Tetrazzini's Christmas Gift

In 1910, the world's greatest soprano gave San Francisco a present.

Luisa Tetrazzini, the most famous coloratura soprano in the world, was not going to back down.

Impresario William “Doc” Leahy had her booked to begin an extensive 1910 tour of the Americas. It would kick off in San Francisco, the city where she had made her United States debut five years earlier.

That 1905 run at the Tivoli theater had pushed the career of the vivacious opera star to its great heights. From her runaway success in San Francisco, she had gone on to New York and London, where at one performance at Covent Garden she received 20 curtain calls.

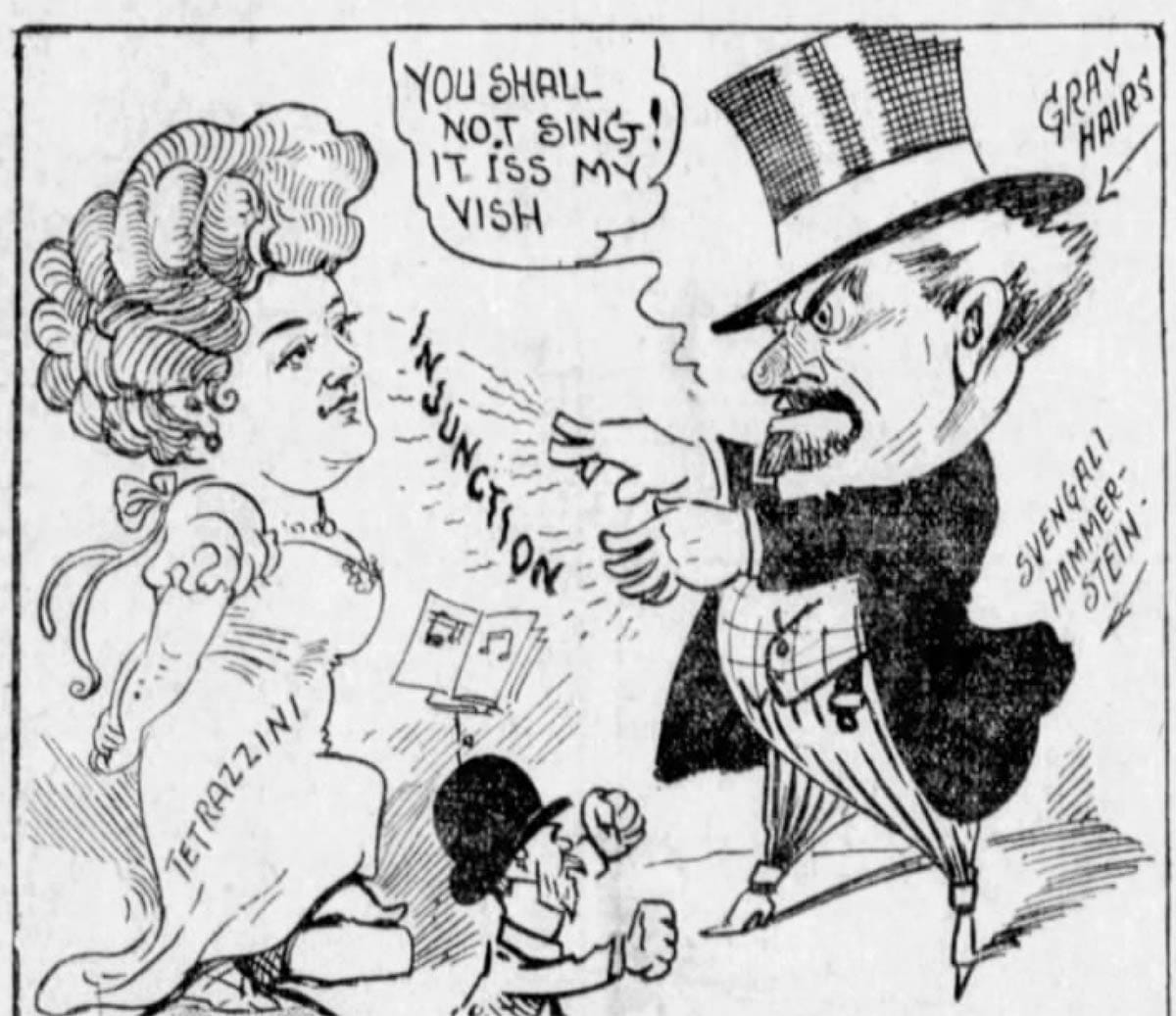

But just as her 1910 tour was about to begin, while Tetrazzini steamed across the Atlantic on the Cunard liner Mauretania, New York theater owner and promoter Oscar Hammerstein prepared to thwart her.

Hammerstein—grandfather to the lyricist and librettist you know from Rodgers and Hammerstein musical fame—claimed he held an option in a older contract to book Luisa Tetrazzini in the United States. It was only he who could decide when and where in America she hit her high C’s.

On November 24, 1910, just as her liner reached New York harbor, the prima donna was served injunction papers by a deputy U.S. marshal in her stateroom. Tetrazzini’s lawyers would be required to prove she wasn’t under Hammerstein’s control and, tied up in the courts, it seemed she would miss her booked December dates in San Francisco.

Petting her chihuahua, “Aurora Borealis,” a defiant Tetrazzini gave reporters a tasty quote:

“I will sing in San Francisco. I will sing for nothing in that city, where I was so warmly welcomed when I first came to America. If necessary, I will sing in the streets. I will sing at Lotta’s Fountain and let those who would hear me stand in the street. It will all be free. The Courts cannot prevent that, can they? No. Well, it will be done.”

A Promise Fulfilled

On December 5, 1910, the presiding judge essentially cut a deal. Leahy and Tetrazzini could continue on their planned tour if half of her earnings were deposited in a trust while a final decision was made on Hammerstein’s claim.

Leahy was paying her 40% more than Hammerstein’s old contract. The parties would eventually settle in July 1911, with Hammerstein receiving about half the difference, but in December 1910, the soprano and San Franciscans chose to see the judge’s preliminary decision as a complete victory for Tetrazzini and the city by the bay.

San Francisco still had a bit of an inferiority complex, sensitive that the rest of the world viewed it as a rough frontier town and cultural backwater. Any validation of the city’s preferred identity as “Paris of the West” was eagerly seized upon, especially as it rebuilt from the 1906 earthquake and fire.

Tetrazzini’s return, already much anticipated, was now viewed as a historical moment for the city: because of her love for San Francisco, opera’s grandest diva would gladly sing for free in the streets.

Advance tickets for the rescheduled concerts sold out quickly at ticket prices ranging from $3 (a bit over $100 in 2025 dollars) to $1.50 on the lower floor of the Dreamland Auditorium in the Western Addition. (All the downtown houses were still being rebuilt after the 1906 disaster.)

Shows were added. They also sold out. The city quivered with expectancy. The Examiner published a breathless article just on the early arrival of Tetrazzini’s luggage.

The singer, her husband, Doc Leahy, and Aurora Borealis (which newspapers frequently claimed was “the smallest Mexican hairless dog in the world”) arrived on December 9, 1910. Reporters described Tetrazzini as radiant, as “chattering on with the unaffected joy of a child” because of her enthusiasm to sing in San Francisco.

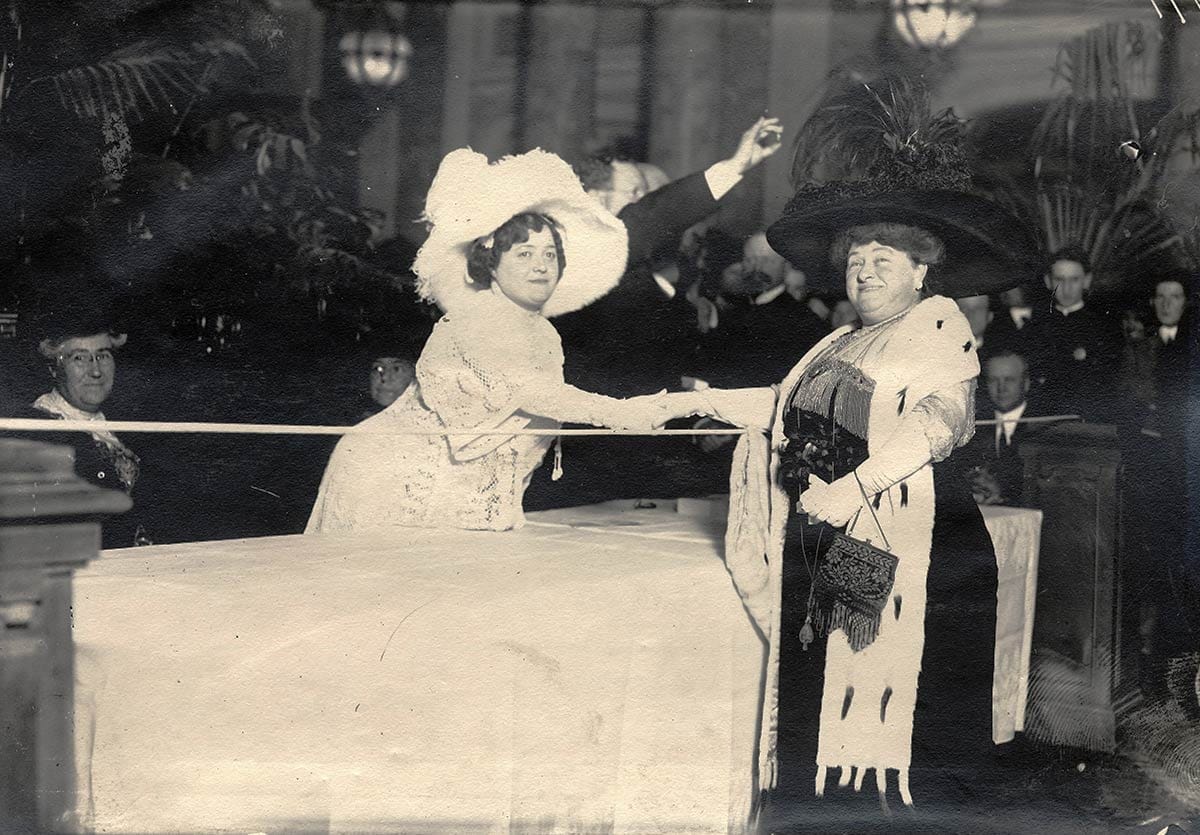

The party stayed at the Palace Hotel, in whose palm garden Tetrazzini promised to appear for a Red Cross fund-raising drive hosted by prominent society women. Leahy secured a commendatory telegram from President Taft for the act, which was dutifully reprinted by the press.

It was good publicity for his singer, but ahead of her nationwide tour the manager had something better up his sleeve.

On December 21, 1910, it was announced that Madame Tetrazzini would fulfill the promise she made in New York. The greatest coloratura soprano in the world would risk her rare money-making voice by singing outside, at night, for free, at Lotta’s Fountain.

The event would take place on Christmas Eve as a gift to the city.

“San Francisco is My Country”

The Chronicle, whose offices stood right across from Lotta’s Fountain, tried to take all the credit, but every daily put the news on their front pages and Tetrazzini said it had all been her idea in New York.

“I want the people to know that I have not forgotten San Francisco wherever I have been. When they asked me in Europe what city I liked the best I always told them ‘San Francisco.’ […] I like San Francisco better than every city in the world. San Francisco is my country.”

A stage was hastily constructed by the Public Works department. A children’s choir was booked as an opener. The young voices would do a number of Christmas carols. There were lively conjectures of what Tetrazzini would sing.

Special trains were arranged to bring music lovers from San Jose, Sacramento, and Stockton for the concert. Predictions of 10,000 possible attendees rose quickly to 100,000, then 200,000.

The United Railroads company graciously complied with the mayor’s request to divert streetcar lines during the event. Not that they would have been able to get anything through the intersection of 3rd and Market streets when the evening came.

There was no amplification system, but a reported 250,000 filled the blocks up to Union Square in hopes of hearing Tetrazzini’s golden notes. (Let’s not get too attached to that number and say there were lots of people.)

The entire city seemed to be there: “bootblacks rubbed elbows with bankers, and painted creatures with the fat and wholesome mothers of families.”

The windows, ledges, and roofs of every surrounding building were thick with hopeful listeners. Office workers hung phone receivers outside so their families could hear the concert at home. A reporter counted 568 guests filling the windows of the Palace Hotel.

The City of Paris building, two blocks away and facing the wrong direction for the sound, was “crowded with people who strained far out to catch the faintest echo of the wonderful voice in order that they might afterward tell their children and grandchildren that they participated in the wonderful event when a whole city turned out in the streets on Christmas eve to listen to a song.”

The Call’s music critic perched himself high up on a ledge of the newspaper’s headquarters on the southwest corner of 3rd and Market streets. He tried to listen to the carols of the opening choir and the faint strains of the small orchestra over the crowd buzz. He couldn’t pick out a word of the mayor’s speech. As Tetrazzini was introduced to the stage to thunderous applause, the critic wondered whether he’d be able to hear her at all.

“Then she sang.”

The immediate rapt silence of tens of thousands of people huddled together under a clear winter night sky awed every chronicler of the event. An individual shifting his feet on the street could be heard a hundred yards away.

The great soprano, in a salmon-pink cloak, an iridescent white gown of 3,000 rhinestones, and a prodigious white ostrich-feathered hat, sang just two songs: a sentimental classic, The Last Rose of Summer, and the joyful waltz from Gounod’s opera, Romeo and Juliet.

The Call critic on his ledge was amazed. “[H]er song was upborne on wings and floated, free, untrammeled and lovely to the extreme verge of the silent crowd.”

“Every intaken breath was a caress; every exhaled sigh was a prayer,” gushed the spellbound critic from the Chronicle. “[E]ach upraised hand was a benediction; every tintinnabulating scale of molten notes was a hallelujah.”

Men in the audience cried. Some of the orchestra musicians cried. A child was heard to make a wondering gasp at one of the high parts.

When Tetrazzini’s last note faded, the crystal stillness snapped, and the crowd erupted. “It was a hurricane of love, blown by the winds of affection.”

The orchestra took up Auld Lang Syne. The beaming diva, tears in her own eyes, waving, smiling, as she was escorted away, joined in with the tens of thousands of voices. She told a reporter in French, “Please, please tell San Francisco that I thank it—thank it from the very bottom of my heart—and that I am happier tonight than I have ever been. Oh, I love San Francisco, for it is my home.”

The next day, Christmas Day, the concert was reported in newspapers from Seattle to Baltimore, Los Angeles to Puerto Rico. The New York Times put it on its front page.

San Francisco’s four daily newspapers, competitive rivals and split in opinion on almost any subject, were, for once, united: this had been the greatest night in the city’s history. They even ventured it could be called the greatest night in music history.

Woody Yule Ale and Mulled Wine Fund

You do not have to contribute to the make-Woody-get-out-and-be-sociable beverage fund to take advantage of its benefits. You have to do something much more difficult: find space on your calendar to meet me! I will take care of the rest. Let us figure this out and have a coffee, beer, or fermented something together.

Merry, merry.

Sources

“Tetrazzini Here; Meets Injunction,” New York Times, November 25, 1910, pg. 11.

“‘I’ll Sing in Streets,’ Says Luisa Tetrazzini,” Sacramento Bee, November 26, 1910, pg 15.

“Awaiting Tetrazzini,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 27, 1910, pg. 23.

“Tetrazzini Wins; Starts West,” San Francisco Examiner, December 6, 1910, pg. 1.

“Eight Trunks Herald Tetrazzini’s Coming,” San Francisco Examiner, December 9, 1910, pg. 9.

“Tetrazzini, All Smiles and Gayety,” San Francisco Call, December 10, 1910, pg. 3.

“Tetrazzini Will Assist in Sale of Xmas Stamps,” San Francisco Bulletin, December 17, 1910, pg. 10.

“Here is my Country, Diva Says,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 21, 1910, pg. 1.

“200,000 Expected at Lotta’s Fountain,” San Francisco Examiner, December 23, 1910, pg. 3.

“Two Hundred and Fifty Thousand Hear Tetrazzini Sing in the Open Air Before the Chronicle Building,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 25, 1910, pg. 27.

Walter Anthony, “Diva Sings Gloriously to Stilled Throngs,” San Francisco Call, December 25, 1910, pg. 29.

Ralph E. Renaud, “Great Artist Reveals Her Very Soul to the People She Loves,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 25, 1910, pg. 27.

Frederick Wood, “Queen of Song Sings from her Heart to Worshipful Throng in San Francisco’s Streets,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 25, 1910, pg. 27.

“Tetrazzini Must Pay,” New York Tribune, July 27, 1911, pg. 7.