Bicycle Bandits Hit Ocean Avenue

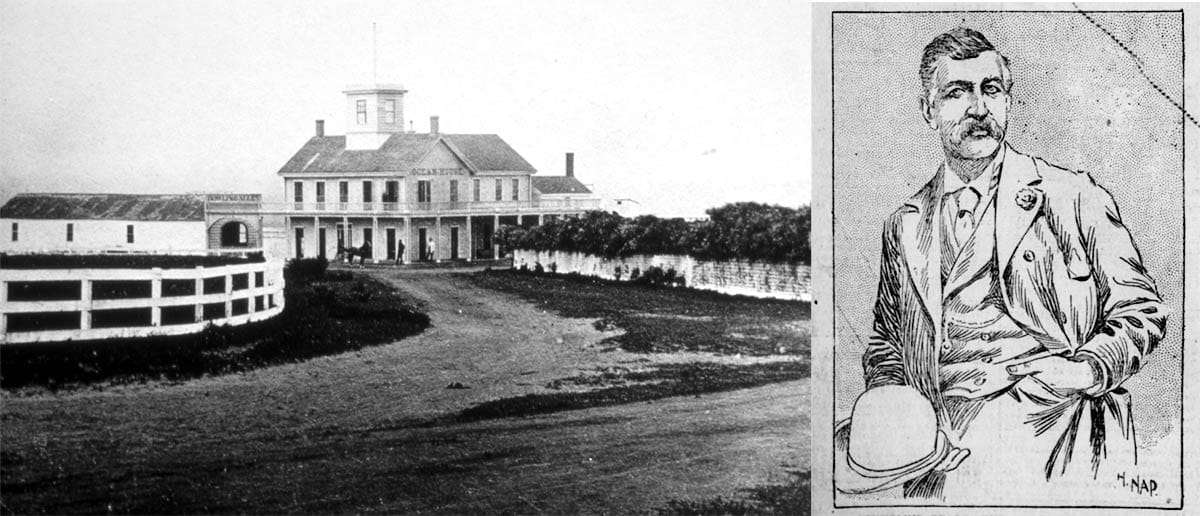

San Francisco's Ingleside Inn was the end of the line for famed host Cornelius Stagg.

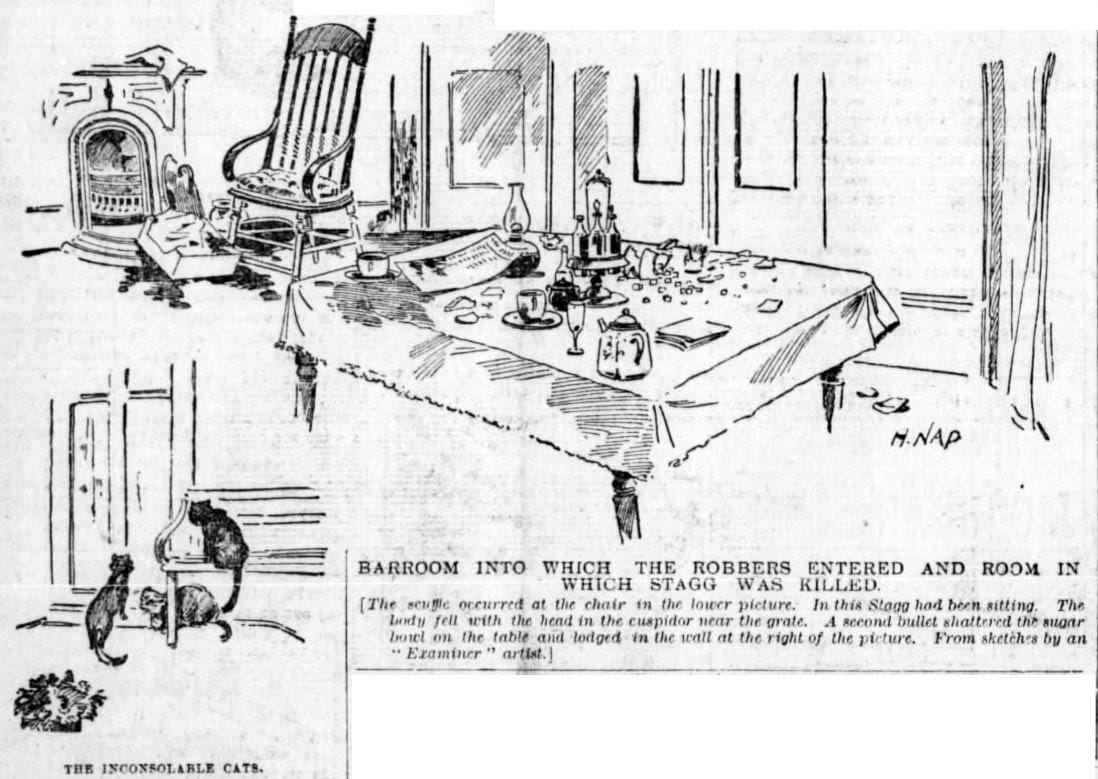

Sixty-eight-year-old Cornelius Stagg sat in front of a fire reading a newspaper in a parlor of his Ingleside Inn a little before 10 p.m. on March 16, 1895. His hired man, Robert Lee, sat in the opposite corner reading his own.

The career of the sporting man and roadhouse host had had its peaks and valleys, from entertaining people like Buffalo Bill, the king of Hawaii, and other heads of state, to being on the verge of financial ruin multiple times.

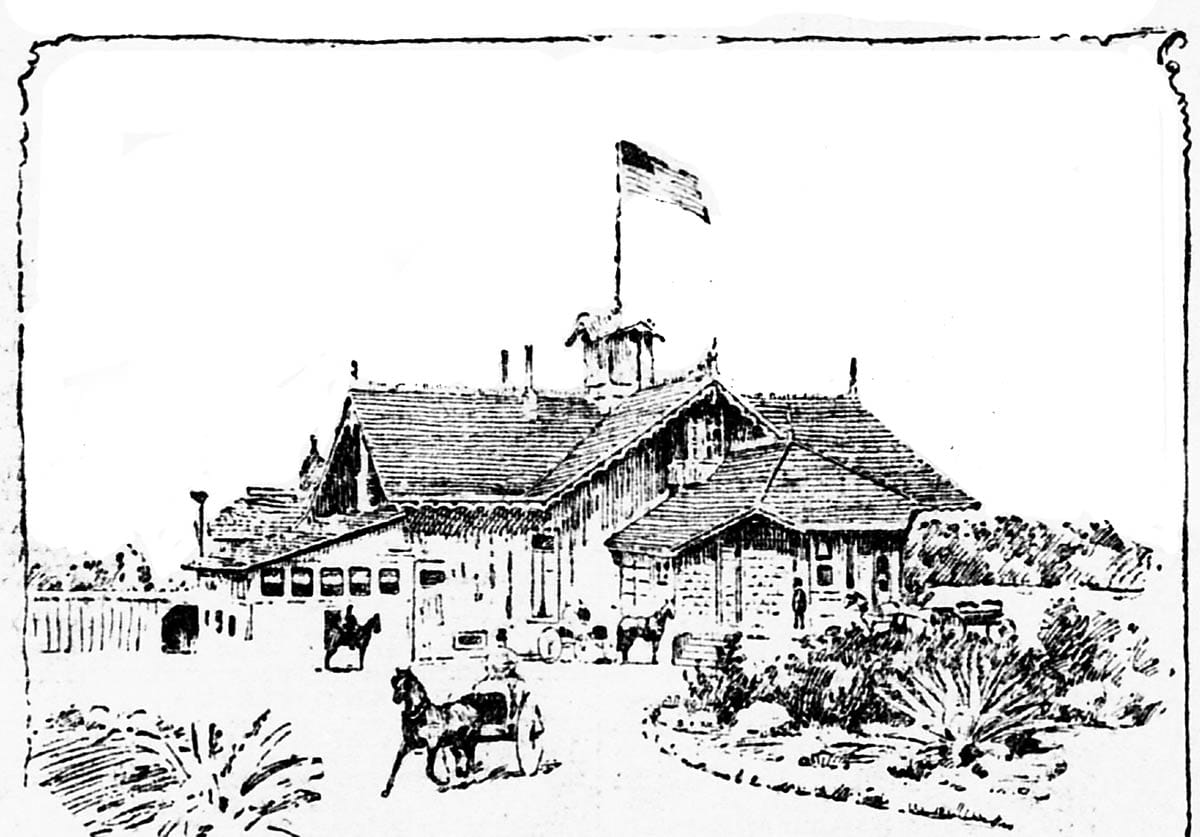

He was long separated from his beautiful but fractious wife, had no children, and the Ingleside—a small roadhouse surrounded by vegetable fields in a foggy corner of the city—was his last venture.

It could still pay off. There were plans in motion by rich men to build the west coast’s premier horse-racing track a couple of hundred yards from his establishment. The crowds on race days could be a gold mine for Stagg.

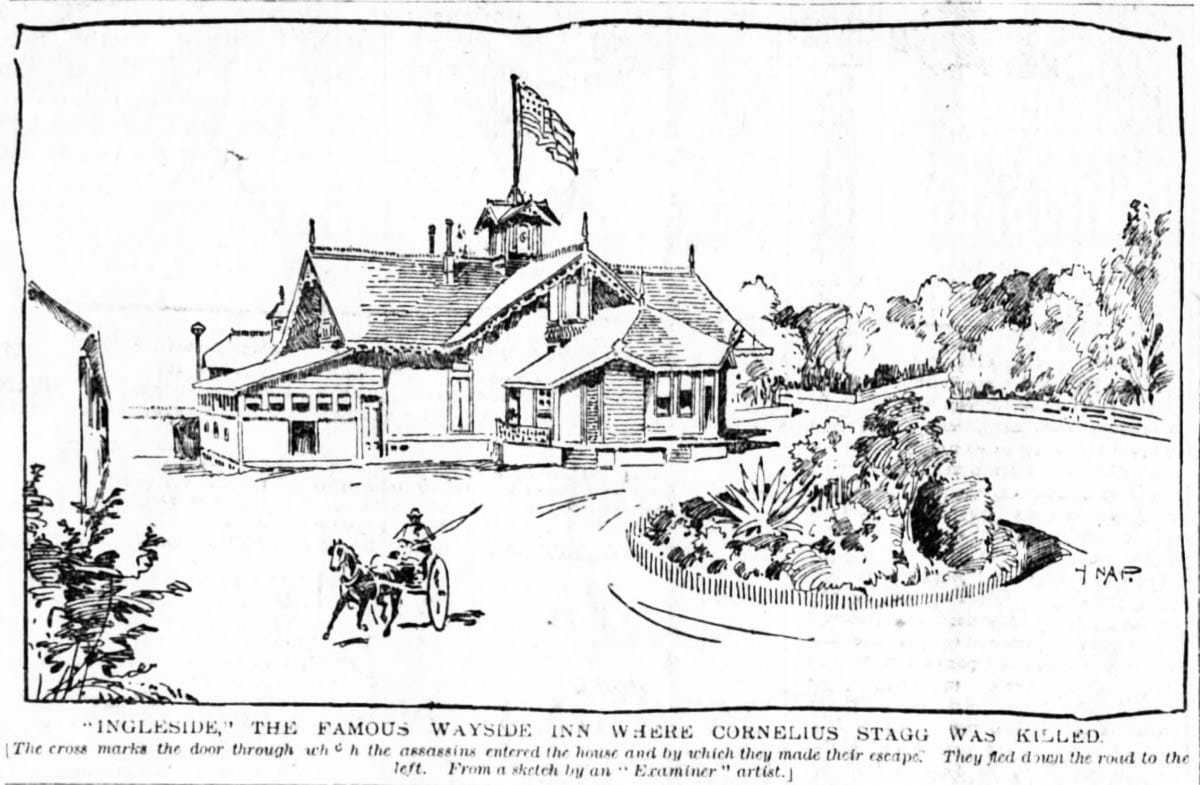

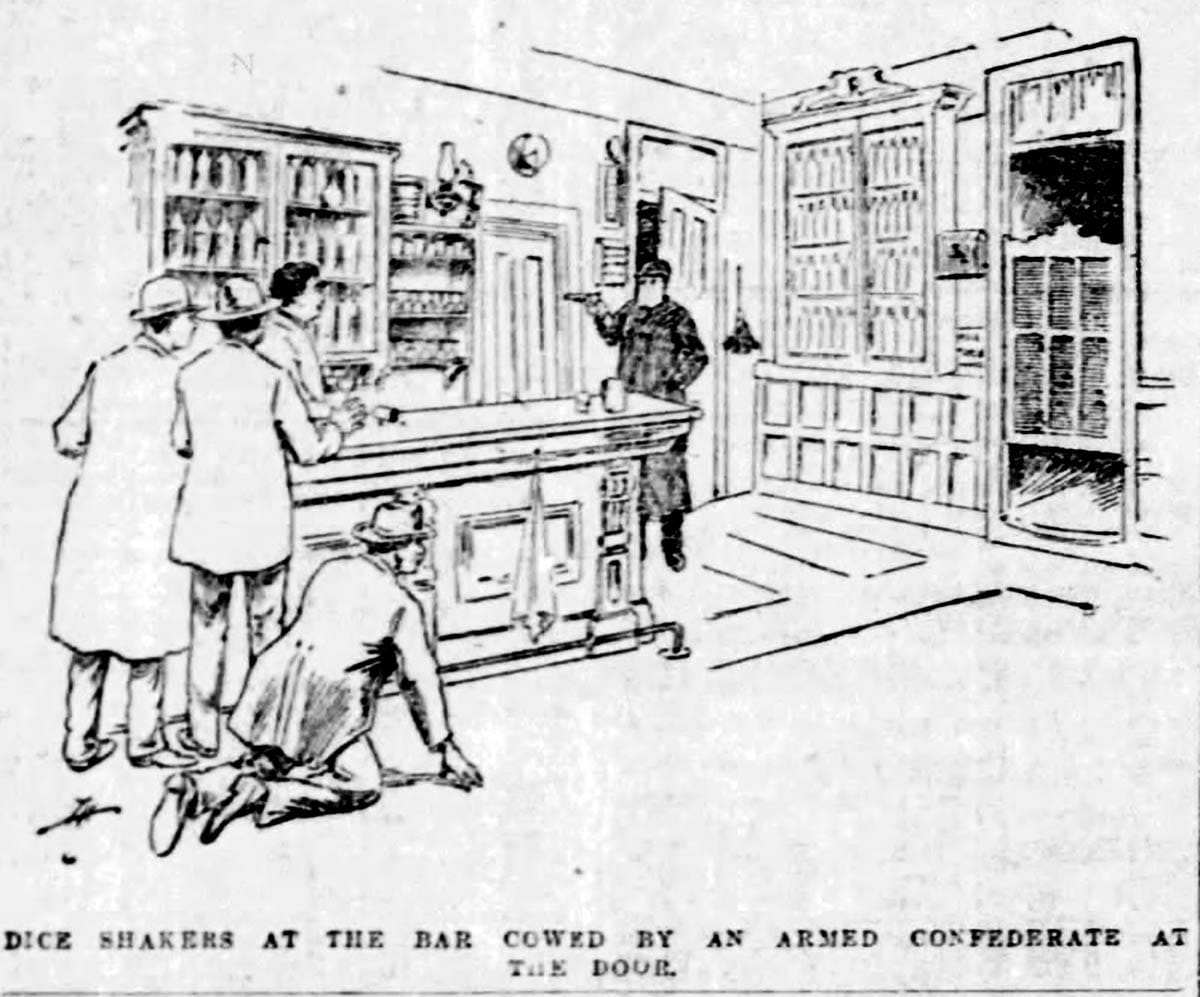

But that potential seemed a long way off on that Saturday night. There were only three customers in the bar playing dice with his assistant manager before two men quietly entered through a side door. Stagg might have heard them talking outside before one of the newcomers appeared in the doorway of the parlor.

He was tall, masked, wore a long linen duster, and held a gun. Stagg and Lee, newspapers in their hands, froze in surprise.

The man strode over to Stagg while keeping the hired hand in his sights.

“Get up and go to the bar.”

The old roadhouse host had dealt with a number of hold-ups over his long career. While short in stature, Stagg was always “game” and was used to brazening his way out of jams. “What will I do that for? I’ll do nothing of the kind.”

The masked man struck Stagg in the face with his revolver. As the arm went up for a second blow, Lee, the hired man, made a break for it out the back door. He heard two shots ring out behind him.

When the police arrived, they found Cornelius Stagg dead on the floor, shot through the head. The bandits had taken the contents of the till, all of $4, before disappearing into the dark night.

No one had heard horses. The police concluded their prey must be on foot and began a search of the countryside.

Despite false leads and reported sightings, the killers of Cornelius Stagg were still considered at large two days later. Nervous residents of the lightly populated southwestern quarter of the city took potshots at shadows in the night. Tall men with questionable pasts continued to be rustled up and interrogated by the police.

Then investigative detectives from San Joaquin County arrived in town with a theory and some news.

Stagg’s killers were the notorious bicycle bandits.

Rise of the Wheel

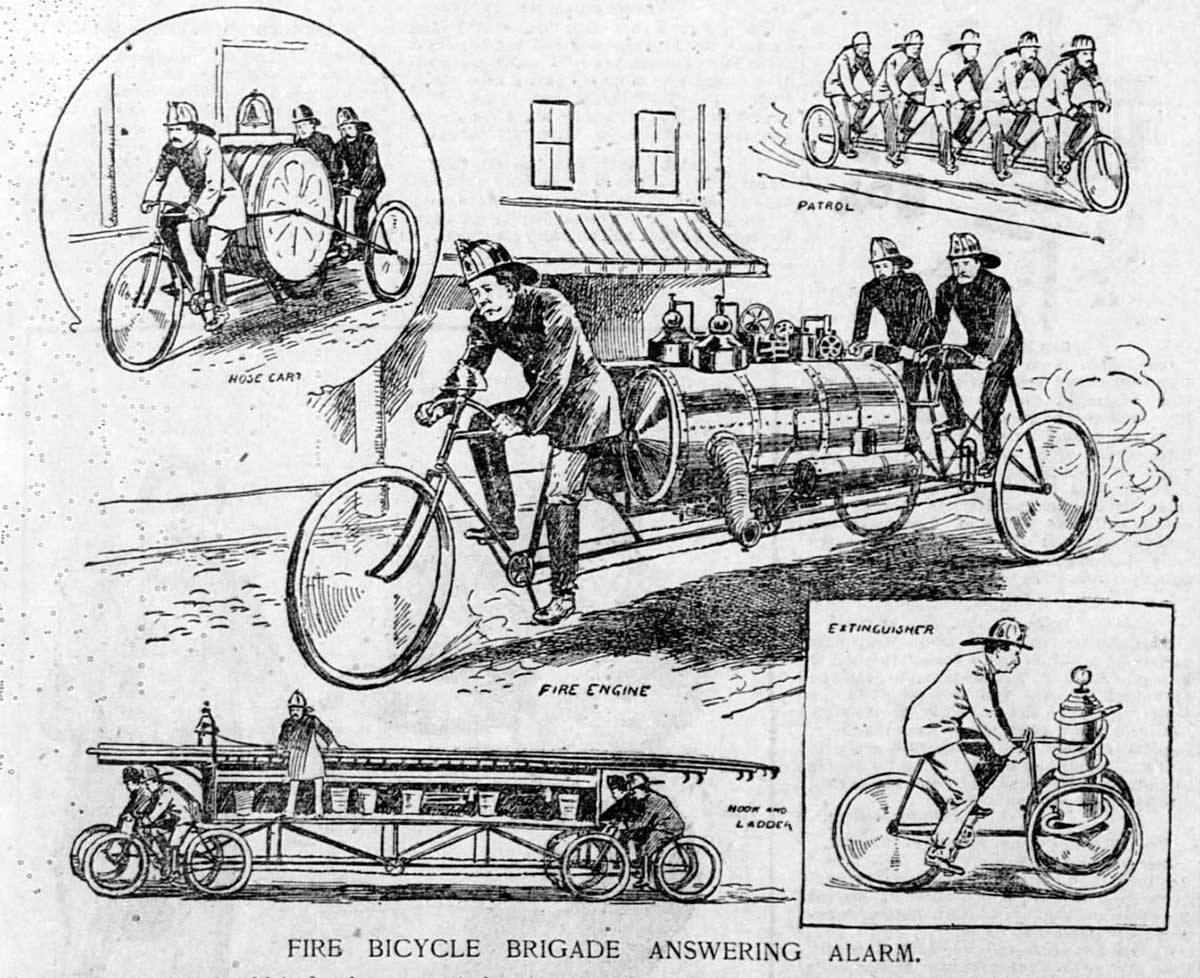

In the mid 1890s, bicycle mania had San Francisco in its grip. Everyone was bicycling, talking about bicycling, trying to make money off bicycling. Bicycles were going to replace the horse. Bicycling was the great liberator of women. There were bicycle poems, bicycle songs, articles on bicycle fashion, worries about “bicycle hump,” and advice to avoid “bicycle face” (looking too stern).

Bicycle tracks were constructed, bicycle guides printed, bicycle clubhouses made out of old transit vehicles at the beach.

Like AI in 2025, every one was trumpeting, appending, and plain smooshing bicycle technology into every field and occupation. There were real and proposed inventions for fire-fighting bicycles, war bicycles, submarine bicycles.

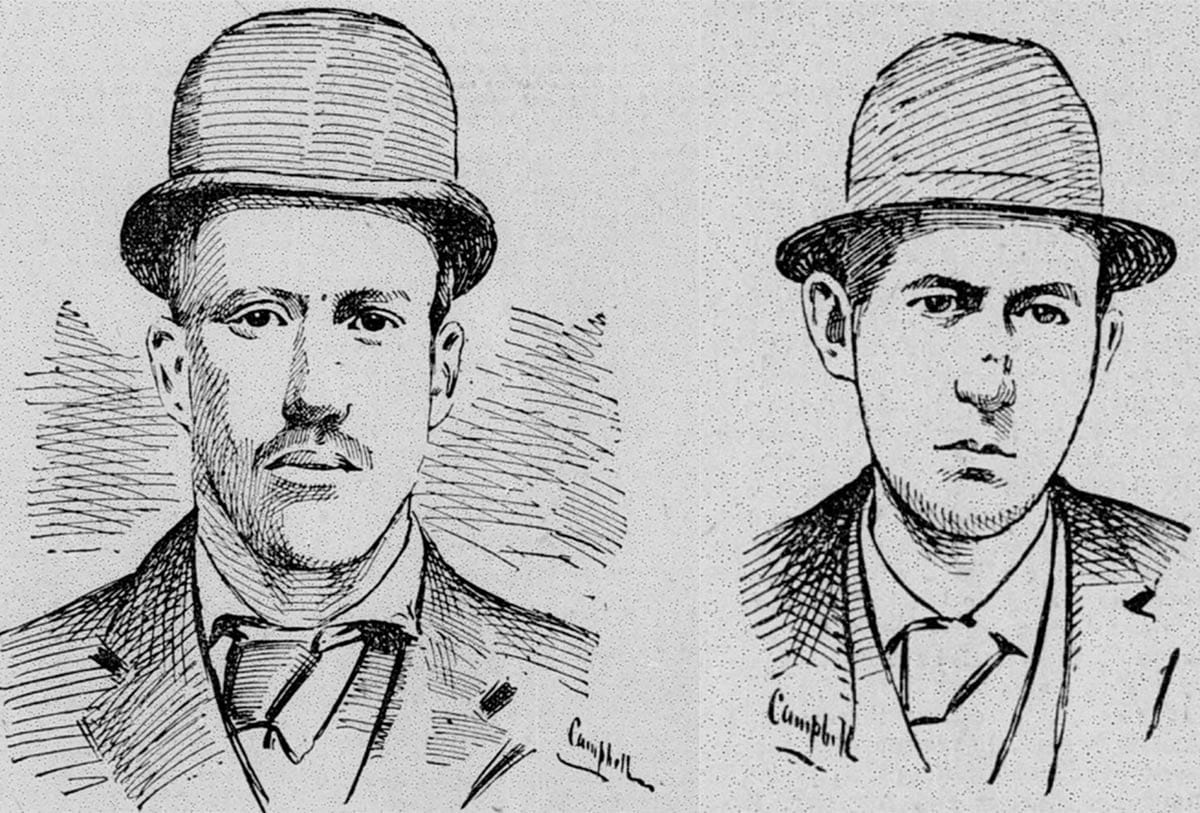

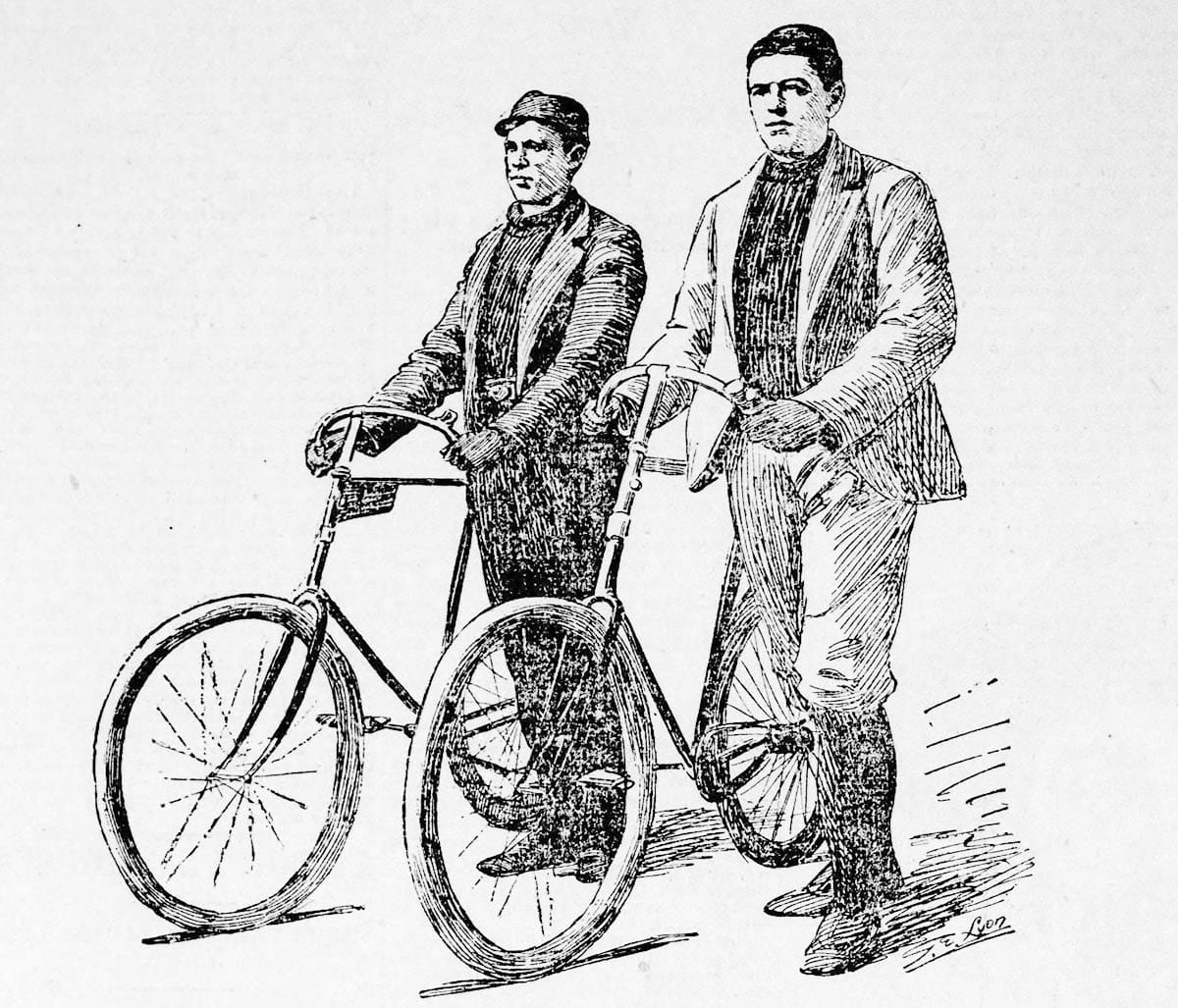

Two young ex-cons, Jack Brady and Sam Browning, caught the wheel craze themselves after their release from state prison. In the bicycle they saw felonious potential. Unlike a horse, a bike was relatively quiet and easy to hide. One could get across open and sometimes rough country faster than walking. Bicycles were harder to track or monitor than streetcar or train lines.

From the fall of 1894 to the spring of 1895, Brady and Browning allegedly robbed resorts, bars, and, most daringly, trains in San Francisco and inland counties.

Sheriffs from San Joaquin and Stockton counties, assisted by detectives from the Southern Pacific and Wells Fargo companies, delivered to San Francisco police an atlas of the wheeled duos’ criminal adventures. Bicycles were suspected as the mode of approach and escape in most:

After robbing a Sacramento saloon and then a brewery in August 1894, in San Francisco the pair held up and shot bartender Robert D. Haggerty at the Cliff House on September 25, 1894. They made a big score robbing more than $50,000 from an express train in Yolo County in October, and then were back in the city to hold up the Golden Gate Villa bar at Ocean Beach on February 21, 1895.

Various saloon robberies across the winter in the Mission and Western Addition were laid at their feet.

On March 3, 1895, in linen dusters and masks, Brady and Browning stopped and robbed an eastbound train just four miles outside of Sacramento. On March 8, 1895, they hit a northbound express eight miles from Stockton.

After killing Stagg and getting little from the Ingleside Inn on March 16, the bandits returned to the Central Valley to hold up the Oregon Express south of Marysville on March 30. The train fireman, with a gun stuck in his back, was forced through the cars with a sack to divest passengers of their cash and valuables.

But one of these passengers was Tehama County sheriff, John Bogard. As the engineer and Browning approached, the sheriff straightened and shot the tall desperado. The other bandit, Brady, shot the sheriff. The two exchanged gunfire around the engineer and cowering passengers. “Windows were shattered, woodwork splintered and great holes plowed in the wooden floor.”

As Browning lay dying beside the mortally wounded sheriff, his masked partner leapt from the train and disappeared in the night.

At the Marysville morgue the next day, a Chronicle reporter described the dead bandit: “His attire, which was that of a bicyclist—sweater, knee-breechers and dark stockings—tell the tale of the robbers’ ride to the scene.”

Indeed, that same day, a single bicycle was found under a bridge not far from the robbery site. The Westminster brand had a label identifying that it was hired out from Perkins & Walker on Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco.

Manhunt

The death of Browning opened everything up for the Stagg investigation. Detectives hit the lodgings of both the dead man at 626 Golden Gate Avenue and his close friend Jack Brady at 305 Grove Street. Tintypes and photos of the men on their bikes were found. Bicycle-rental employees, witnesses near the train hold-ups, and young ladies the men rode bicycles with in Golden Gate Park all identified them from photos.

Brady’s landlady at 305 Grove street said “he always acted like a perfect gentleman.”

Walter G. Haxe, “a young man of means,” who was a bicycle buddy of Browning reported the dead bandit as “mild-mannered, gentle and well-behaved a young man as he had ever met.” Over the past six months the two had rode nearly every day through Golden Gate Park and to the Cliff House, sometimes with Jack Brady. Haxe did note the pair disappeared from town at times coinciding with the train robberies.

Now the San Francisco police confirmed what they said they had kept secret about Stagg’s killing: traces of two bicycles were found near the Ingleside Inn the day after the robbery.

Brady was still at large. His description—five-foot-seven, two gold teeth—was shared widely. Solo bicyclists were closely scrutinized from Merced to Redding. A second bicycle with a San Francisco pedigree was found in Sacramento and some discarded bicycle pants in Chico.

It would take three months to catch Jack Brady. When found sleeping under a bridge in July outside Sacramento, he surrendered without a fuss and cheerfully confessed to much of the crime spree. He denied, however, being involved in the jobs in which Stagg and Bogard were killed.

While Brady awaited trial, detectives discovered that a good deal of the $50,000 in gold that Browning and Brady had stolen from the express train in Yolo County had been buried near the robbery site. A “German tramp” had discovered it and lived on the high hog for months.

On November 19, 1895, the jury gave Jack Brady a life sentence for his role in the killing of Sheriff Bogard. During his incarceration, most of which was spent at Folsom Prison, Brady tried to escape at least four times. The rumor was he had more ill-gotten treasure buried somewhere.

Jack Brady was paroled in 1913 over many people’s objections. A fellow prisoner called him “a broken-down man—an old man at 45,” and wrote that after his release the old bicycle bandit lived and worked with a friend in the Sierra foothills.

But he might have returned to the Ingleside Inn for a drink. While a shadow of its old glory days without its legendary host, the roadhouse ran under different operators as a bar and restaurant until the 1920s when it was demolished for a gas station.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thank you for all the good wishes on my 60th birthday. It was terrific to see so many of you and to spend some of the Woody beverage fund on behalf of good conversation. I also can not believe we ate so much See's candy...

I know I owe folks emails! Starting to attack the stack and schedule more drink meet-ups, especially as Mike P., Richard L., and Luba M. (all F.O.W.s) have generously added to the beer and coffee reserve!

Sources

“Shot Down by Masked Men,” San Francisco Call, March 17, 1895, pg. 14.

“Deadly Fight with Train Robbers,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 31, 1895, pg. 11.

“Reeds’ Train Robbers,” San Francisco Call, April 1, 1895, pg. 1.

“Murder their Pastime,” San Francisco Call, April 2, 1895, pg. 5.

“Three Murderers on Bicycles,” San Francisco Examiner, April 3, 1895, pg. 1.

“Bandit Brady Safe in Jail,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 27, 1895, pg. 1.

“Events of One Day on the Coast,” San Francisco Examiner, July 30, 1895, pg. 3.

“How I Cartooned My Way Out of the Penitentiary,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 31, 1914, pg. 3.