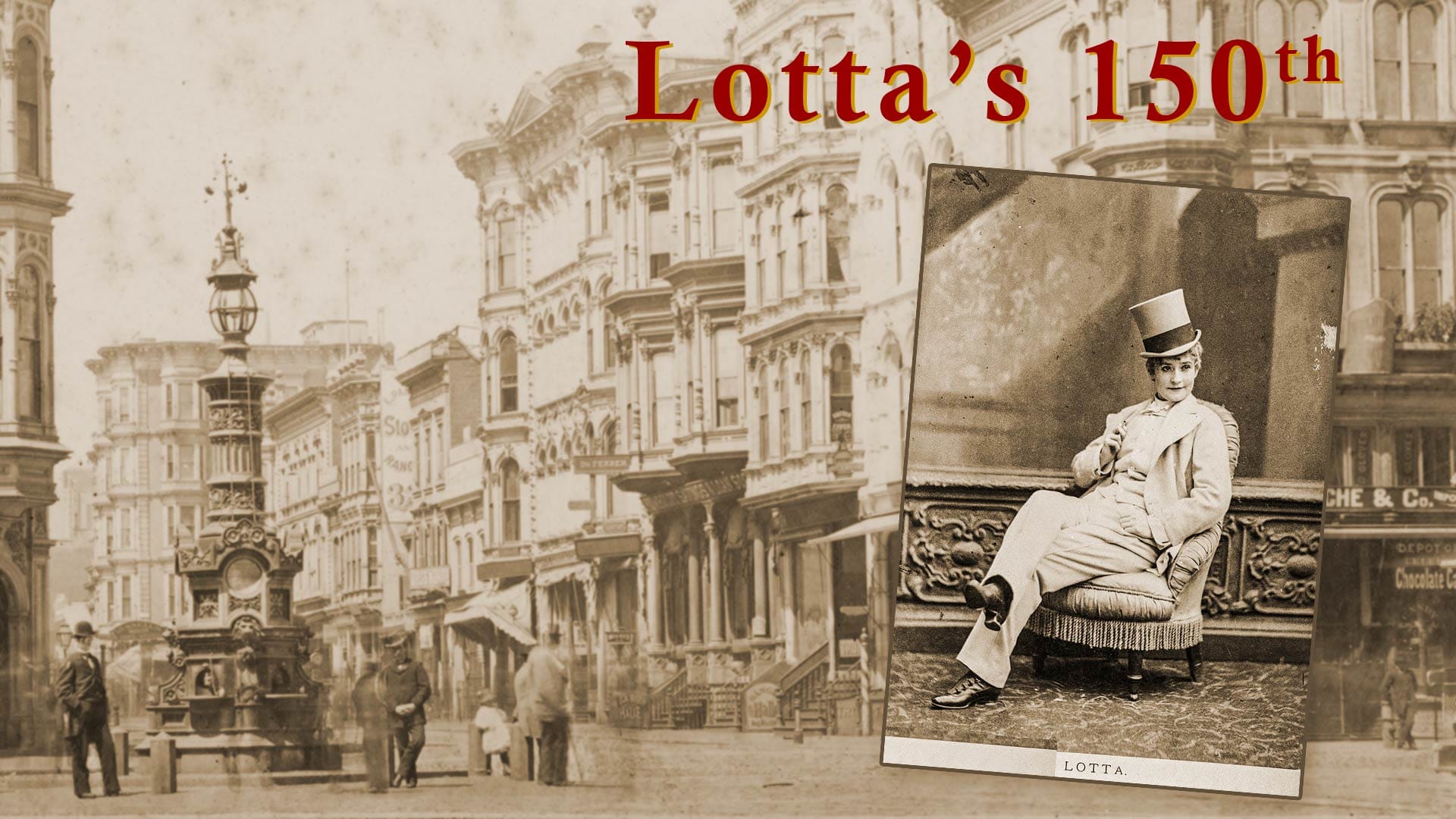

Lotta’s 150th

A birthday for San Francisco's most liked landmark.

Tuesday, September 9, 2025, will represent the 150th anniversary of Lotta’s Fountain, a public monument determined in a recent survey to be the most liked in San Francisco’s civic collection.

There are good reasons.

The darned thing is older than anyone alive, a real achievement in San Francisco, where historically our official city policy is “open season on anything that didn’t get incinerated in the 1906 fires.” (Progress, you know, can’t stop change, need to attract people who don’t live here to spur the economy, etc, etc.)

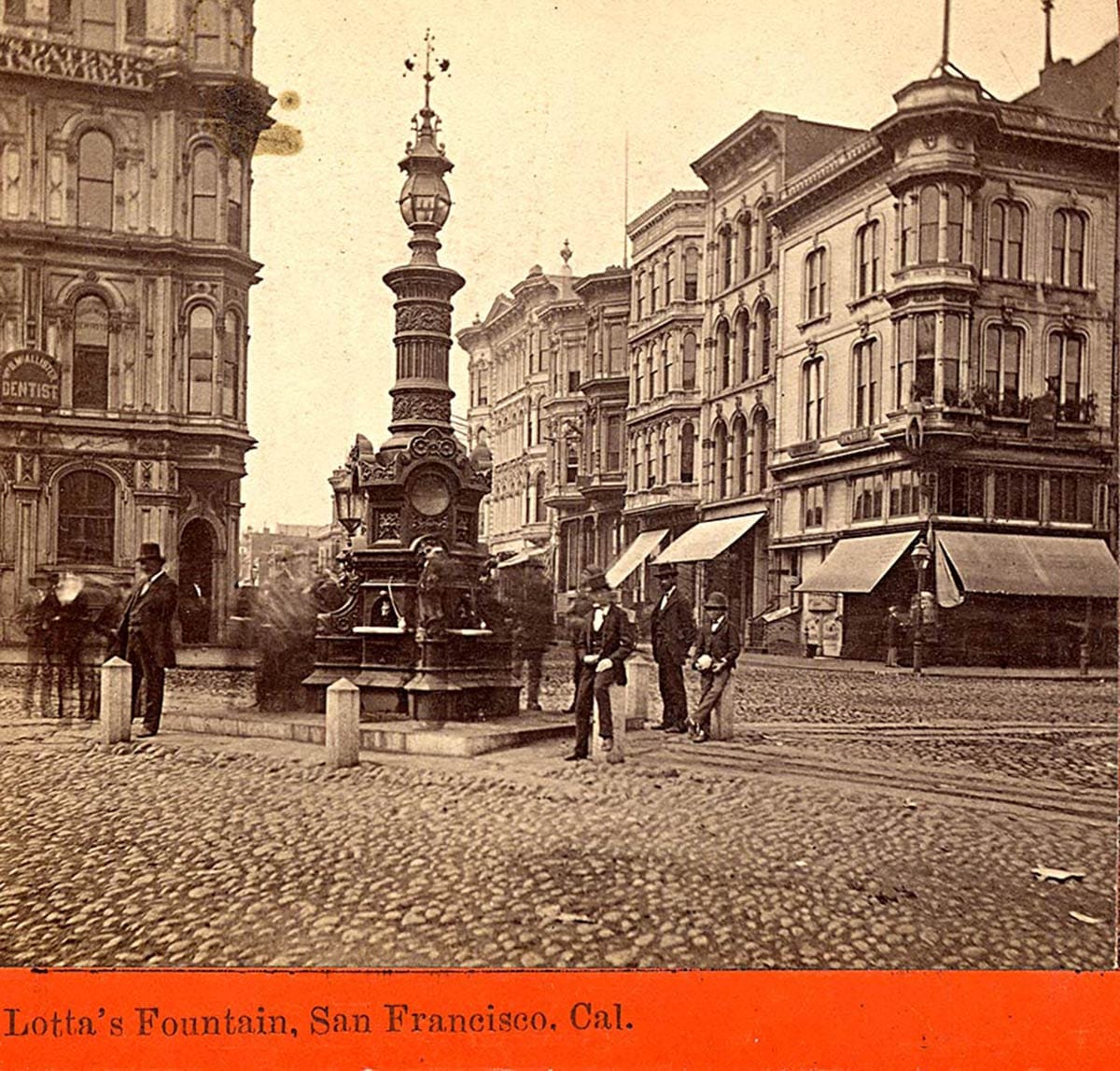

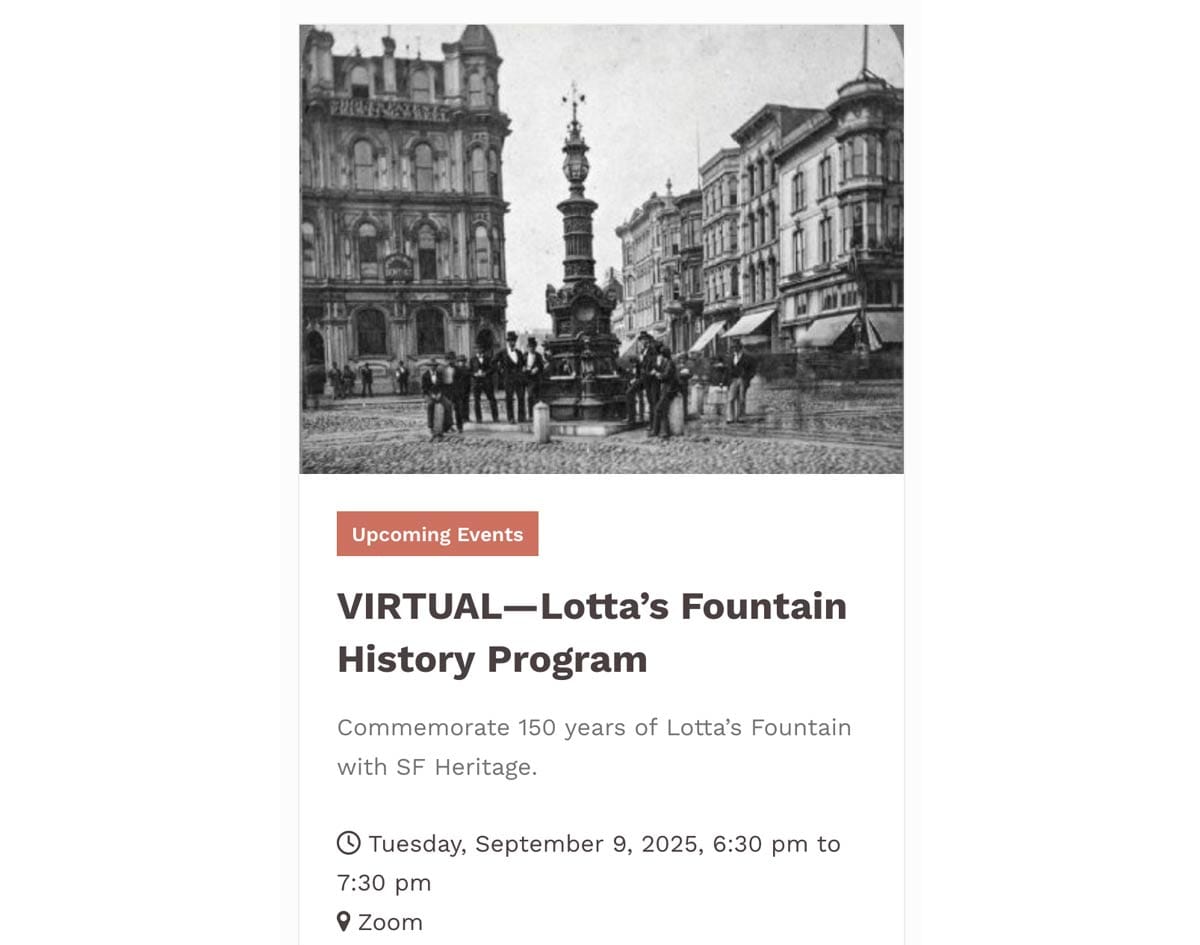

The fountain is also prominent and well known. Other San Francisco monuments and statues have been shuffled around, some multiple times. While it was moved slightly and had a strange alteration in 1916, Lotta’s Fountain has been essentially in the same place at the intersection of Market, Kearny, and Geary streets, a historical confluence of foot and vehicle traffic.

Monuments are a flash point in public conversation these days, but whereas even Abraham Lincoln is now getting the side-eye, most people give Lotta’s Fountain a pass. Yes, there are some inserted scenes of Gold Rush miners and clipper ships representing a migration/invasion with disastrous effects on Native Americans, some Californios, and the environment, but they are almost afterthoughts in the fountain design which seems to be going for “model of a lighthouse designed by Belle Époque Parisians.”

Oh, and it has lion heads, which people generally like.

Even if you don’t care for gilded leonine-studded shafts, it’s hard to hate Lotta’s Fountain. San Francisco Heritage conducted a historical survey of downtown in the late 1970s and one reviewer summed up his appraisal as “Ugly, but we love it anyway.”

Lotta

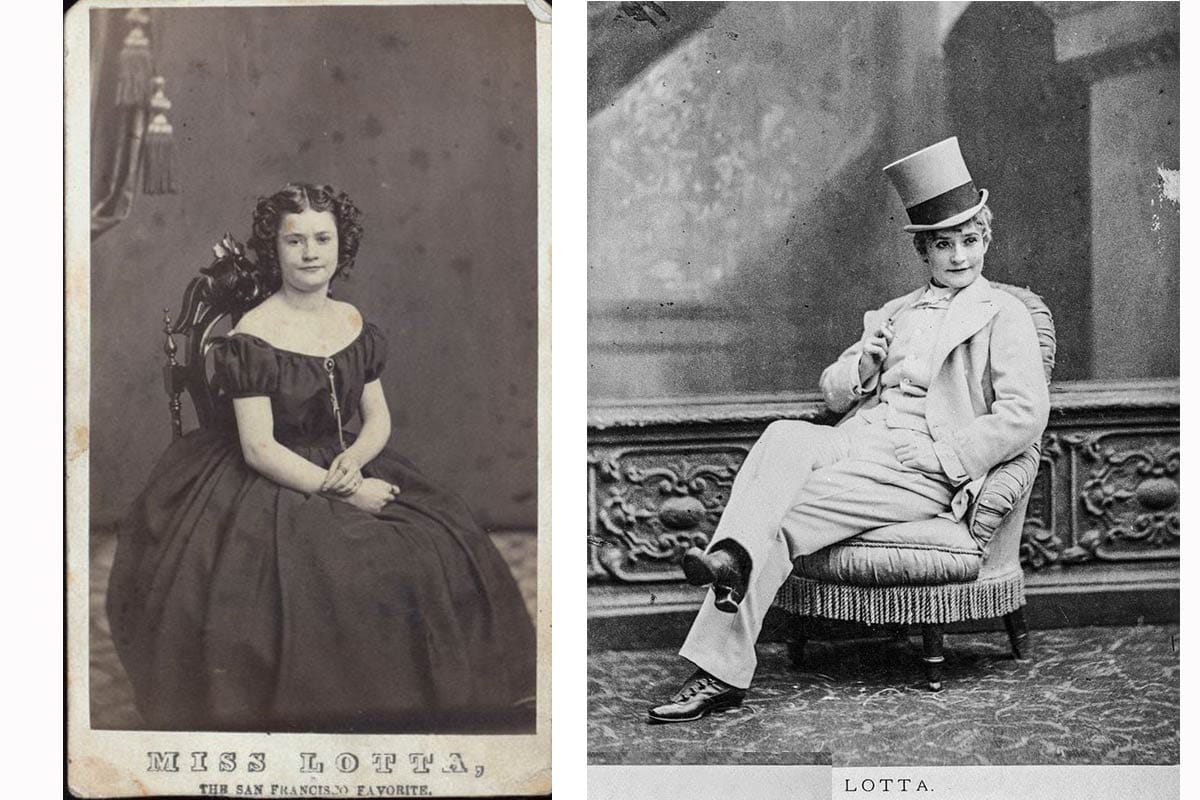

There are parallels here to explore about loving something despite one or more logical objections. Actress Lotta Crabtree gifted the fountain to the city. Over her entire career, critics said she wasn’t the greatest or most graceful actress, nor the most able comedienne, dancer, or singer, nor the most beautiful. But almost all loved her or at least recognized that audiences did.

From her time as a child “fairy star” performing for rough crowds in remote Gold Rush camps to her multiple runs in Broadway productions, Lotta Crabtree owned the stage and could get any crowd on her side. You can feel her charisma in old photographs and across a range of roles: mischievous imp, deadpan impersonator, kittenish ingenue, star-crossed heroine, arch matron...

She couldn’t be resisted. She was Lotta. No need for the surname. Everyone knew who you meant.

No one is a saint, but Lotta’s ability to win just about everyone over and her somewhat reclusive nature off-stage kept her reputation relatively clean in her lifetime. But from our Olympian present-day perspective, our 21st century lens, we can find faults with Lotta.

Minstrel shows and ethic humor were the backbone of popular entertainment when she started singing and dancing her way into people’s hearts. We would not be happy today seeing Lotta in blackface playing Topsy from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Lotta prancing through her “Irishman jig” routine, or Lotta plucking banjo in hoe-down numbers and using “dem” and “dos” vernacular.

We would not like that at all.

But her early minstrelsy did not define Lotta Crabtree’s career or personality, it was subordinate to her legacy perhaps in the same way the Gold Rush plaques are to the fountain as a whole.

Lotta also gets points in that the fountain wasn’t erected in her honor. Her donation is recognized upon it, but the actress seemed careful not to have the gift seen as a monument to herself. She didn’t even come to the dedication. She didn’t call it Lotta’s Fountain, we do.

The gift wasn’t meant to be purely decorative but of utility. The fountain’s light was a beacon in an era of dark intersections. The fountain’s basins originally had tin cups on chains. The provision of accessible drinking water, not a given in all parts of the city, not in many parts of the world today, was rightfully considered a generous public benefit in the nineteenth century.

At the unveiling ceremony in 1875, held on the 25th anniversary of California’s admission to the United States, a reporter archly noted that the crowd “consisted largely of idle hoodlums, to whom it was apparent that water would be a precious boon…” Lotta’s aunt, Mrs. Vernon, no doubt excluded from the reporter’s label of hoodlumhood, took the first draught from the fountain.

Survivor

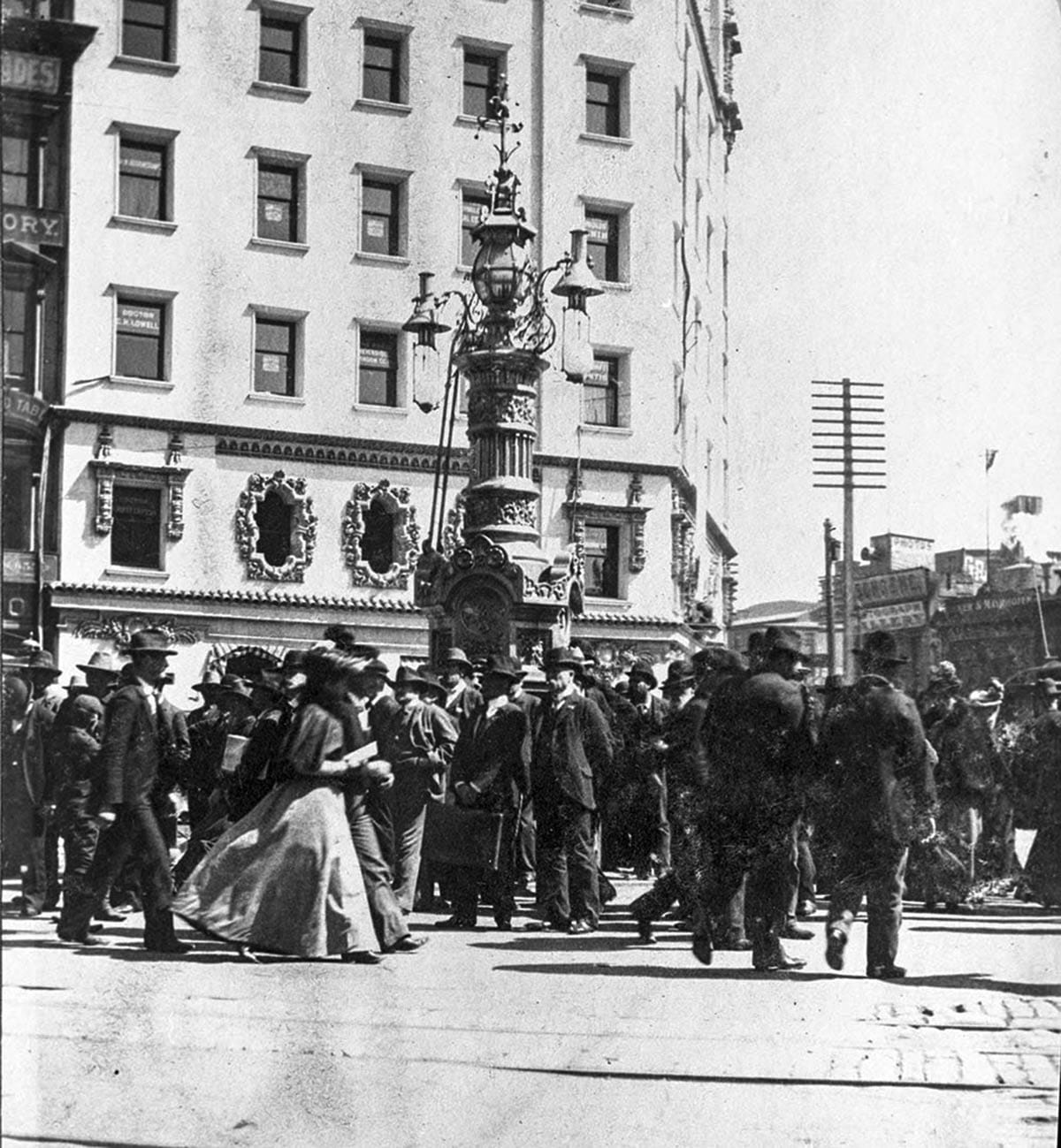

Lotta’s Fountain got through the 1906 earthquake and fire as the city’s prestigious hotels, new office towers, department stores, and newspaper buildings burned all around it. Refugees set trunks and furniture about the mid-intersection shaft during their escapes from the flames.

After the ashes cooled, the fountain was a meeting place for those separated during the disaster. For survivors, and now for those remembering the survivors, Lotta’s Fountain became the early-morning gathering spot on each anniversary of the April 18, 1906 earthquake.

Somehow more surprising, the fountain has survived generations of people brushing against it, climbing on it for parades and concerts, crowding it with power poles and traffic signals, covering it with promotional structures, and newsboys, traffic cops, and lunchtime idlers like me leaning upon it.

It even survived being improved.

In 1916, as San Francisco began extending the installation of its grand “Path of Gold” light standards along Market Street, the shabby state of Lotta’s Fountain became a theme of letters to the editor of the San Francisco Chronicle.

In January 1917, artist and park commissioner M. Earl Cummings submitted a plan to the Board of Public Works to create a new traffic island around the fountain and insert a tall shaft so the fountain matched the height of the new streetlights. It would also get a new coat of paint.

A few months later, it was done. Letter-writers now complained it was desecrated and the city’s favorite daughter had to be insulted. (Crabtree, ever above such debates and living on the East Coast, apparently gave her approval for the modification.)

The super-sized version lasted until 1998, when a windstorm damaged the shaft. A restoration effort brought the landmark back to its original height. The fountain supposedly is once again able to run, although I can’t say I have ever seen a drop of water come out of it in my lifetime.

Commemoration

On September 9, 1875, one of the speakers at the dedication ceremony predicted “the solid iron fabric must last and survive the ruins of centuries and the name of the kind-hearted little actress will long be upon the lips of those who will in the far distant future experience the benefit of her thoughtful deed.”

There are no official plans to mark the day of the 150th anniversary. Tuesdays are hard for city officials. The Board of Supervisors may issue a commendation. The Arts Commission is working on a big to-do event to mark the occasion later in the year. I will keep you posted.

But we should do something for the actual day. My staff and I at SF Heritage will drop by about noon with some flowers. Maybe a few history friends will join us. That night we are putting on a virtual online program on the history and legacy of Lotta’s Fountain. Can you join us? It’s free.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to J. B., who donated to the fund that keeps Woody and his friends dehydrated, as I believe beer and coffee do. Better mix in some big glasses of water... Are you free to let me buy you a drink? We can talk about 21 transfers and that night at the Mabuhay Gardens. Let me know.

Sources

“Lotta’s Fountain,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 10, 1875, pg. 3.

San Francisco Monuments and Memorials Advisory Committee, Final Report, May 2023.

Lawrence Estavan, Ed., San Francisco Theatre Research, Monographs, Vol. 6, First Series, WPA Project 8385, October 1938.