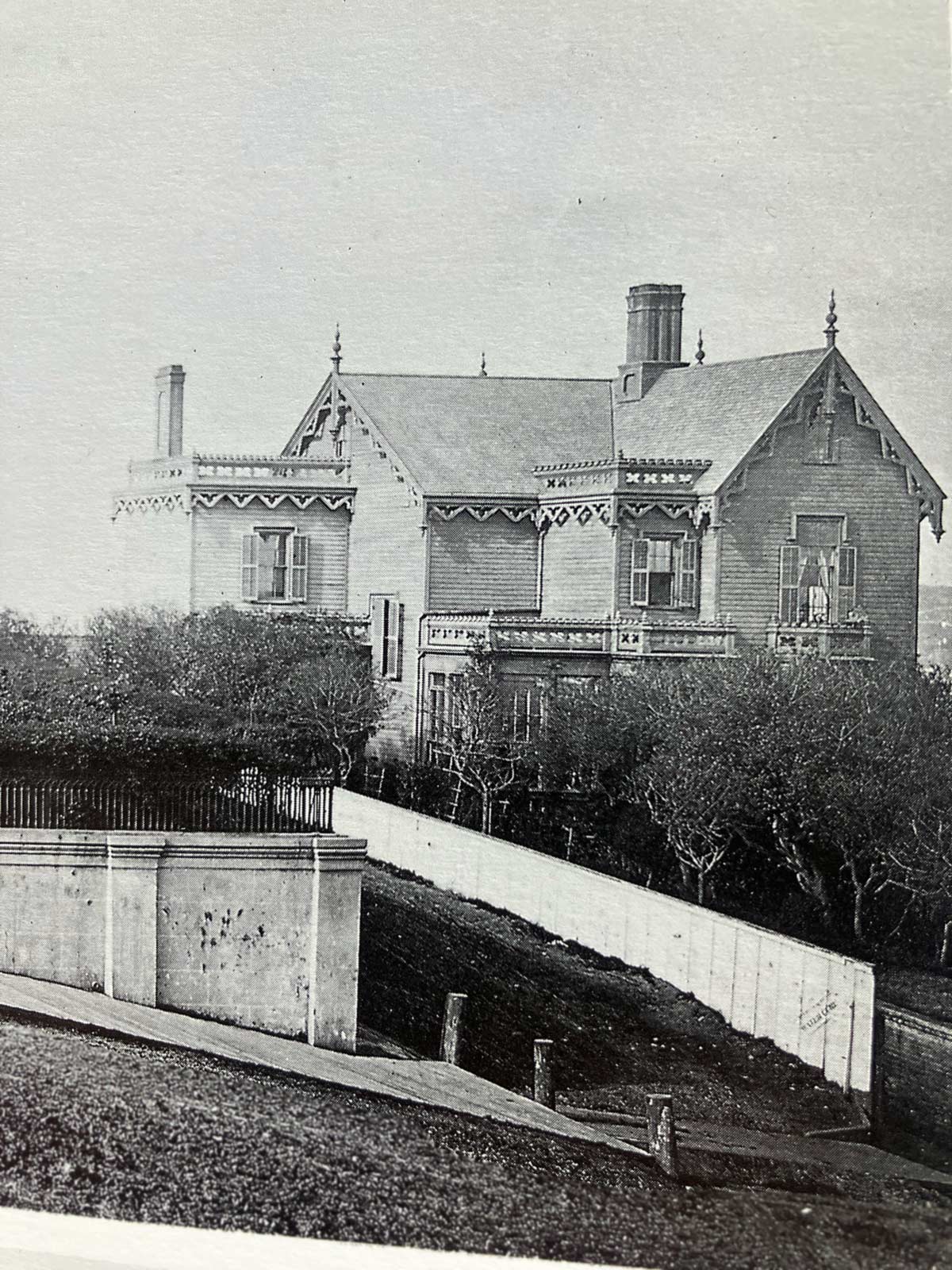

He married a granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton, had a son, formed a law practice, built the new city’s most impressive commercial building, became a director of a bank and a quicksilver mine, headed a railroad company, bought himself a ranch in Marin County, and had the family’s San Francisco residence built at 326 2nd Street on the slopes of fashionable Rincon Hill.

The Civil War changed plans. Halleck returned to the army to serve as General-in-Chief for Abraham Lincoln and the Union Army. After the war, he was assigned back west for a few years and then, in 1869, he was sent to command the Military Division of the South.

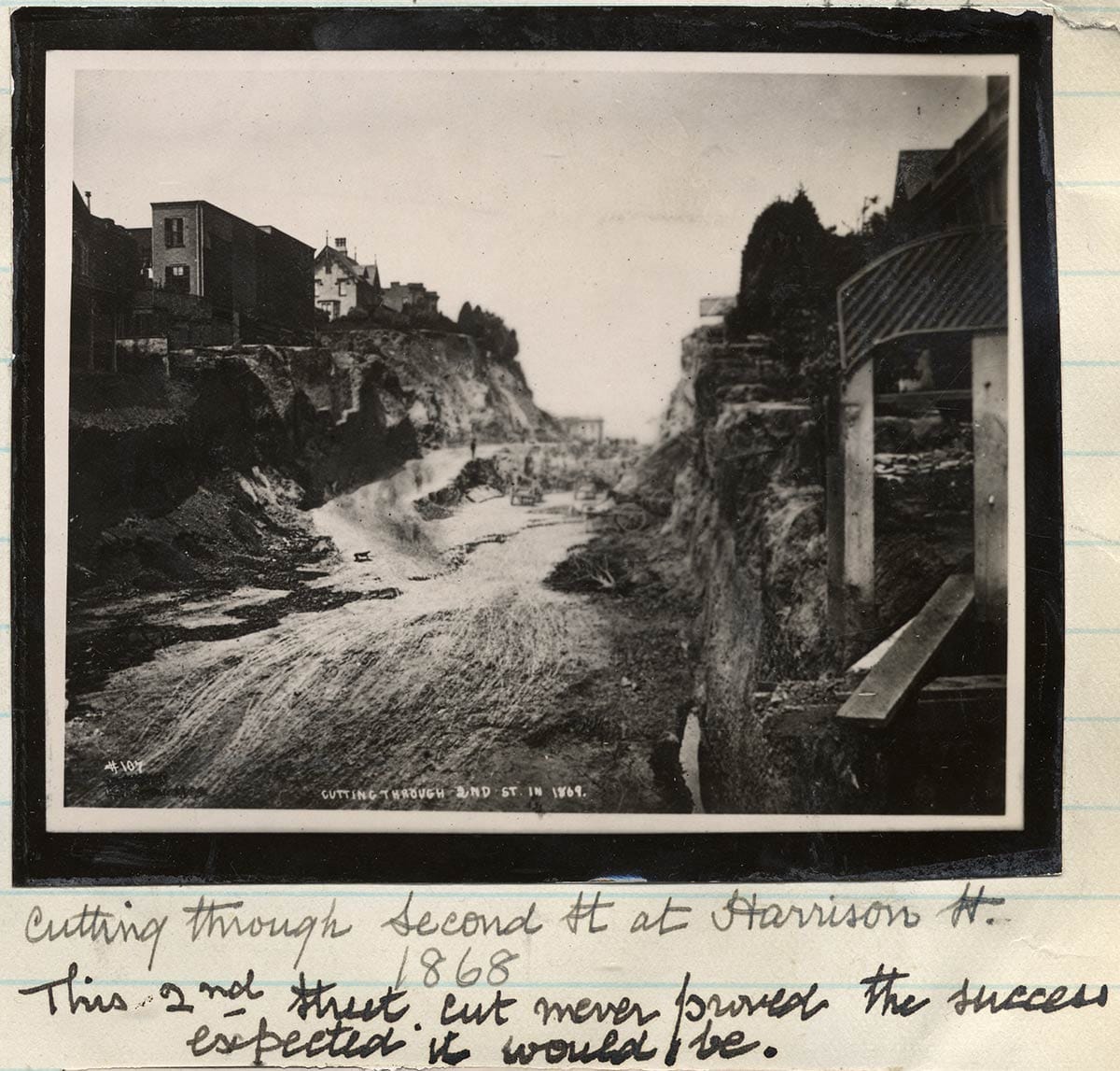

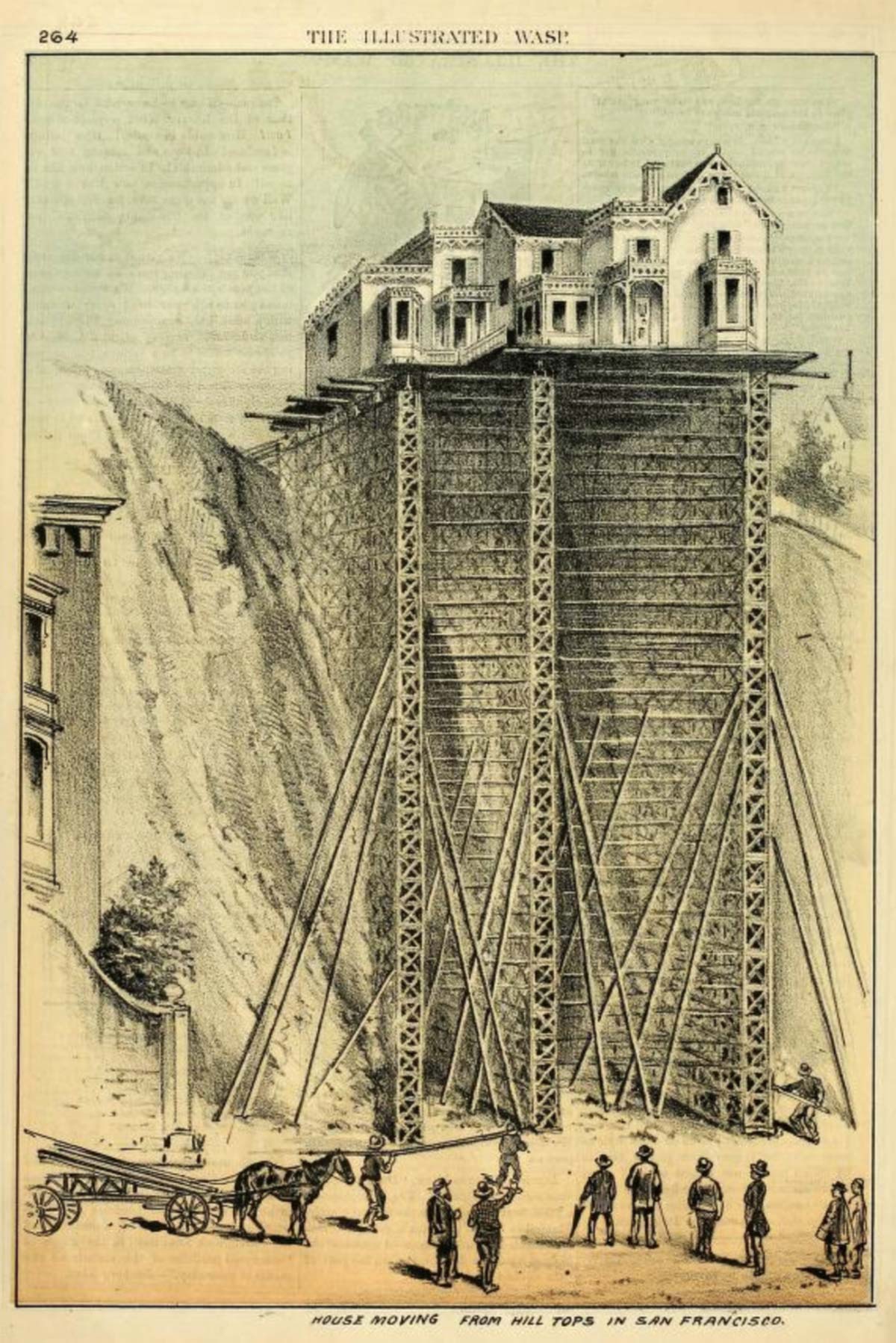

It wasn’t a bad time to leave San Francisco, or at least Rincon Hill. That same year, 2nd Street underwent a little landscaping:

Halleck died in 1872. His widow remarried and did not return to San Francisco, but the family retained the 2nd Street house, now perched inconveniently high above the roadway. In 1878, family representative Colonel George W. Grannis acted to save the home from its Olympian exile by seeking a house mover.

Luckily, it was a field San Francisco was particularly rich in.

On the Move

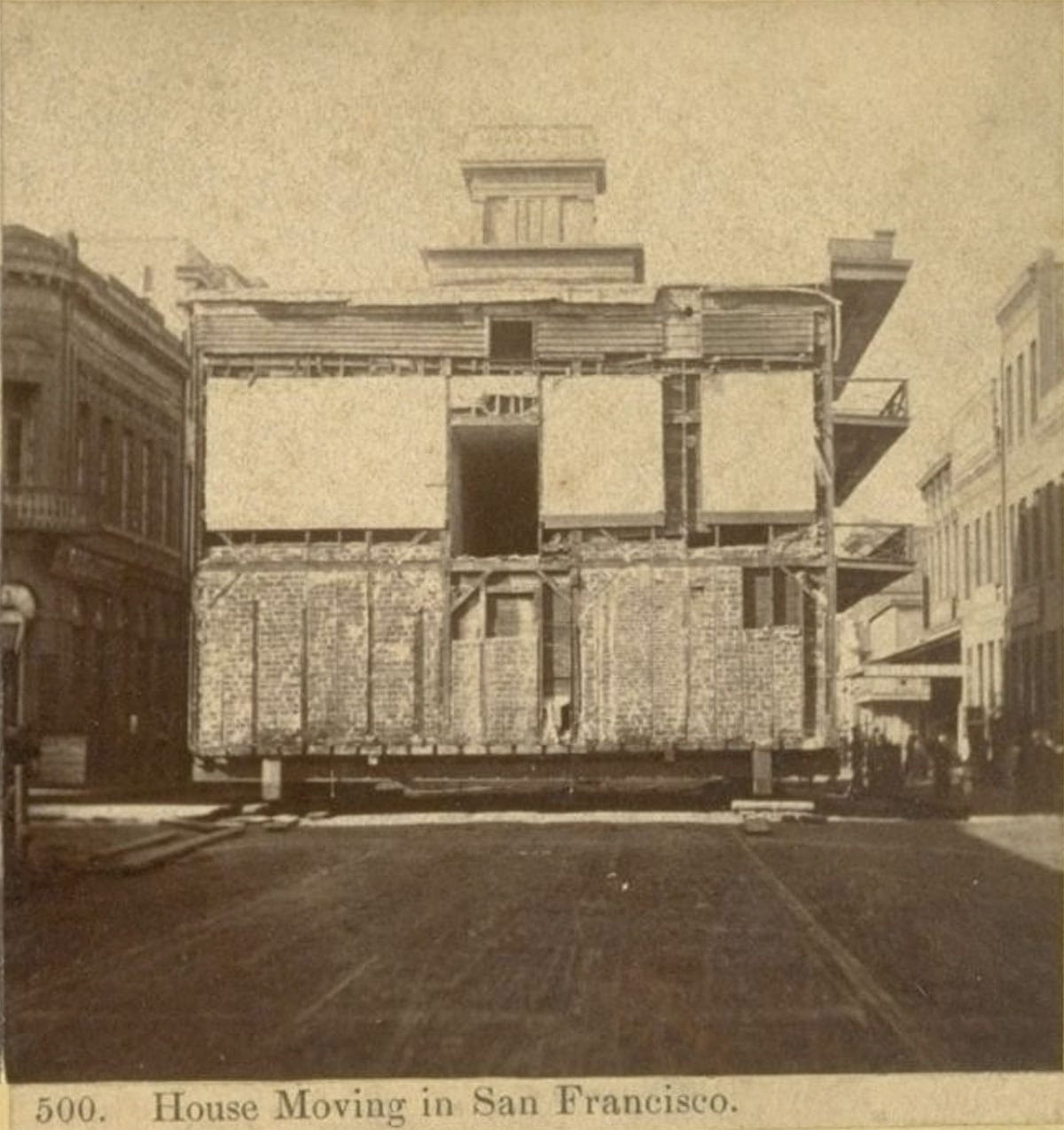

In the second half of the nineteenth century San Francisco was only second to Chicago in a specific and peculiar data point: picking up buildings and hauling them to new locales here, there, and yonder.

The combination of relatively light-weight material as the city’s primary construction material (wood rather than brick) and the dynamic changes constantly underway in a town with a forever-Gold-Rush mentality combined to make the moving of structures a major industry in San Francisco, where more than a dozen contractors specialized in the work.

“[T]he forces of displacement were constantly at work, with larger buildings being built where smaller ones had once stood,” wrote William Kostura in a 1999 journal article on the topic. “The small ones had to be either demolished or moved, and given the economics of the time, these buildings frequently attracted buyers who found it profitable to move and resell them.”

The reasons a building might need to be moved weren’t always to make room for a replacement, but to rescue them from the city’s inexorable infrastructure improvements. The Halleck house, stranded 50 feet above 2nd Street, was a dramatic example.

At first, none of the established contractors Grannis contacted would take the Halleck house job. The distance wasn’t the problem. Using capstans turned by horses and log rollers, San Francisco movers dragged houses slowly to all points of the compass from downtown to the Western Addition, from Nob Hill to Cow Hollow.

Grannis just wanted to relocate the general’s former residence around the corner to a lot on Folsom Street. The issue was the ridiculous drop.

Finally, Colonel Grannis found a less experienced man, Adolphus Tilman Penebsky, who agreed to take the job .

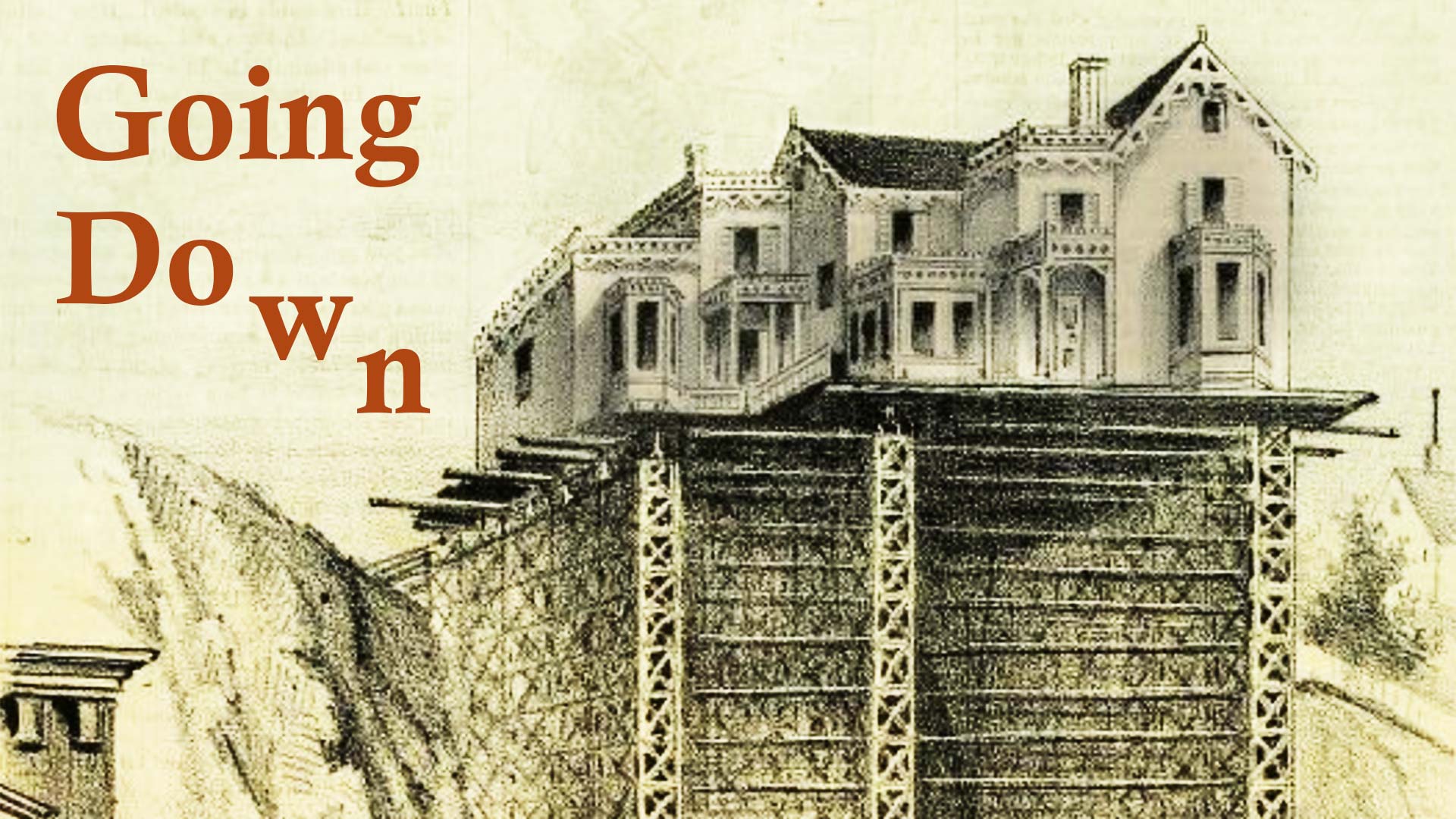

Penebsky decided to rotate the Halleck house, drag it across the hill to the shorter drop on Folsom Street, then slide the building onto a wooden tower constructed on the destination lot. With jack screws set one platform down to lift and support the building, cribbing would be removed level by level from the tower to lower the three-part, 3,700-square-foot edifice to the street.

“Penebsky is a young man, and like young men generally, has the courage to undertake what older house movers consider impossible,” observed the Bulletin, which also pointed out that Penebsky’s contract required the house to be delivered uninjured before any payment was made.

A month after starting the job, Penebsky had the house on the Folsom Street cliff edge, 56 feet above its targeted new foundation. The building reportedly “had a slight tendency to divide,” but was generally intact. Carefully it was pushed out on the tower and in early November 1878 it began to return to earth.

The rate of descent was three feet a day, which the Examiner considered “rapid work.” The paper seemed a little disappointed everything was going so smoothly. “Should [an accident] happen...there would be a terrible crashing by the house on its way to the earth.”

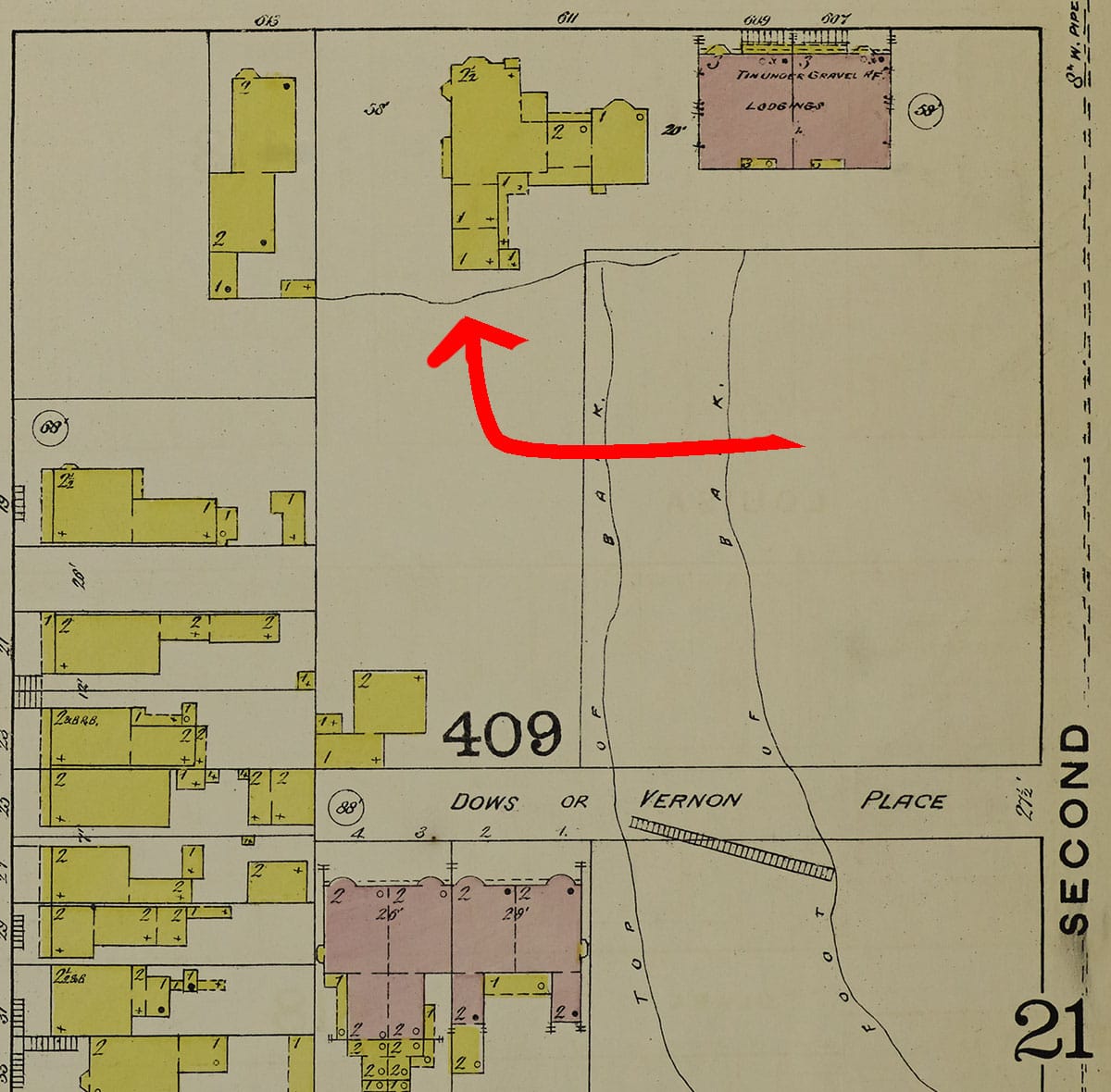

The eagle landed safely and Penebsky got paid. A look at a Sanborn fire insurance map from ten years later helps illustrate the move:

Rincon Hill’s cache was quickly lost after the 2nd Street cut and the refined Halleck residence on Folsom Street soon was neighbor to warehouses, breweries, and rooming houses. By the late 1890s it had been demolished (or moved again?) and replaced by a large Wells Fargo stables building.

The great fires following the 1906 earthquake incinerated fine homes and factories alike and more grading of Rincon Hill further erased signs of Penebsky’s feat.

But the mover himself didn’t trumpet his accomplishment. On the fence of his property in Noe Valley he advertised with a simple sign:

“A. T. Penebsky. Houses Moved and Raised.”

What about houses lowered?

After the Halleck house, perhaps Penebsky decided he was done with those jobs.

Carville talk in the Redwood Room

Speaking of moving... I wrote a whole book on transit cars repurposed at Ocean Beach as residences, bars, and clubhouses—vernacular architecture which was once vehicular architecture.

To the handful of you who haven’t seen my presentation on Carville-by-the-Sea, you can enjoy it for free in the Clift hotel’s Redwood Room next Thursday, February 19 at 6:00 p.m. RSVP here.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to everyone who chips into the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund, one of the city’s most important initiatives in making sure I get out of the house and stop watching old Perry Mason episodes. (“But Mr. Mason, he was already dead when I got there!”) Shout out to Eileen B. for the donation and the nice words this week.

So...the coffee, beer, or wheat grass shot is paid for. When are you free?

Sources

We history people stand on the cribbing of our predecessors. Thanks to Diane Donovan and old friend Bill Kostura for their work on house moving history in San Francisco.

The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, November 23, 1878, pgs. 254, 269.

William Kostura, “Itinerant Houses: A History of San Francisco’s House Moving Industry,” The Argonaut, Spring 1999.

“House Moving Extraordinary,” San Francisco Bulletin, October 28, 1878, pg. 1.

San Francisco Bulletin, November 2, 1878, pg. 4, col. 4.

“House-Moving Feat,” San Francisco Examiner, November 16, 1878, pg 3.

Diane C. Donovan, Images of America: San Francisco Relocated (Charleston, S.C: Arcadia Publishing, 2015)