Fighting Flu in Civic Center

The Red Cross planned one thing and got another in 1918 San Francisco.

Nancy needed a new phone. Off to the Apple store we went last week.

The older woman helping us wore a mask but her nose was not properly covered up; it was as clearly visible as… well, the nose on her face. Probably she had the eyeglasses-fogging-up issue.

While some have never let down their guard, most of us walk around mask-free now, shaking hands and remembering to forget all that pandemic stuff.

Seeing masks doesn’t usually put me back in 2020. They are relatively common in San Francisco, especially on the buses. But loosely worn they sometimes make me blink. My dormant pandemic brain is sparked, like when the detail of a dream pokes you in an afternoon moment.

Change of Plans

With donated land from the city and donated labor from local trade unions, the Red Cross opened a new building in the Civic Center in October 1918.

World War I had spurred expanded Red Cross operations in San Francisco. The organization was a primary way for people to contribute time and money to the war effort. Red Cross nurses and volunteers tended both to the needs of soldiers fighting in Europe and their families at home.

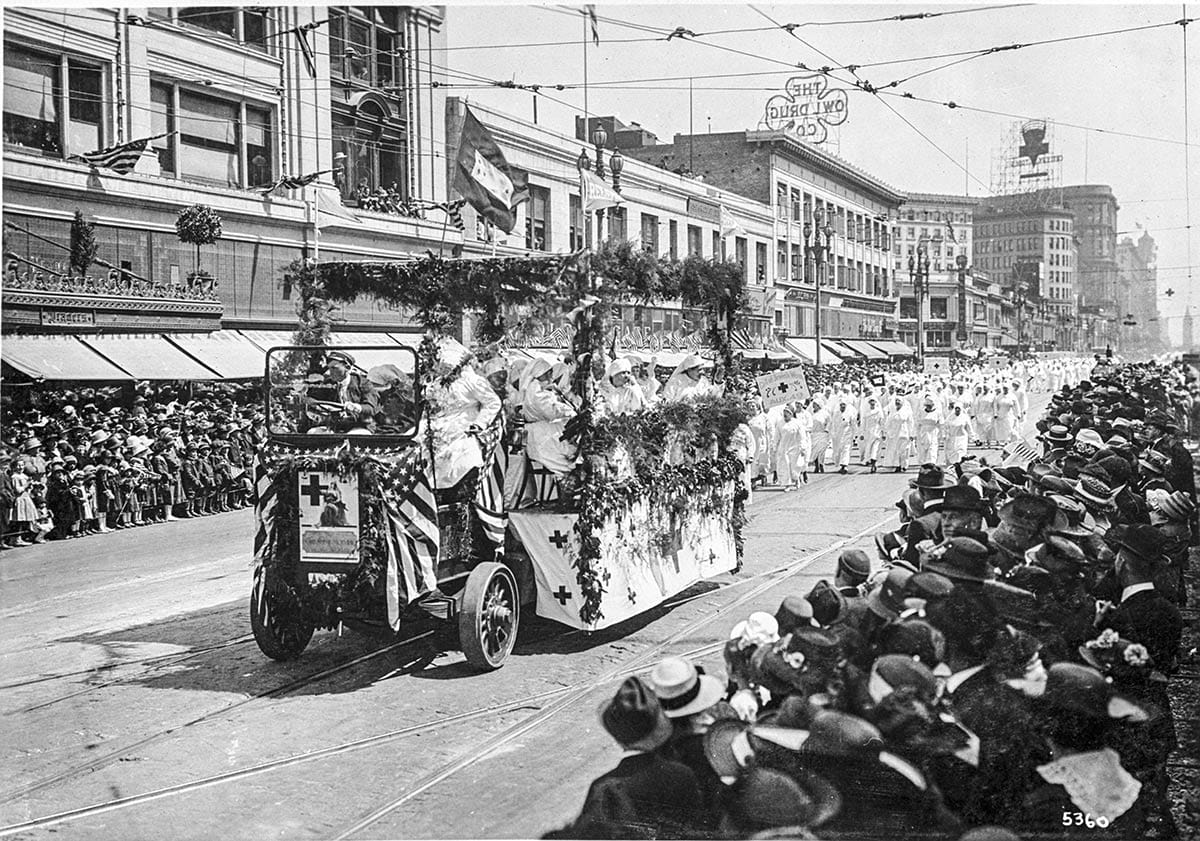

A giant citywide fund-raising drive had dominated newspaper headlines in the spring of 1918 and there was even a Red Cross parade.

The new Red Cross building was set on a small rise just off Hyde Street near McAllister. It was intended primarily for administrative and office work.

But before the doors opened, paperwork and even the war in Europe became secondary concerns. The influenza pandemic which would eventually claim 50 million people worldwide had reached San Francisco.

The media tried to be optimistic in late October 1918. Newspapers published hopeful reports of rapid abatement, possible cures, and a decline in cases—only 103 deaths on October 30 whereas there had been 124 the day before.

Adjacent columns told grimmer stories.

A popular newsboy succumbed and his colleagues raised money for funeral flowers. The police sick list ran to 140 names. Hospitals filled to overflowing, with 1,100 pneumonia cases at San Francisco General. The city Health Department commandeered other locations. Feverish people lay in long lines of cots in schools, churches, and even streetcar storage barns.

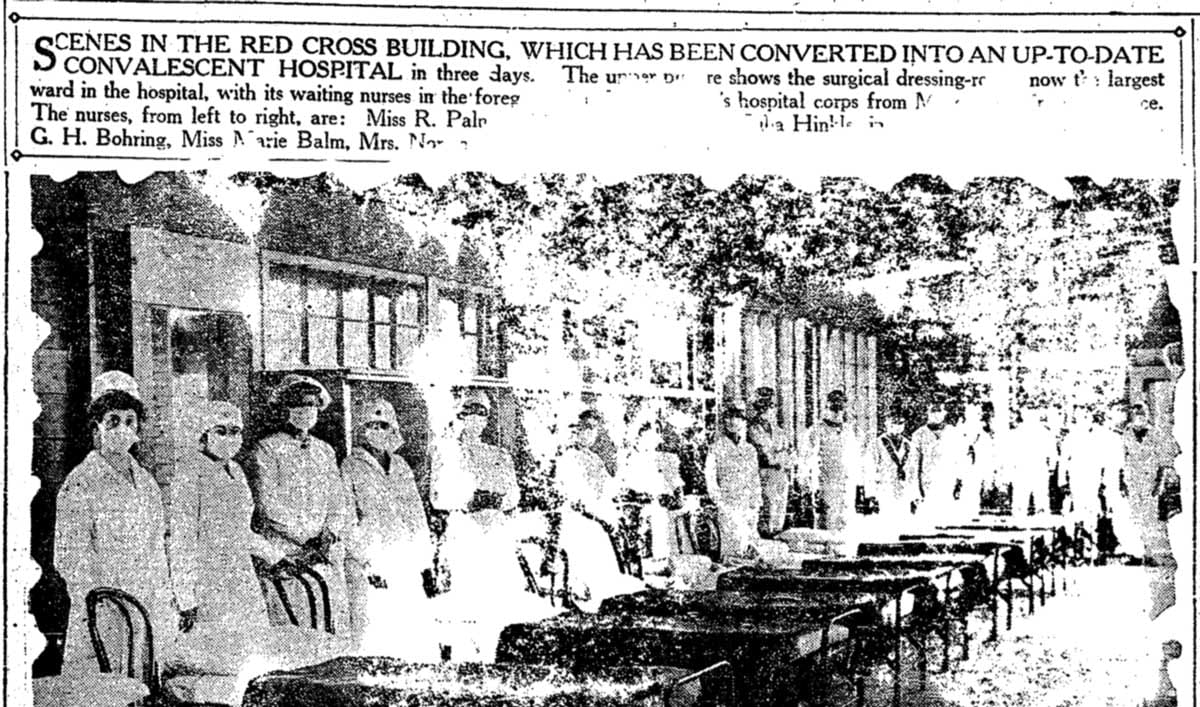

The Red Cross administration building, nearing completion, was quickly transformed into a 300-bed ward primarily for children. Many of the young patients came from North Beach, the so-called “Latin Quarter,” which was then a less prosperous neighborhood packed with large families.

“Over in the Latin quarter the struggle against the epidemic continues to be acute, and the mortality percentage alarming […] the trouble is the children. There are so many of them over that way, and ever so many of these are, by reason of their multitude, neglected. One family boasts a progeny of eleven. The mother is sick, the father is sick and some of the little folks are sick, too.”

Red Cross nurses, along with 40 sailors assigned from Mare Island, ran the temporary hospital through the height of contagion. Despite their efforts, in a city of 500,000, more than 45,000 San Franciscans would get sick and 3,000 would die from the flu over the next five months.

The Worst Year

We did better in our pandemic. We have about 840,000 people and the cumulative death toll from Covid-19 in San Francisco is currently at 1,410. We wore our masks better. We washed our hands for 20 seconds as instructed. We socially distanced.

But it was hard. George Floyd and unbreathable wildfire smoke and that bleak, bleak day when the sun didn’t come up but the sky turned orange weren’t World War I, but they pressed hard upon me.

My father died without us in a care facility in April 2020. No big church funeral as he would have wanted. In the graveyard my brothers and I had to stand masked, yards apart from each other, from our stepmother, from the priest, all together and alone.

I walked and walked the city when I could and turned my eye from the occasional newspaper box so I wouldn’t see the latest headline of doom and death and despair, the predictions of months, possibly years more of isolation, and life never returning to what it was.

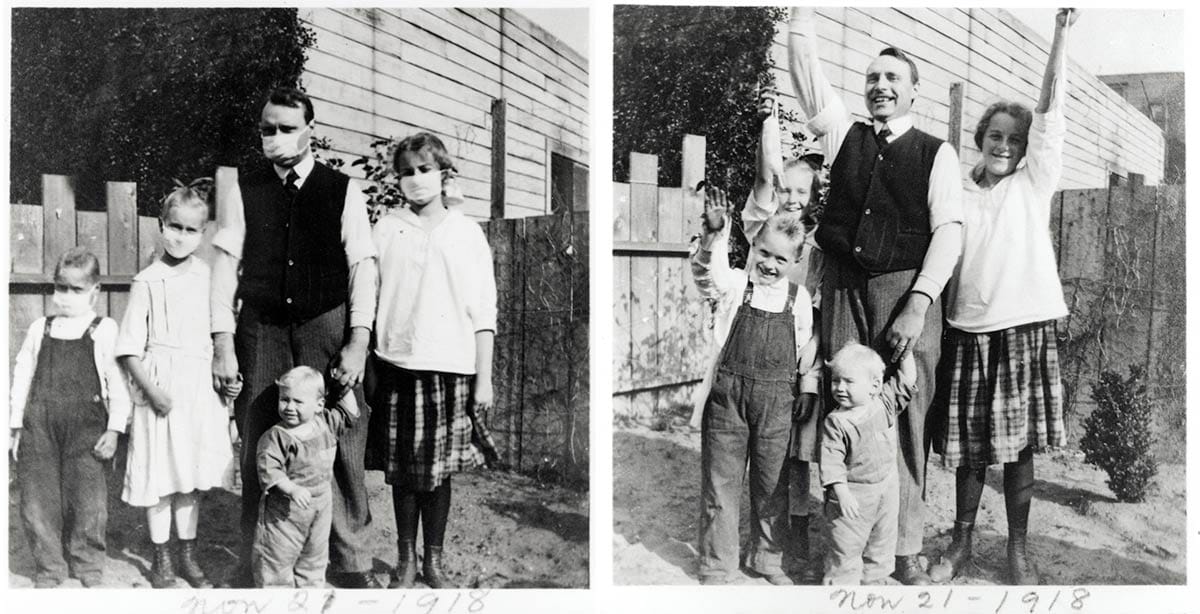

Weeks into our sheltering in place, Paul Judge sent an old photo in an email.

Taken in May 1919, it showed a reunion of his Uncle Mike’s forensic club in San Francisco. Less than a year after the flu had killed so many in town, here were young people crowded close together smiling and unmasked.

It was a strange beacon that lived in my head throughout the year, a little promise that something similar to before would be possible again.

The Other Side

By the spring of 1919, influenza disappeared from the newspapers and the war was over. The Red Cross administered to the needs of returning soldiers and their families and used the Civic Center building for its intended administrative purposes.

Veterans could apply for disability pensions and compensation at the office. A tearoom was available for servicemen in transit. An Army surplus store opened. The auditorium hosted university extension lectures on eugenics, Russian politics, and the psychology of advertising. Volunteers dropped in to sew and knit donations to be sent around the war-scarred world.

Eventually the Red Cross moved out. The building was used for Boy Scout meetings and high school classes while Galileo High was under construction.

In 1930, the city donated the land for a new federal office building. The Beaux Arts structure constructed between 1934 and 1936 completed the original Civic Center plan and still stands facing United Nations Plaza.

From what you can read, from what you can see in photos like Paul’s, the world got over the 1918 pandemic quickly. Right now, with some exceptions, it seems we have gotten there.

The end of the 1918 pandemic and the end of World War I were not the end of trouble. The Roaring 20s were not all jazz and flappers.

We think of Prohibition being about progressive tee-teetotalers, but it was also, if not primarily, a tool of enforcing cultural supremacy.

The country was growing more diverse with southern Europeans and Catholics. A white protestant anti-immigrant movement pushed for and used the 18th amendment to repress that trend.

The criminal justice system greatly expanded and—this won’t be a surprise—disproportionately arrested immigrants, black, poor and working-class. Where the police held back, extra-judicial racists rushed in. Between 1920 and 1925, some two to five million people in our country were members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Maybe all of that had nothing to do with the 1918 pandemic. Maybe it is now irresponsible to imply historical corollaries or compare their pandemic and our pandemic, their moment and our moment.

But fear, anxiety, and trauma are powerful elements which some people will always take advantage of to do terrible things.

Sometimes still, when I am washing my hands, I think, “Has it been 20 seconds?”

But mostly I don’t think to count.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

We can meet. We can have a drink, be it coffee, tea, or a Guinness. Your call, me pay. Folks like Jay R. (thanks, Jay!) contribute to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund just so there aren’t any awkward issues about who is buying for who. Let me know when you are free!

Sources

“New Red Cross Hospital Will Open Friday,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 1918, pg. 9.

“Red Cross Mercy Workers Aiding Stricken Children,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 2, 1918, pg. 9

Thomas R. Pegram, One Hundred Percent American: The Rebirth and Decline of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2011)

Lisa McGirr, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (New York, W. W. Norton & Co., 2015)