Grab Bag #61

A gaseous San Francisco history grab bag of hats, instant photos, and one famous recipe.

This is a giant Grab Bag, so in the spirit of the new year, I am making it open to one and all. Non-Friends of Woody, note what glories upon which you are missing out and consider becoming a member of this select (but accessible) coterie. We are generally good company.

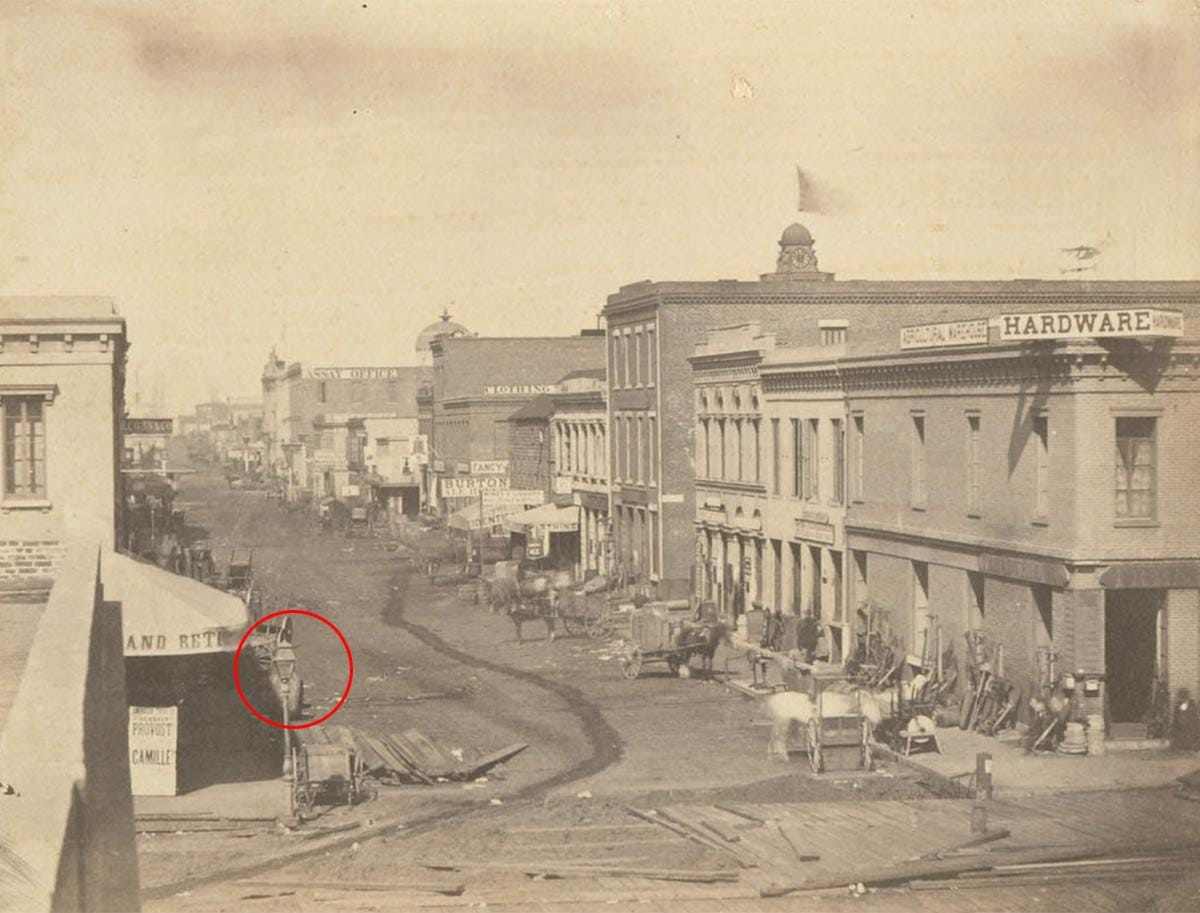

Guess Where

A new year, a new Grab Bag, a new Guess Where. The answer to this one will come a little earlier in this week’s narrative because I want to talk about that awesome lamp post below.

Where is this still-standing building in beautiful San Francisco?

Scroll on for the answer and more than you want to know about gas lamps.

Tetrazzini Leftovers

Thank you for all the kind words on my story about Luisa Tetrazzini’s Christmas Eve concert in 1910. To answer your question (if ChatGPT hasn’t), yes, the casserole dish “Chicken Tetrazzini” owes its name to the great soprano.

The origin story is a chef in New York or San Francisco so frequently made the dish for the famous opera star that it became named for her. The first references to it I can find are in 1909. Here is the recipe from Woman’s Home Companion, widely thereafter syndicated in newspapers around the country:

Chicken Tetrazzini

Melt two tablespoonfuls of butter, add three tablespoonfuls of flour, and stir until well blended; then pour on gradually while stirring constantly, one cupful of thin cream. Bring to the boiling-point, and season with one teaspoonful of salt, one fourth of a teaspoonful of celery salt and one eighth of a teaspoonful of pepper. Add one cupful of cold chicken or fowl cut in small thin slices, one half cupful of fresh mushroom caps cut in slices, one half cupful of cooked spaghetti and one third of a cupful of grated Parmesan cheese. Put into buttered ramekin dishes, cover with buttered cracker-crumbs, and bake until the crumbs are brown.

Send me photos of your success and let this vegetarian know how it tastes.

Tetrazzini did come off as a foodie. She often discussed her favorite meals with reporters. At the height of her popularity in 1909-1910 she even “wrote” a syndicated weekly column sharing recipes from her “private cookbook.” Each Sunday feature carried a staged photograph of the be-aproned diva working in the kitchen of her leased apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side.

Some part of Luisa may have been represented in the more than 20 columns, but a ghost writer definitely was at work with idioms, popular health advice, ethnic-food angles for each column, and American references.

For example: one week’s column was dedicated to recipes inspired by famous people and it seems unlikely that the Italian singer’s private cookbook contained “Grover Cleveland Tomatoes” or that a woman semi-fluent in English would write about Susan B. Anthony that “even the suffragette has her liking for gastronomic pleasures.”

The irony is that in the more than seven months of recipe-sharing, Chicken Tetrazzini never made an appearance.

The dish Luisa named after herself (and which she independently confirmed to an Australian reporter as her creation) was “Filet Mignons a la Tetrazzini.” A bit more elevated and befitting of an opera singer living the high life. White truffles, spinach and Parmesan are involved…I can send you the recipe.

Getting Gas Lit (and Guess Where Answer)

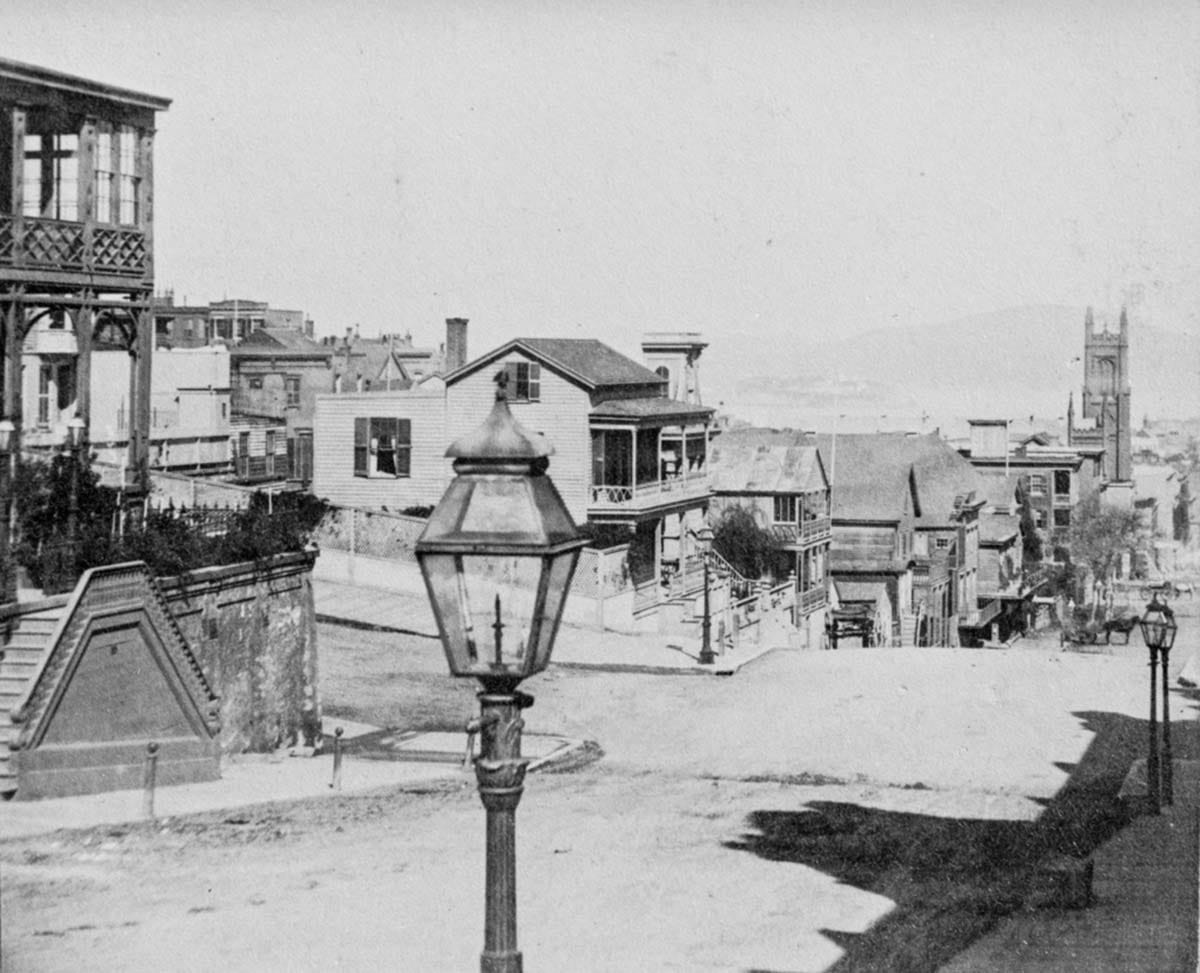

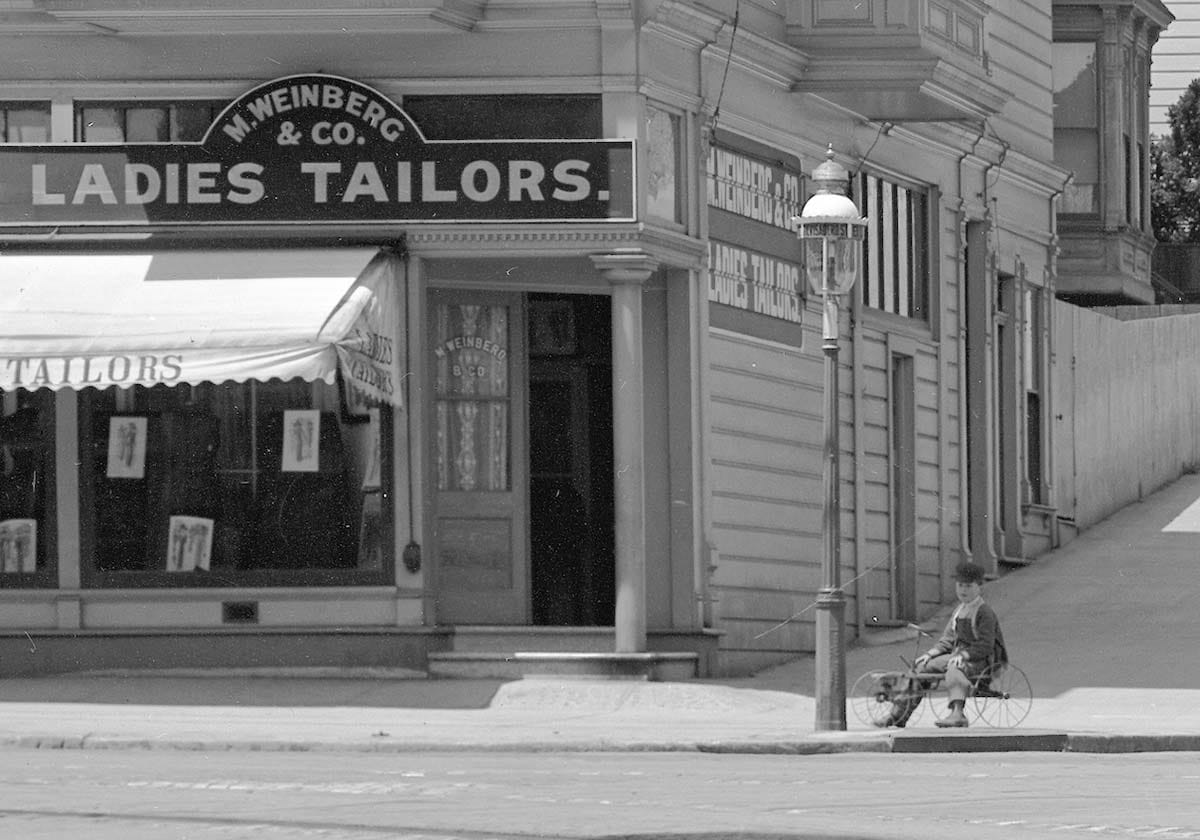

Our Guess Where this week is the handsome Masonic building on the southwest corner of 9th Avenue and Judah Street in the Inner Sunset District. Today it is the Zhong Shu Temple for a Buddhist organization.

Let us talk about that awesome triple-headed gas street light on the corner of the historical photo.

I live in the Richmond District and our good friends at PG&E have had a difficult time keeping the lights on for us over the last month. During some of the recent black-outs the avenues have been mighty dark at night.

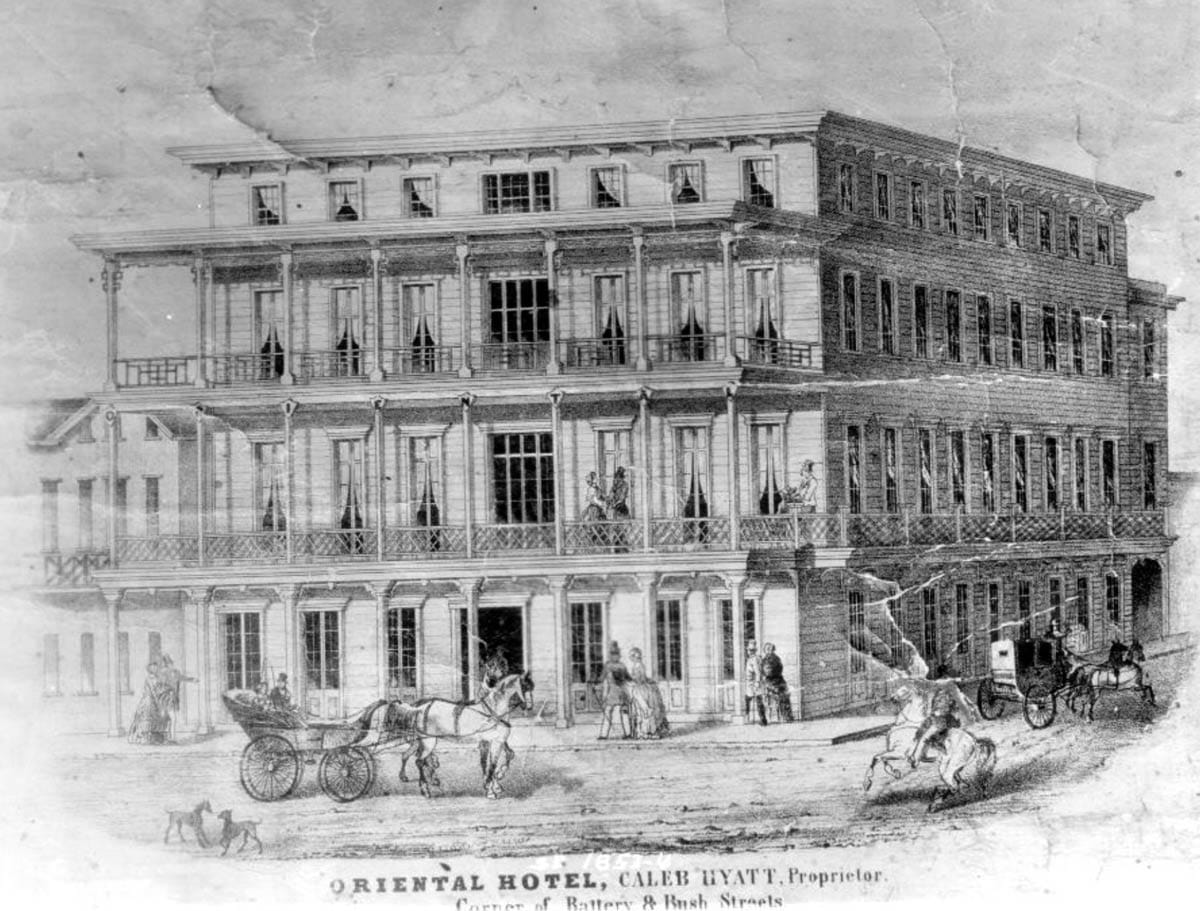

In 1852, just a couple of years after its boom-town beginnings, San Francisco sought to address its dim and often dangerous streets. Some downtown intersections had whale-oil lamps, but city government was keen to install brighter and more reliable gas lamp posts.

The Donahue Brothers won the bidding and formed the San Francisco Gas Company. The first gas lamps—84 of them along Montgomery Street, Kearny Street, today’s Grant Avenue (then Dupont), and parts of Clay, Commercial, and Washington streets—were officially illuminated the evening of February 11, 1854.

Even with a full moon that first night, the Alta noticed the improvement which gas lighting brought: “In traveling over the muddy side-walks and in wading through the street crossings, there was a light ahead which showed the pedestrian how to pick his way, and seemed as a sort of guiding star through the mud.”

Additional income was made by piping gas to private entities and businesses along the illuminated path.

That first night, at the brilliantly lit-up Oriental Hotel, more than two hundred city leaders and captains of industry gathered to celebrate the arrival of gas in San Francisco. A score of drunken toasts were made, the best-considered coming from a newspaper editor to “the ladies of San Francisco, whose eyes only can eclipse the gas [light].”

At the conclusion of the evening the Alta noted the gas lights were probably little help in directing the wobbly, much-affected guests to find their homes.

A Slice of Sutro Baths History

Gary Stark over at the excellent Cliff House History Project recently picked up a souvenir postcard on eBay. He shared it with a group of history colleagues (including me):

This passel of tourists and their guide are posing in front of an eye-catching slice of redwood tree. For years it was affixed beside the entrance to Sutro Baths, just up the hill from the Cliff House, and served as an advertisement of California’s wonders (and Humboldt County):

John Freeman, who has done a lot of research on the different tour guide businesses at the Cliff House, says the redwood-round was used as a photo-taking stop by a company associated with the Billington family, who ran a “while you wait” photo business at Lands End.

Tourist-bus groups got snapped in front of the redwood slice before they visited the Cliff House. While they admired the view and got refreshments above Seal Rocks, the film was processed up the hill. By the time of re-boarding their “rubberneck wagon,” souvenir photo-postcards were ready and waiting for purchase.

There may not have been easily-available aerosol paint cans in the 1910s, but there were pocket knives. A close-up view of the redwood slice reveals more than a few people left their initials:

What happened to the mighty redwood slice? Researcher John Martini tracked it through historical photos up to early 1933. By the time of the cool Art Deco remodel of Sutro Baths entrance the following year, the old giant was gone.

Can we talk briefly about that beautiful woman’s hat?

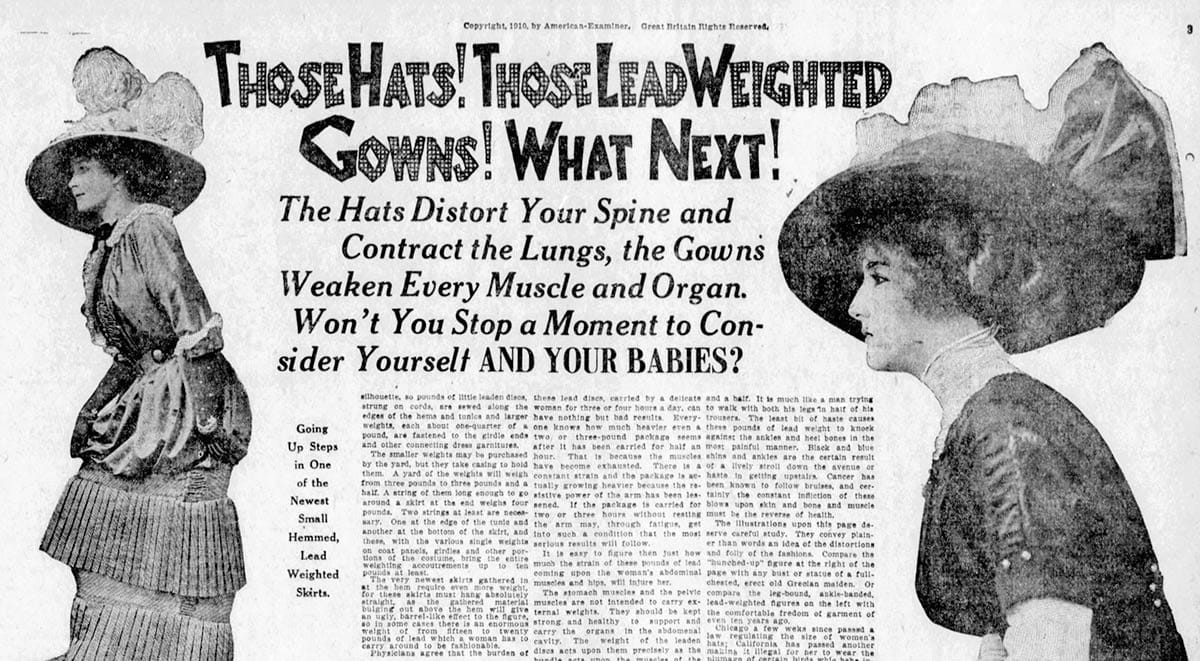

Consider Your Babies

In the late 1900s and early 1910s, women’s fashion took one of its extreme left-turns.

I am not an expert on the subject, but there are plenty of degree and doctoral programs on how patriarchal societies control and pressure women into ridiculously restrictive and occasionally exuberant outfits. The years just before World War I were real doozies, especially for hats.

The script is always the same. When newspapers and taste-makers have pushed everyone into the latest look, they turn around and shame women for their vanity, foolishness, and abdication of their proper roles as wives and mothers. Here’s a great example from 1910:

All that said, you all know, I am a fan of a hats. I almost root for the cruel wheel of fashion to spin back to the days of millinery and haberdashers.

Last Gas(p)

After its 1852 introduction in San Francisco, gas-lamp technology was improved over time. The early lamp posts had boxy lanterns and, on the shafts, small extended arms for lamplighters to lean their ladders against.

Each night the lamps had to be lighted and each morning doused. The job evolved into one similar to boys’ paper routes in the 20th century. Many a local corporate head humble-bragged that he started his career as a lamp lighter.

A switch was later invented to save lugging a ladder around. By the turn of the century, rounded glass enclosures which better spread and directed illumination became the norm.

In 1905, the Pacific Gas and Electric monopoly we know today began buying up smaller companies. Electricity had already been introduced as the latest street-lighting marvel—Market Street and other important thoroughfares downtown had electric lights in the 1880s—but thousands of streets were still piped with gas at the time of the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The transition away from gas accelerated during the city’s rebuilding, but thousands of lamp posts in the Mission District, Western Addition, and outlying neighborhoods remained in service for another quarter of a century.

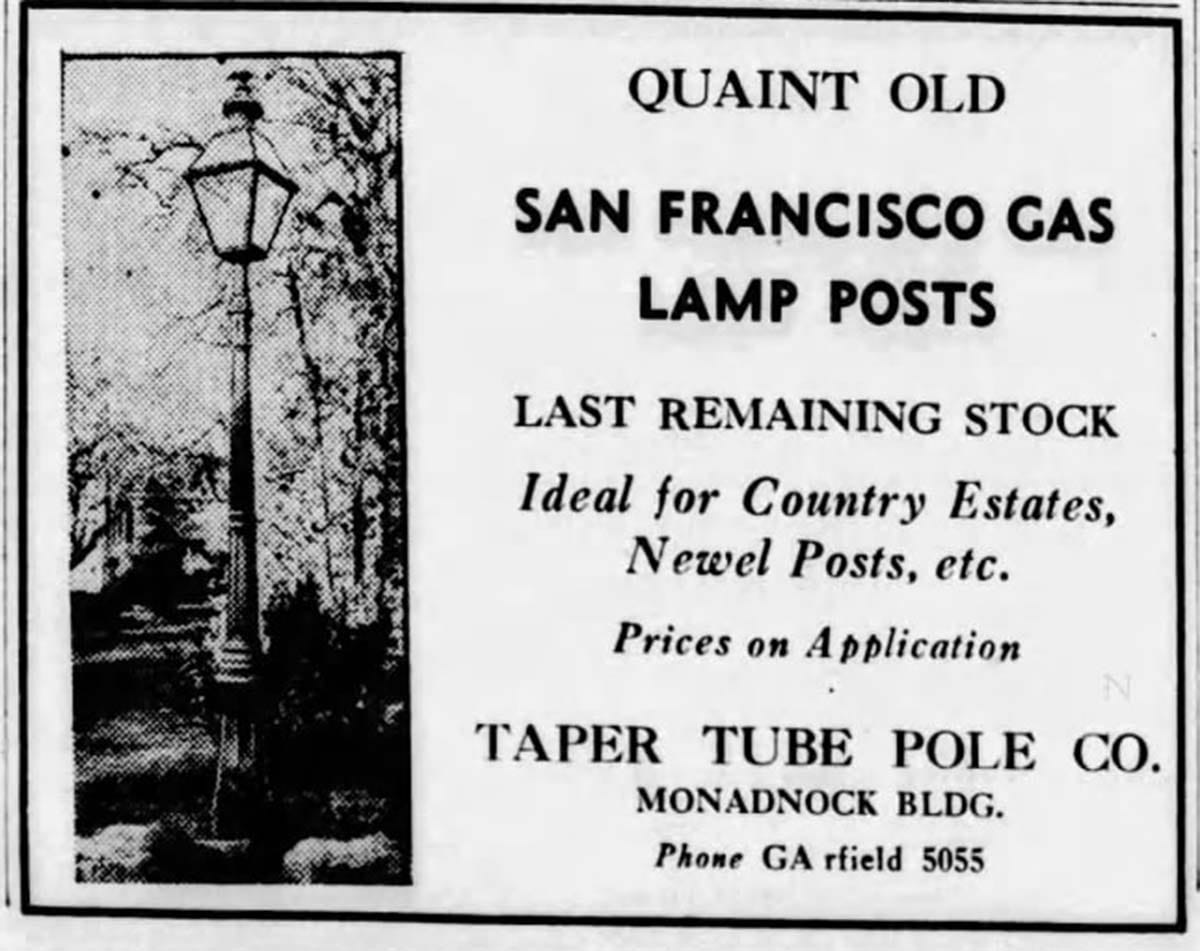

Finally, in 1929, a modernization push by the board of supervisors directed PG&E to transition all street lighting to electricity, a job that was completed the following year.

There was almost instant nostalgia for the soft gas light. Owners of country estates grabbed many of the old lamp posts. A developer in Menlo Park recycled (but electrified) 14 of them for a housing project.

Gas made a small comeback when a retro movement for Victorian design arose in the mid 1960s. For more than a decade, in fern bars, historical restaurants, and public parks like the Hyde Street cable car turnaround, gas lamps were reintroduced to give an antique-y flavor.

Upwardly mobile homeowners who were restoring Victorian homes put in gas and even sidewalk lamp posts. You can see a couple in front of 1810-1812 Scott Street, installed by Robert Olson in 1964:

A stranger survivor is up the hill in the yard of 200 Euclid Avenue at the corner of Laurel Street in Laurel Heights. It is a true historical San Francisco street lamp, just slightly cut down, but retaining its signature cap and twisted iron pole:

Laurel Hill Cemetery occupied this whole hillside until the late 1930s. Aerial views of the cemetery don’t show a street lamp in the vicinity. The house at 200 Euclid Street wasn’t constructed until 1948.

The current owner, Peter, doesn’t know who put the post in before him or when it happened. Maybe some reader does?

Despite being wired and having a small yellow bulb visible inside, the lamp doesn’t seem to work, so we might label this survivor another San Francisco “Thomasson.” (Scroll to the end of Grab Bag #45 for the definition.)

Enough gas from me. See you next week.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Thanks to Stephanie S. (F.O.W. from waaayy back) for contributing to the over-capitalized Woody Beer and Coffee Fund. Let me know when you can meet and let me buy you a beverage. Make it your New Year’s resolution!

Sources

“San Francisco by Gas-Light,” Daily Alta California, February 12, 1854, pg. 2.

“Tetrazzini Cooking,” Daily Mercury (Mackay, Queensland, Australia), February 7, 1910, pg. 7.

Fannie Merritt Farmer, “My Best Chicken Recipes,” Woman’s Home Companion, September 1909, pg. 56.

Luisa Tetrazzini, “Dishes Great Folk Liked,” San Francisco Examiner, May 29, 1910, American Magazine Section, pg. 11.

“Gas Lamps Sought by Curio Collectors,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 10, 1931, pg. 6.

Richard Thierot, “The Lights That Failed,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 29, 1964, pg. 5.