Woody Grab Bag #003

Long before Nazis there were swastikas—around the world and in San Francisco. Plus, what happened to Engine Company 12?

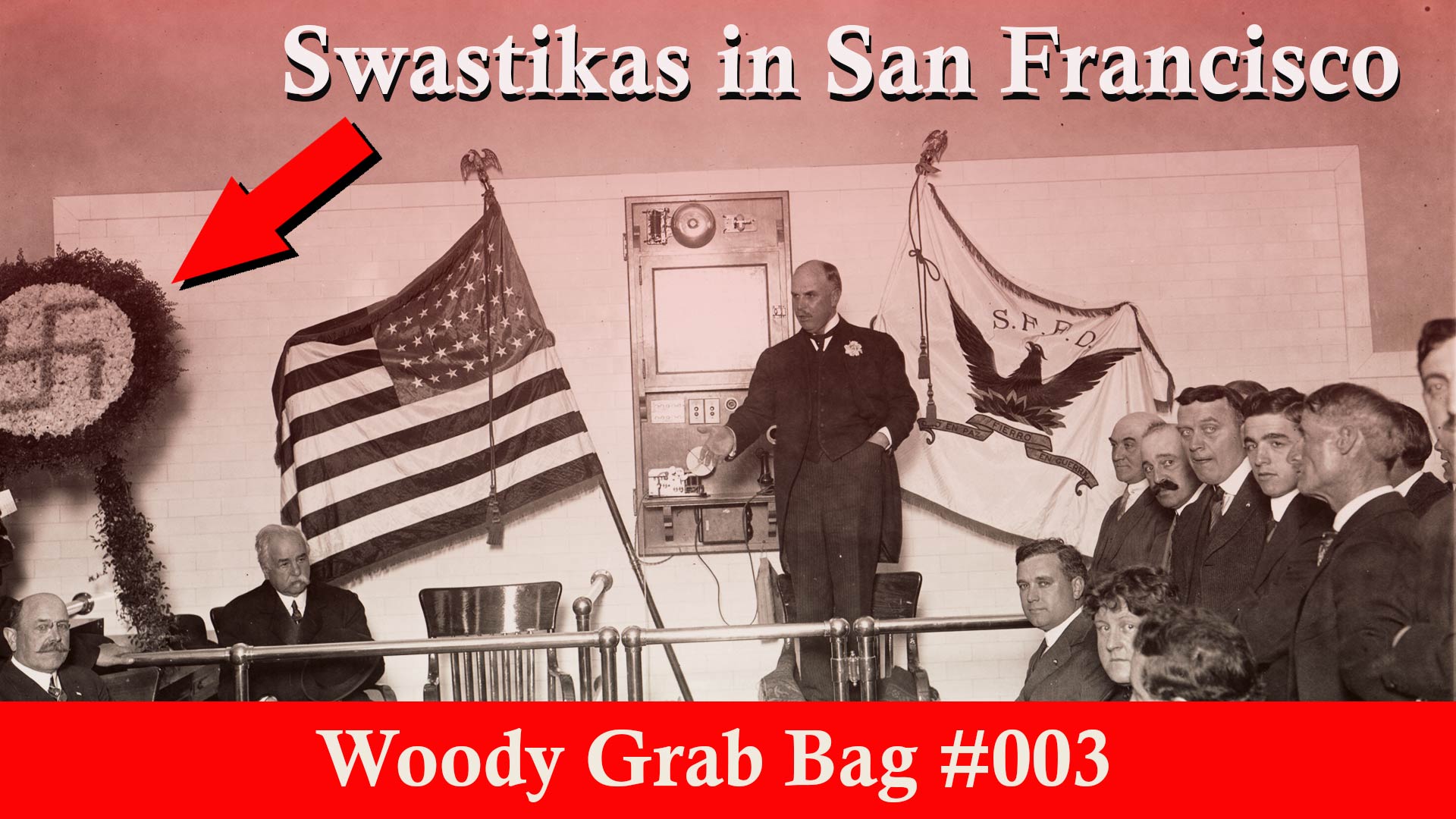

One hundred and seven years ago this month, San Francisco mayor James Rolph gave some remarks at the dedication of the city’s newest fire station at Commercial and Drumm Streets. The city photographer memorialized the fairly mundane event with a strange composition.

The mayor is standing on a chair, his feet inside a wadded-up rug to protect the seat or perhaps provide some traction for the mayor’s balance. The group of dignitaries close to the dais look uncomfortable, even a little fearful to me, as if they had all gathered as part of a plot from which they weren’t sure they’d escape with their necks. Perhaps I get that sense less from their expressions than from the swastika flower arrangement propped on top of the desk to the left.

In 2020, US Senator Dianne Feinstein almost had her name removed from a public school in San Francisco's Parkside District when a committee assigned by the school board dinged her for flying a Confederate flag in Civic Center while mayor in the 1980s. A swastika prominently displayed in a city building seems far worse.

But this fire station dedication was almost two decades before Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the Nazi appropriation of an ancient symbol. The “broken cross” swastika appeared in cultures from India to the Americas for thousands of years before the National Socialist German Workers' Party. Late 19th century archaeological digs helped make ancient symbology fashionable and by the early 1900s the swastika had become a design element widely interpreted as conveying good luck.

The San Francisco Chronicle noted its popularity in 1907: “The mystical ‘Swastika’ design of four points—about which every one is talking in the East—has now reached the craze point in this city. […T]his curious sign has been worked out in the form of brooches, watch fobs, match boxes, cuff buttons, pins, bracelets and belt buckles…”