Jobson’s Folly

In the 1860s, San Francisco's Russian Hill was where one could get above it all thanks to one man's failed scheme.

David Jobson, a native of Philadelphia, arrived in San Francisco in July 1849. He served as a delegate to rewrite the city’s charter in 1853. He became a real estate broker and lived in a house on Powell Street facing a dusty Washington Square Park. He died in San Francisco on August 8, 1876 at 61 years and nine months old.

The only reason he is mentioned or remembered at all in relation to San Francisco history is for an idea he had around 1858. In true Argonaut fashion, he staked a claim, took a risk, and failed with a project some nicknamed “Jobson’s Folly.”

The boom town of San Francisco had six major fires in its first five years of existence. “[T]he fire cry was the call of the dread angel, at whose sound men’s hearts sank, and a whole people mourned,” wrote the authors of The Annals of San Francisco in 1855.

Rather than depend on the call of the dread angel, the city upgraded its emergency alert system with alarm bells. A few of the volunteer fire-fighting companies had belfries and bells by the mid 1850s, but there was also an official city fire bell atop City Hall facing Portsmouth Square.

A city-paid bell ringer alerted the companies to a fire’s location using a simple system of strikes. One ring of the bell was for the First District (between Broadway, Battery, Jackson, and Montgomery Streets), two rings for the Second District (the bay, Montgomery, Jackson and Larkin), etc.

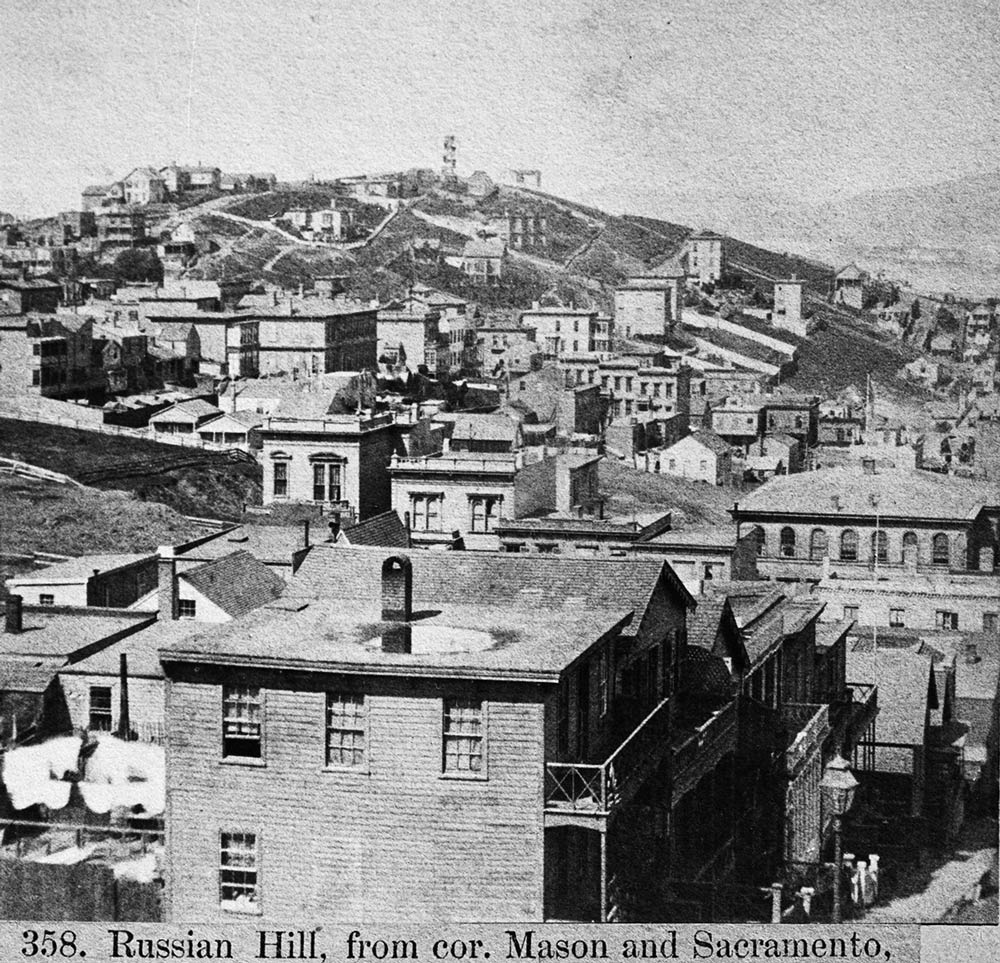

Jobson saw an opportunity to make some money off a square of land he owned at the peak of Russian Hill on the south side of today's 900 block of Green Street. He pitched the location as perfect for a new fire-spotter tower and belfry for the city. He offered to lease the land to the city “for a nominal sum” in 1858. The Fireman’s Journal noted “The position is a commanding one having the whole city in view, and very favorable for sound...”

The city didn’t bite.

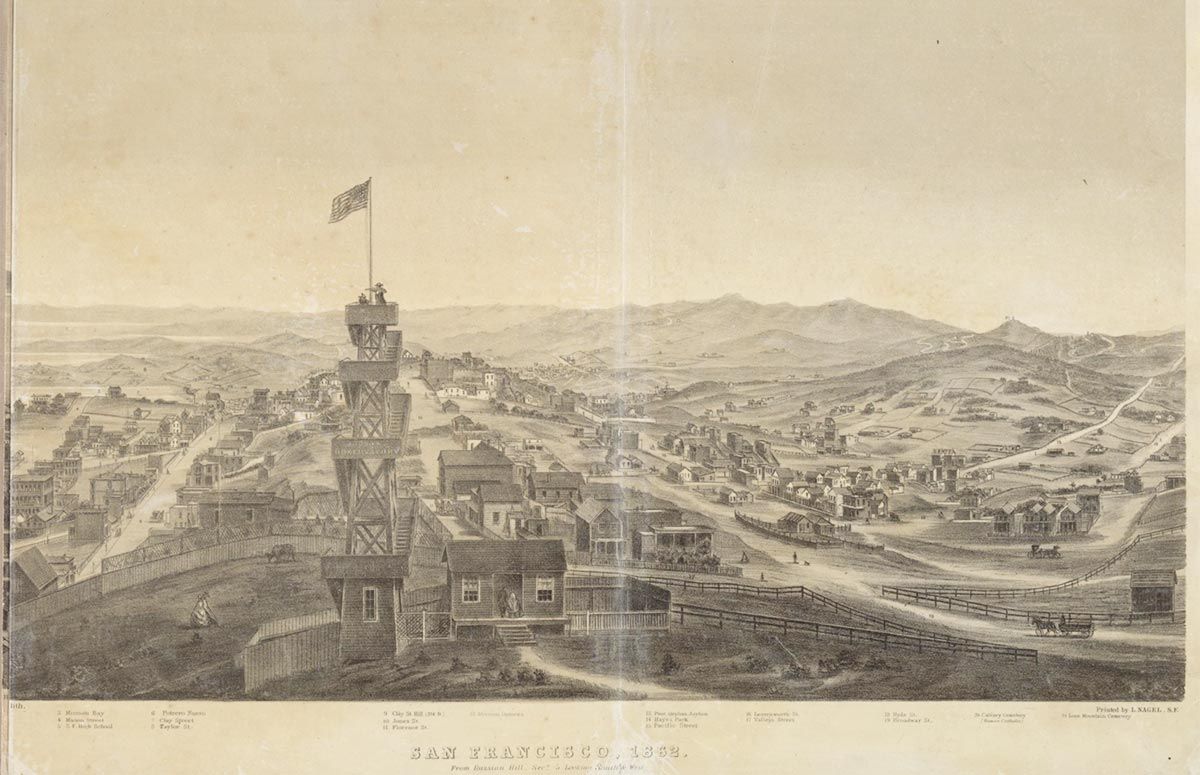

Jobson tried another tack in 1862, building his own 60-foot-tall tower and a small accompanying keeper’s cottage. Once finished, he declared himself “willing to enter into an arrangement with the City Fathers” to have the tower bought or leased for the new fire bell tower.

The city still didn’t bite.

Jobson then ran for district supervisor. The San Francisco Bulletin believed his main objective in doing so was centered on the bell-tower scheme. Because “he had put his foot in it,” […] “if he is elected, the Board may possibly purchase ‘Jobson’s folly.’”

Jobson lost the supervisor’s race handily to A. H. Titcomb and was still stuck with an unused, unwanted fire tower.

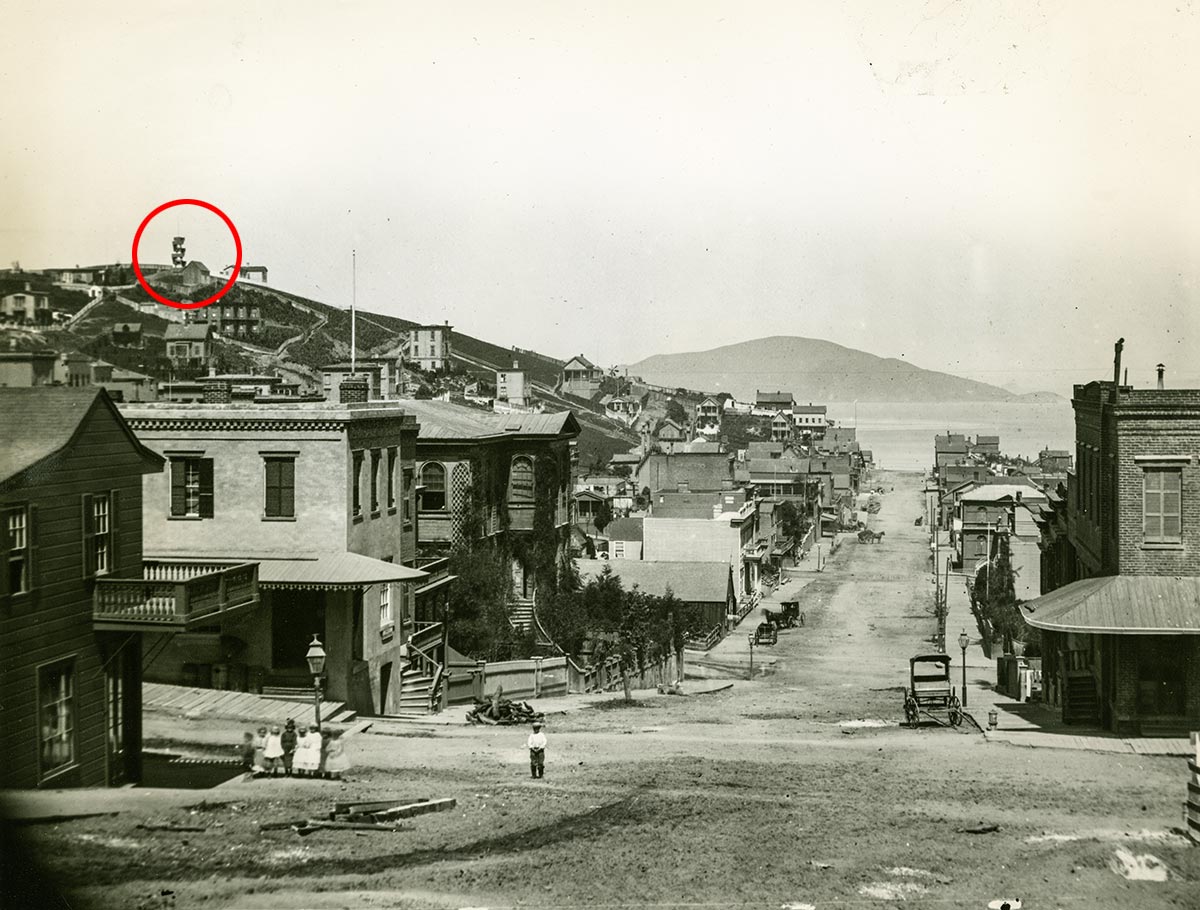

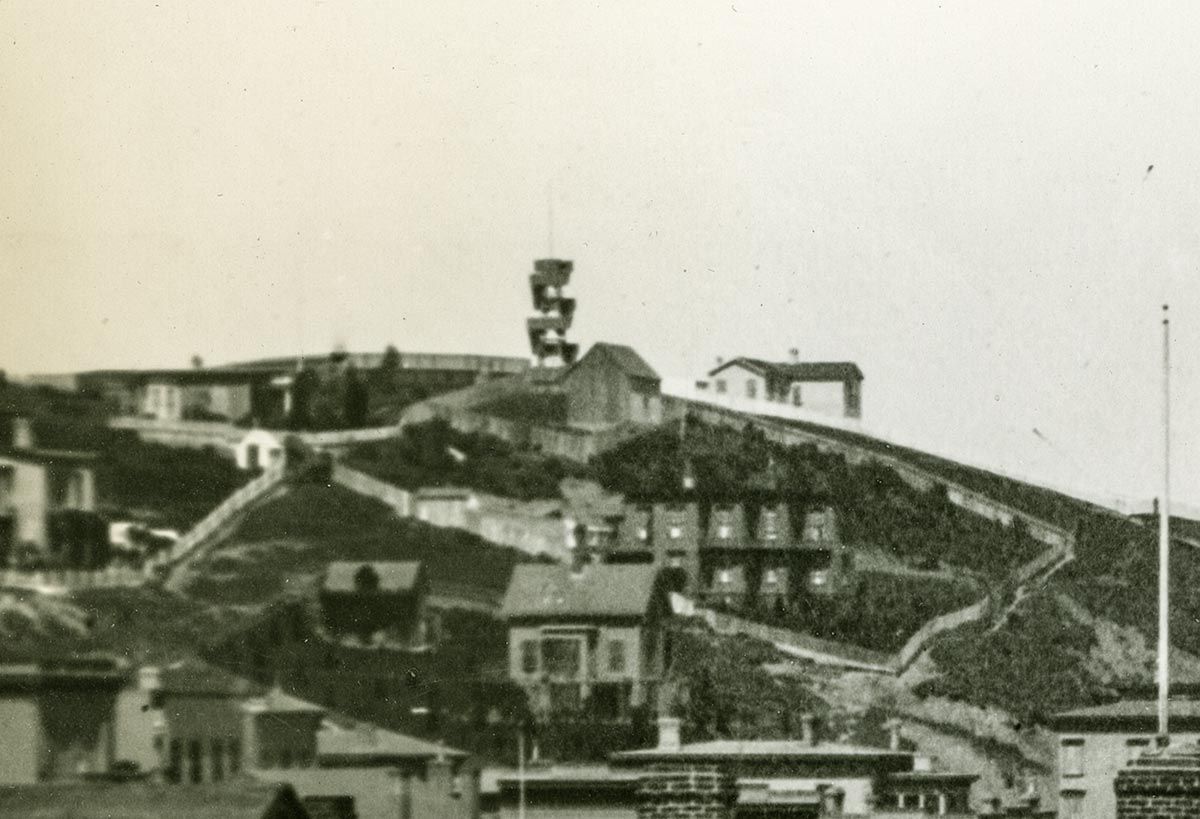

In 1860s photographs, Jobson’s creation is a spirilla cell, a giant spring, an inverted corkscrew on Russian Hill’s summit. It provides a handy reference point for us history-guy-types to put date ranges on historic photos. No doubt some of the early vistas we have of the growing city were taken atop from the observatory.

Up close, it was more of a boxy staircase with a flagpole. One critic remembered it as “a hideous affair, but very serviceable.”

Deprived a government subsidy for his creation, Jobson charged visitors admission—supposedly a dime—to ascend the tower and take in the broad views. It was a business without commercial competition. Under the category of “Observatories” in the 1862 San Francisco City Directory, Jobson owned the only listing.

As with the later Telegraph Hill observatory, people who trudged up to a peak proved obstinate in paying to get a bit higher to look through a telescope. Or they did it once and were done forever.

The observatory’s flagpole received decent use. In April 1862, with the Civil War raging, there was a hubbub when the Union flag was seen flying upside down from the tower: “Some thought the Observatory in distress, others that Russian Hill had seceded; and it was generally believed something dreadful had happened. But their fears were groundless, for it proved to have been the work of some mischief-maker.” Whew.

Perhaps cursed by the restless spirits of the Russian sailors buried on the hill before the Gold Rush (from whom the hill has its name), few things associated with the observatory went right.

Shortly after Jobson built his folly and failed to get city funding, the caretaker died of cancer. Then, to celebrate Cinco de Mayo in 1865, a contingent of the city’s “patriotic Mexican residents” raised a Mexican flag at Jobson’s observatory and somehow dragged a small cannon up for a 21-gun salute at sunrise. They got about half-way through the exercise when the overheated gun exploded. “[W]e regret to say,” reported the Daily Alta, “that four men were more or less seriously injured.”

The observatory escaped undamaged, however, and was still standing in 1867 when Jobson put his property on the market. It disappeared from photographic record shortly thereafter.

Today the site is occupied by two 1920s apartment towers. Those views will cost you more than a dime.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

I’ve been catching up on my Woody Beer and Coffee dates and my wife says I’m more social than Rona Barrett. (She didn't really say that, but Rona emerged like Athena from the deepest crevice of my 1970s pop culture mind. In our unsettled social media landscape I would fully support a “Rona” app.) Great thanks to Nik D. (F.O.W.), Matthew S., and Doug S. for their donations this week! Is it time for your round?

Sources

Frank Soulé, John H. Gihon, James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco (San Francisco: D. Appleton & Co., 1855), pg. 614.

“Bell Tower,” Daily Alta California, March 9, 1858, pg. 1.

“Fire Tower and Observatory,” Daily Alta California, February 12, 1862, pg. 2.

“The New Observatory,” Daily Alta California, February 18, 1862, pg. 2.

“A Panic on the Hill,” San Francisco Bulletin, April 10, 1862, pg. 3.

“Mongrel Candidates for District Offices,” San Francisco Bulletin, May 17, 1862, pg. 3.

“Celebration of the Mexican Victory of La Puebla,” Daily Alta California, May 6, 1865, pg. 1.

“Real Estate,” Daily Alta California, July 29, 1866, pg. 1.

“Haunted Houses,” Daily Alta California, February 18, 1889, pg. 1.

“Some of Our Deacons’ Follies,” San Francisco Call, May 31, 1893, pg. 10.