Electric Tower

Light shows in Golden Gate Park aren't a new thing.

You may have walked through the Lightscape show in Golden Gate Park over the holidays. San Francisco’s Rec and Park department and its associated nonprofits have leaned into electric light and projection shows as Instagram-worthy methods of “activating” the park at night and making a few bucks.

Light shows can be promoted as public art (and maybe they are). They are apparently endlessly fund-able. They can easily be incorporated into events where drinking and merry-making are the meat and potatoes. (Lightscape was very family-friendly.)

While light shows may feel trendy (or at least did 10 years ago), the idea of drawing crowds to Golden Gate Park with electric spectacle dates back 130 years.

Lighting up the Winter

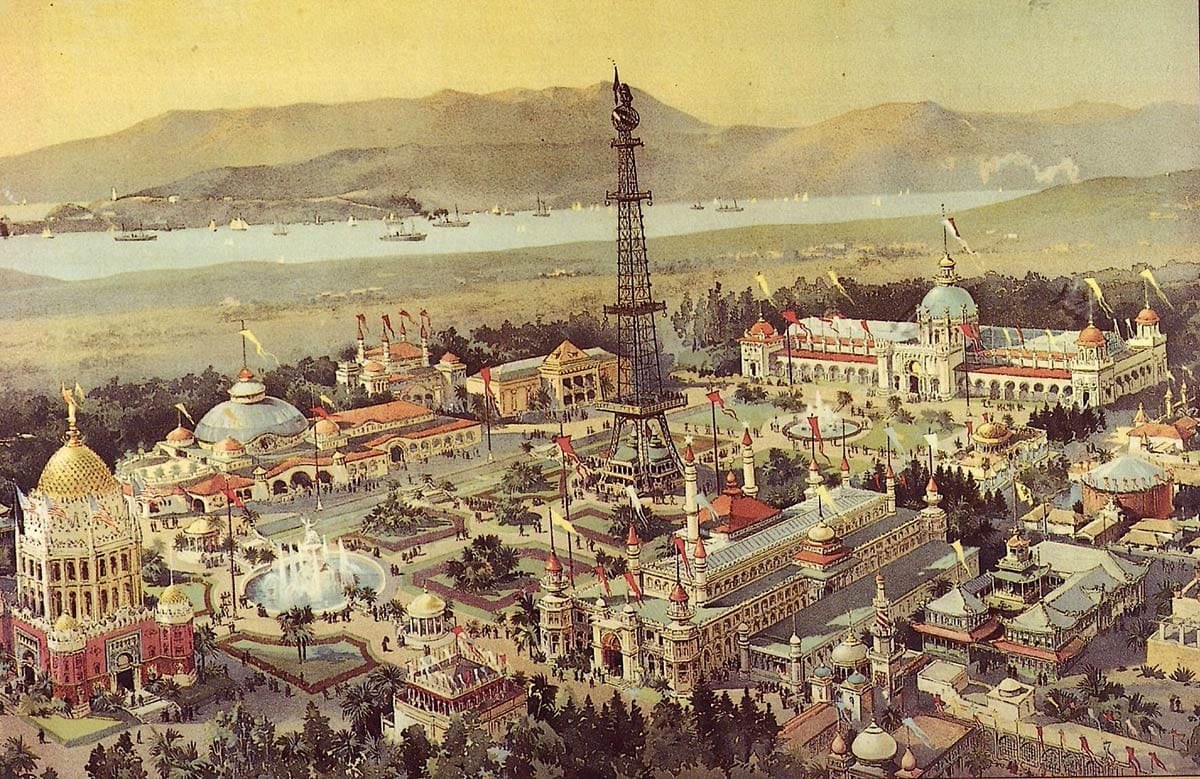

While attending Chicago’s huge 1893 Columbian Exposition, a true world’s fair, San Francisco leaders had the idea of recycling its attractions and acts in Golden Gate Park the following year for a “California Midwinter International Exposition.”

What better way to advertise to the nation—nay, to the world—the salubrious, business-friendly climate of the Golden State than to host a mostly open-air exposition in Golden Gate Park in January when it was freezing in Midwest and Eastern cities?

That question was rhetorical. A midwinter fair was the answer. Here are ten highlights.

Today’s Music Concourse was created as the “Grand Court” of the Midwinter Fair. In contrast to the all-white motif of the Columbian Exposition, San Francisco went for a colorful Moorish-influenced design for the main fair buildings.

Leopold Bonet, an architect and designer at the Chicago expo, had unsuccessfully pitched a knock-off Eiffel Tower attraction there. Now, California gave him a second chance. Since the San Francisco fair directors were keen on lighting up the grounds in the evenings, Bonet tossed in a bulbs-everywhere-scheme and branded his proposal as the “Electric Tower.”

San Francisco bit. In September 1893, a preview of the tower plan was released to the press.

Five thousand incandescent lights of different colors would be draped over the tower and “turn night into day.” There would be four separate viewing galleries able to hold “8,000 people...at one time.” A mighty searchlight used at the Chicago expo would pan the city from the top of the tower. The pinnacle would be topped by a California bear atop a large gold ball.

Restaurants at the tower’s base were to be “designed after Moorish ideas of architecture with quaint minarets and lattices wrought in arabesques,” but, to assuage local tastes and perhaps patriotism, “within there will be served good, palatable American Viands.”

The Midwinter Fair opening was planned for January 1, 1894. With weather holding up exhibits traveling from Chicago and indecision by participants on the west coast—Santa Barbara County didn’t agree to have a building at the fair until January—the official opening of the fair was delayed until January 27, 1894.

Even with the delay, much of the fair was still under construction opening day, including the Electric Tower:

Most of the tower’s predicted glories did come to fruition, albeit in smaller degrees than promised. The tower rose 272 feet—2/3 the Eiffel Tower’s height—and its café on the ground floor did sport some Moorish window treatments. An elevator took people up to a viewing platform 210 feet high, where about a hundred people—not 8,000—could congregate to ooo and aah.

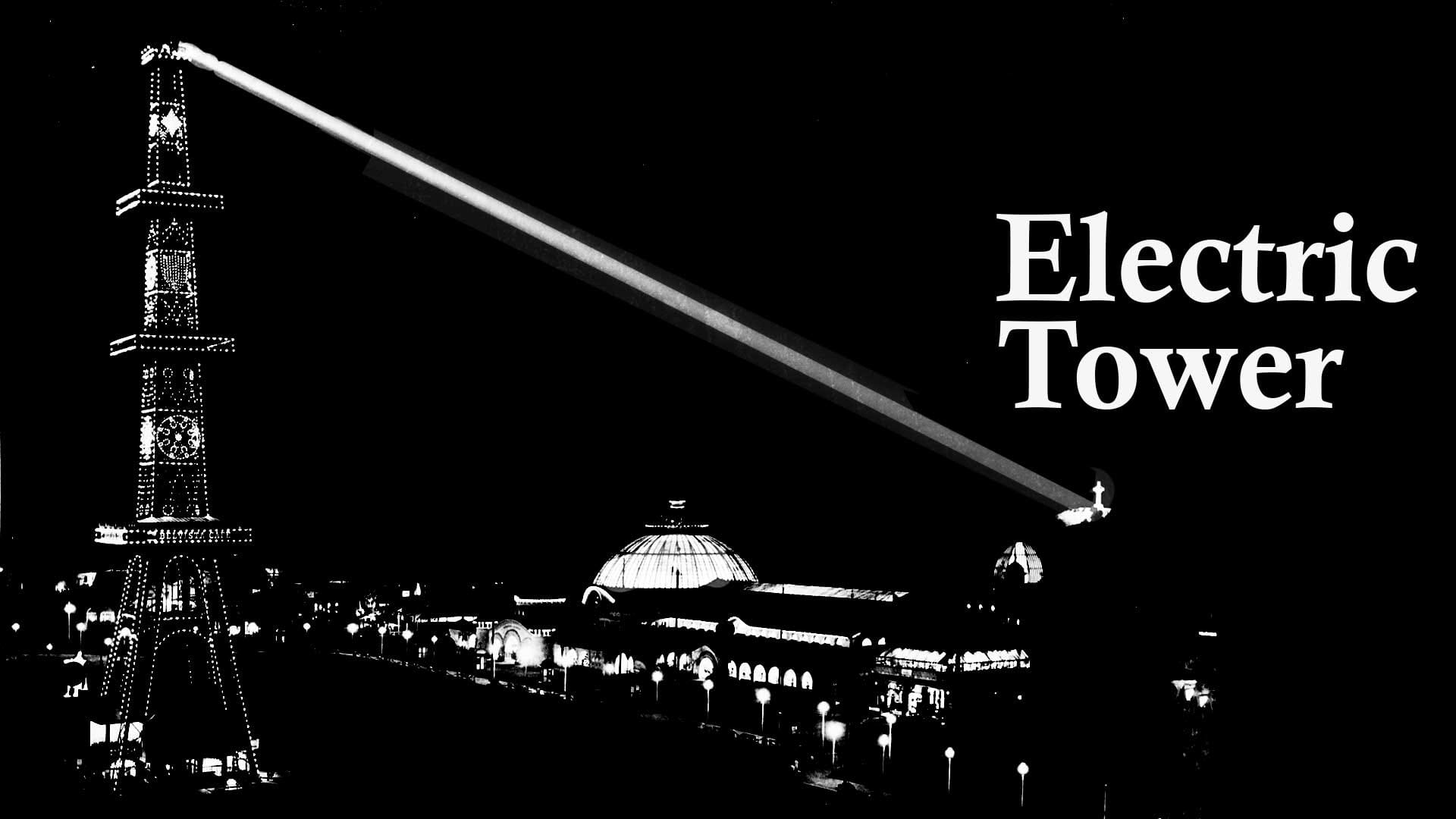

The searchlight arrived from Chicago, billed as the largest in the world at the time with a reported light-power equal to 350 million candles.

“[It] threw its strong arm of radiance out over all the surrounding country, illuminated the further shores of San Francisco Bay, and shone full in the faces of mariners coming in from the sea and steering for the Golden Gate.”

(Sounds a little dangerous.)

There were more than 3,000 lights on the tower: 1,000 outlined the iron form, 1,000 more created decorative shapes, and 1,200 were “programmable.” A music-box-like cylindrical mechanism could animate spheres, crosses, diamonds, and irregular rosettes.

The other fair buildings were well illuminated and outlined, but the Electric Tower was the show each night. Few attended without riding its elevator or having good, palatable American Viands at its café.

The total cost of the Electric Tower was reportedly $80,000, which would amount to more than $3 million in 2026. Did the concession pay?

“It did not pay,” reported the San Francisco Call, after the fair ended “and nearly every part of it, even to the concrete foundations, it is said, is the subject of some legal claim.”

Toppling the Tower

The Midwinter Fair officially closed in late summer 1894. The buildings and structures were all intended to be temporary, except for the one dedicated to Fine Arts, and had to be cleared out.

(The quasi-Egyptian Fine Arts building was later dedicated as a museum and named after main fair-booster and Chronicle publisher, Michael de Young. Today’s de Young Museum is its institutional descendant.)

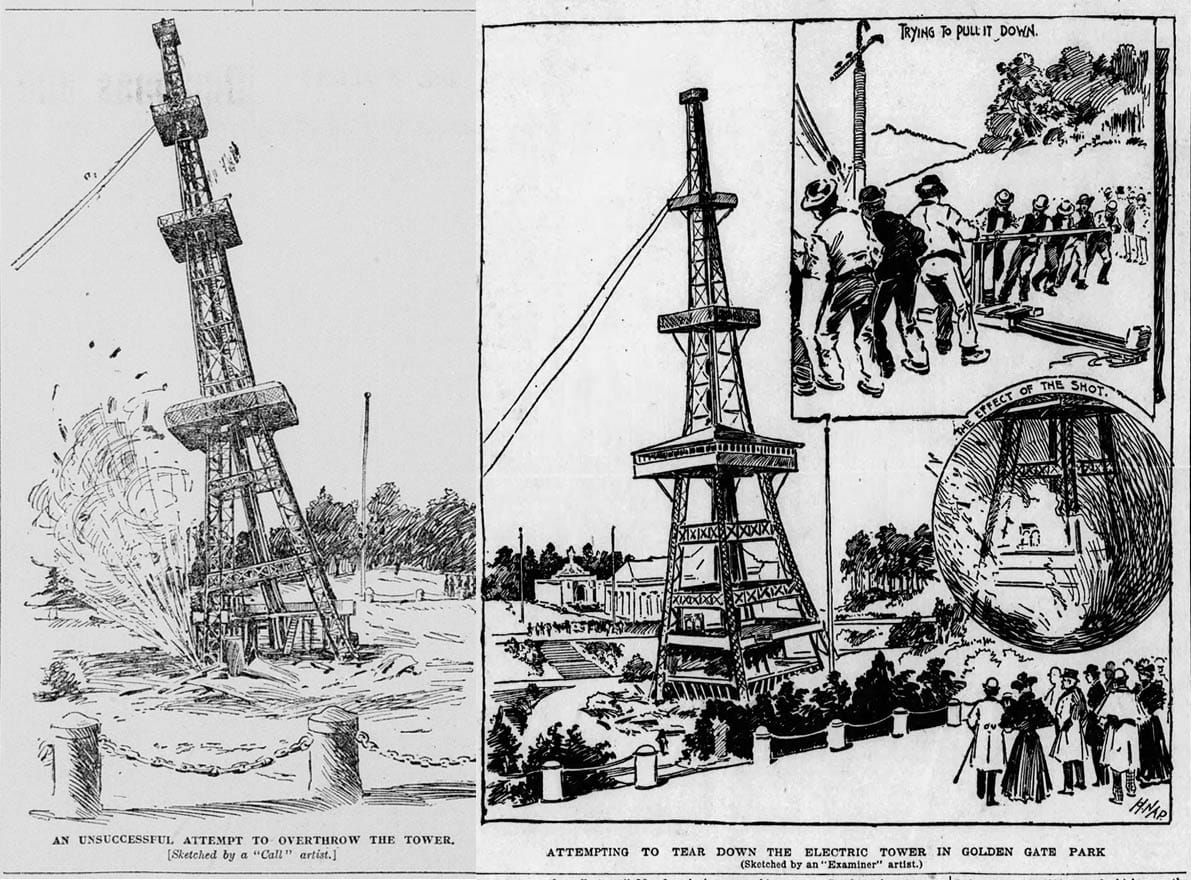

Crying poor and suing each other, the Bonet group left the city to deal with the 260-ton Electric Tower. Stripped and decaying, it was still standing a year after the fair’s closing.

“The youthful visitor to the park, who is not under any paternal or maternal restraint, has found a new source of amusement,” observed one reporter in October 1895: “climbing up to the first landing of the deserted electric tower and then ascending to the searchlight platform by means of the iron ladder.”

(Sounds a little dangerous.)

The Park Commissioners told park superintendent John McLaren to deal with the hazard. On January 11, 1896, he sent 20 workmen with a windlass, block and tackle, and a steel cable to pull the tower down.

It didn’t budge.

The men drilled holes in the concrete footers, stuffed in explosives, and set off a good dozen blasts. Flying debris crashed through the skylight of the new park museum.

(Sounds a little dangerous.)

Still didn’t move.

They yanked some more and set off more explosions.

The tower leaned slightly.

Exhausted and mocked by the crowd which had formed, the party decided to return on Monday after a good breakfast.

A park commissioner thought waiting 48 hours to deal with a giant leaning iron tower was a bad idea. He encouraged McLaren to bring a lot of dynamite on Sunday morning.

A big blast at the base of one leg finally did the job.

“During the afternoon the fallen monster was visited by a large number of people,” wrote the Call, “each carrying away a bit of iron or a splinter as a memento.”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to Karen P. (F.O.W.), Craig L., Paul T., and Leslie L. (F.O.W.) for saying “Gee heck, Woody, you need to make sure to have a sociable beverage with a nice person now and then. Here is a donation to pay for the drinks and subtly pressure you to do it!”

It works! Anyone reading this: let me know when we can get together and chat over a cappuccino or chin-wag over a cider.

Sources

Taliesin Evans, All About the Midwinter Fair (San Francisco: W. B. Bancroft & Co, 1894)

“A Unique Feature Secured,” San Francisco Examiner, September 13, 1893, pg. 4.

“A Horticultural Exhibit,” San Francisco Examiner, September 14, 1893, pg. 4.

“Sutro’s Midway,” San Francisco Call, September 3, 1894, pg. 3

“At the Park and Beach,” San Francisco Call, October 7, 1895, pg. 4.

“With Powder and Rope,” San Francisco Examiner, January 12, 1896, pg. 16

“That Tottering Tower,” San Francisco Call, January 12, 1896, pg. 7.

“The Park and Vicinity,” San Francisco Call, January 13, 1896, pg. 8.