Living Off the Grid

San Francisco's 1840s Laguna Survey gave the city some growing pains

San Francisco’s first official western boundary was Larkin Street…mostly.

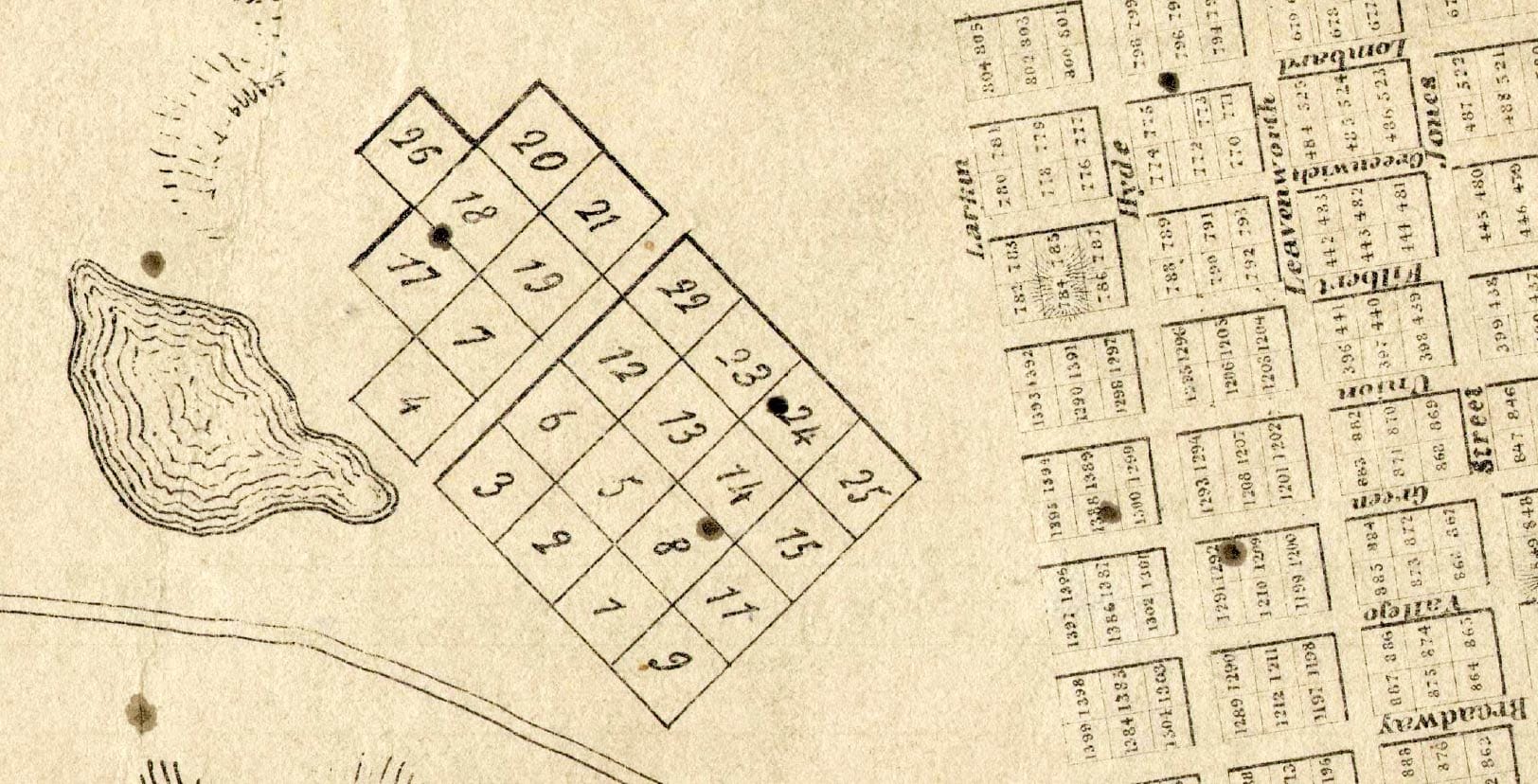

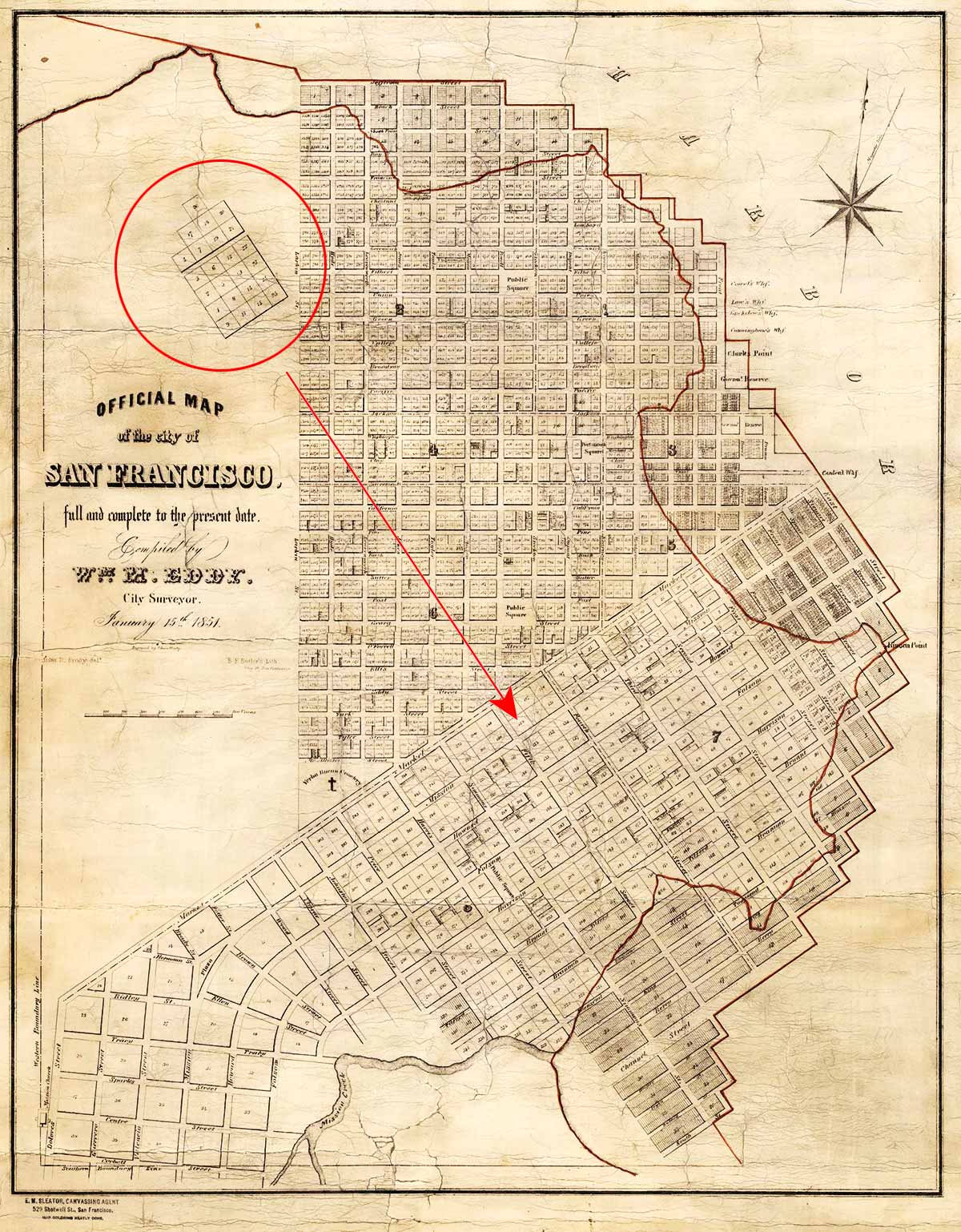

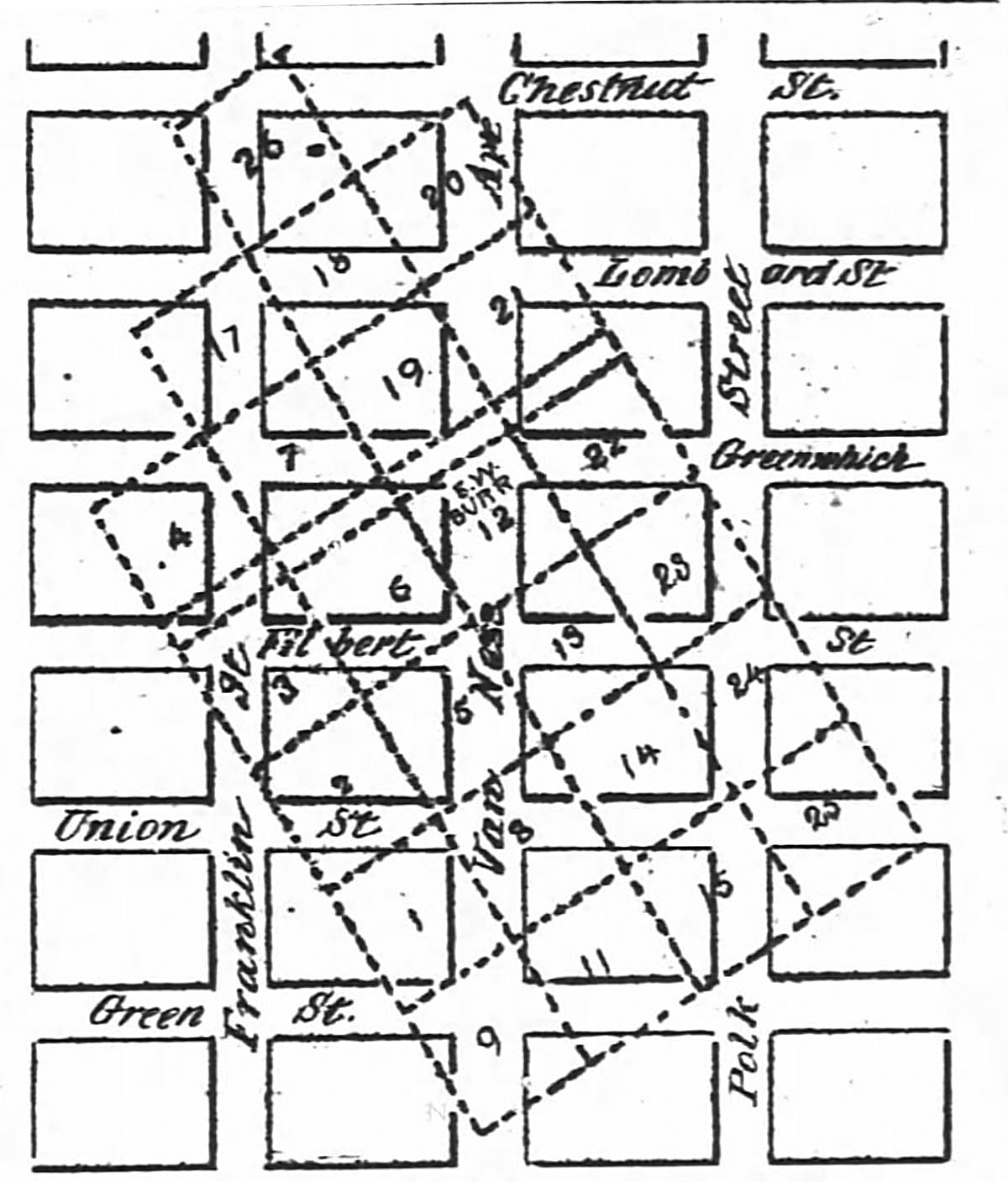

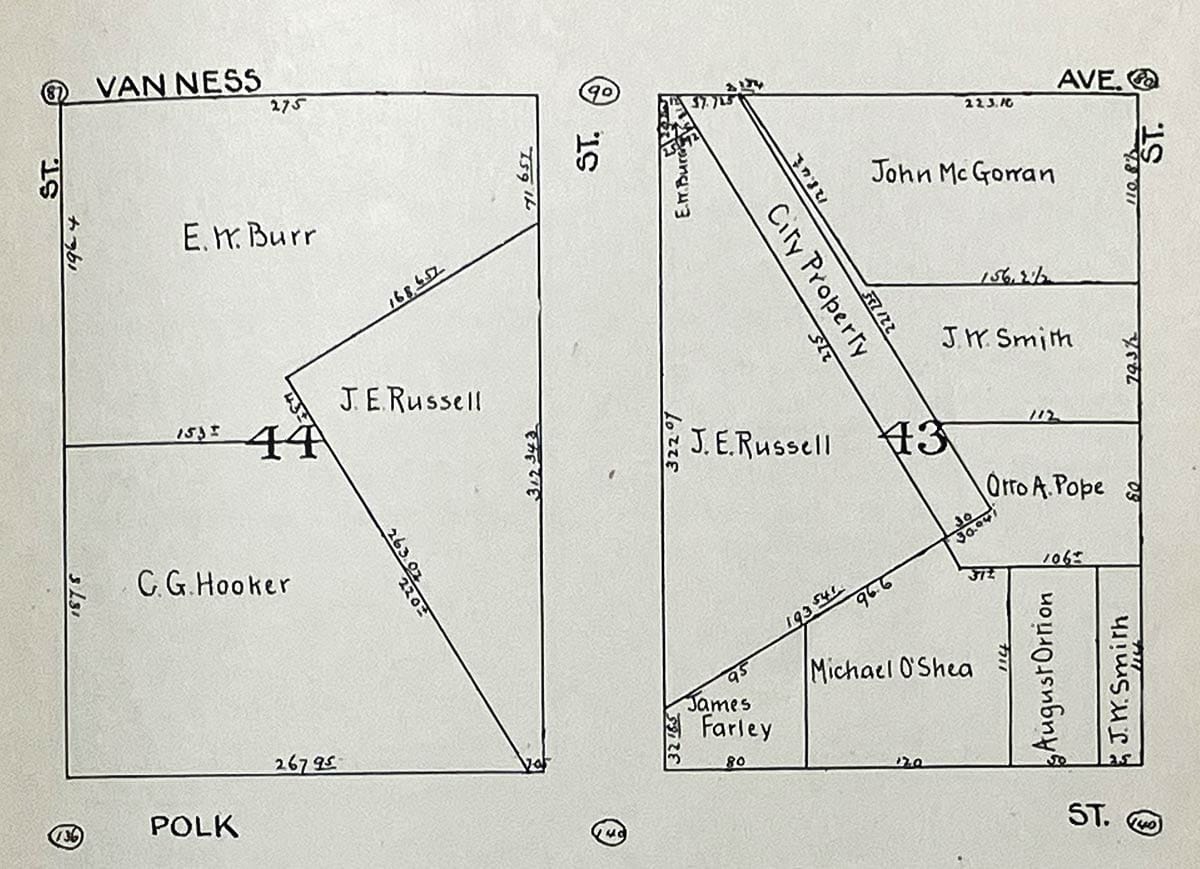

On early maps is a strange exception, a loose puzzle piece made up of 24 parcels on the western slope of Russian Hill lying at an adjacent angle just beyond the city’s orderly grid pattern:

These 100-vara blocks (275-feet-by-275-feet) were surveyed next to a large pond known as Washerwoman’s Lagoon, namesake of Laguna Street. The lots were sized and set on the alignment of blocks that surveyor Jasper O’Farrell drew up for the city’s land south of Market Street.

Alcades George Hyde and William Leavenworth (there are some more street-name sources for you) doled out lagoon survey plots to grantees between December 1847 and March 1849, just after the United States conquered California and just before all the Gold Rush craziness turned pueblo Yerba Buena into the boom town of San Francisco.*

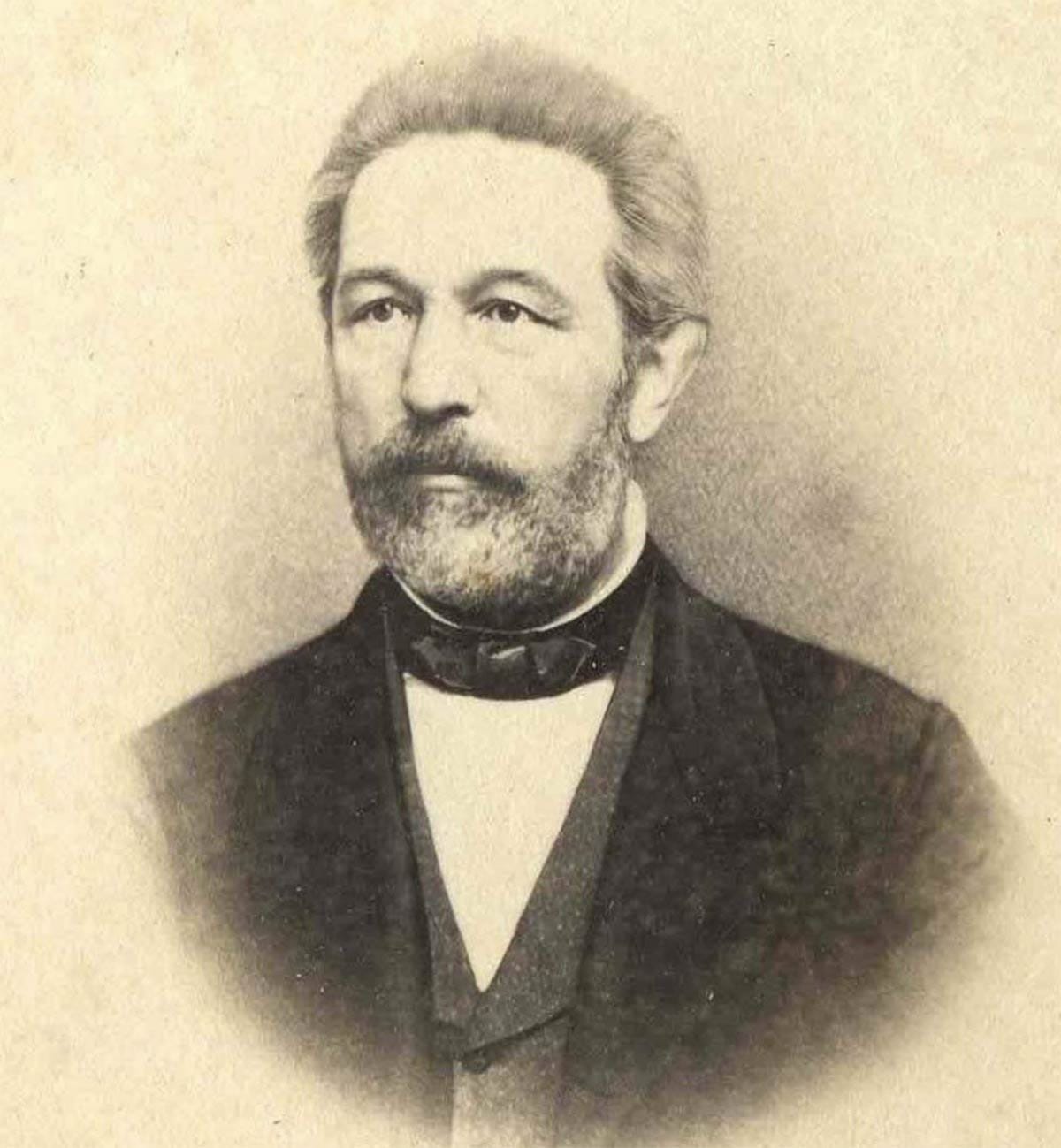

One of those Gold Rushers, Ephraim W. Burr, made a small fortune in the wholesale grocery business and after two years in California sent for his wife, Abby, and five children to join him from back east.

The Burrs ended up buying lot #13 of the Laguna Survey because Abby didn’t want to live in “the middle of sand dunes” and liked the view of the Golden Gate.

In July 1852, Burr put an ad in the newspapers seeking a builder for a “cottage house,” a prefabricated kit shipped from the Atlantic seaboard. In 1853, this cottage was described in an ad for an adjoining lot as a “splendid brick mansion” surrounded by gardens. (The brick part was likely a mischaracterization.)

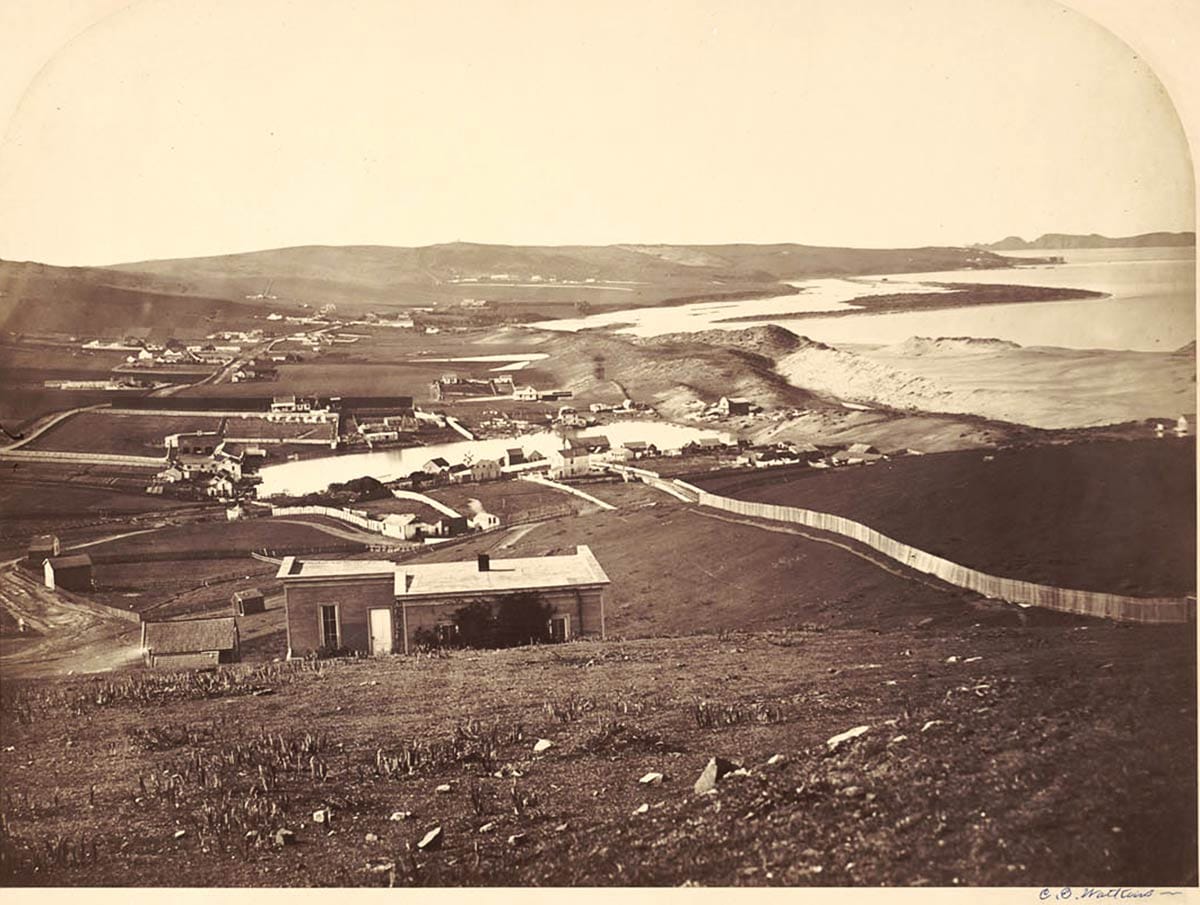

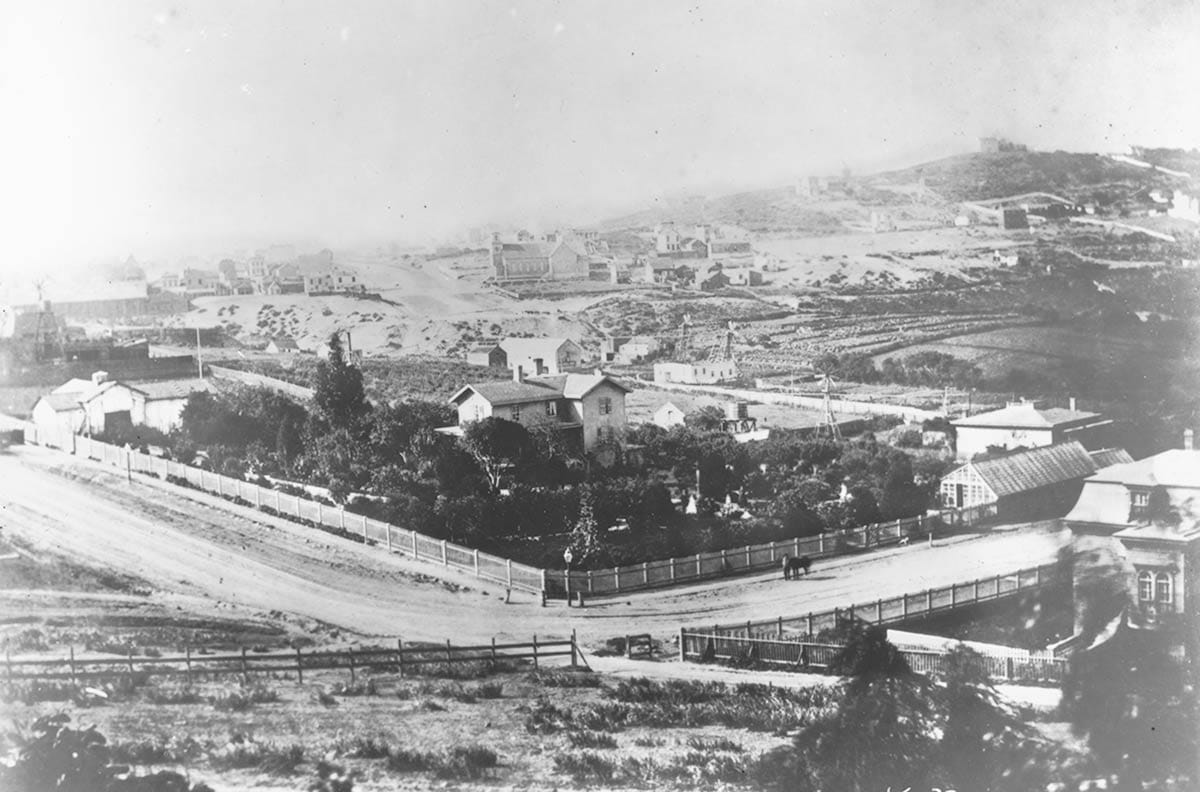

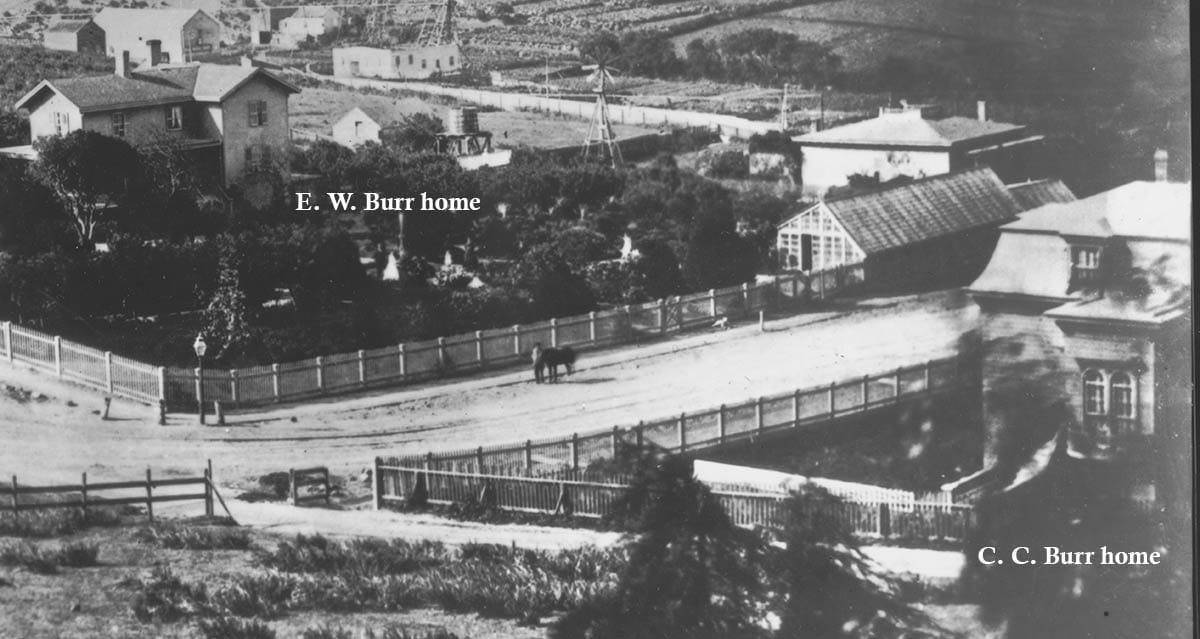

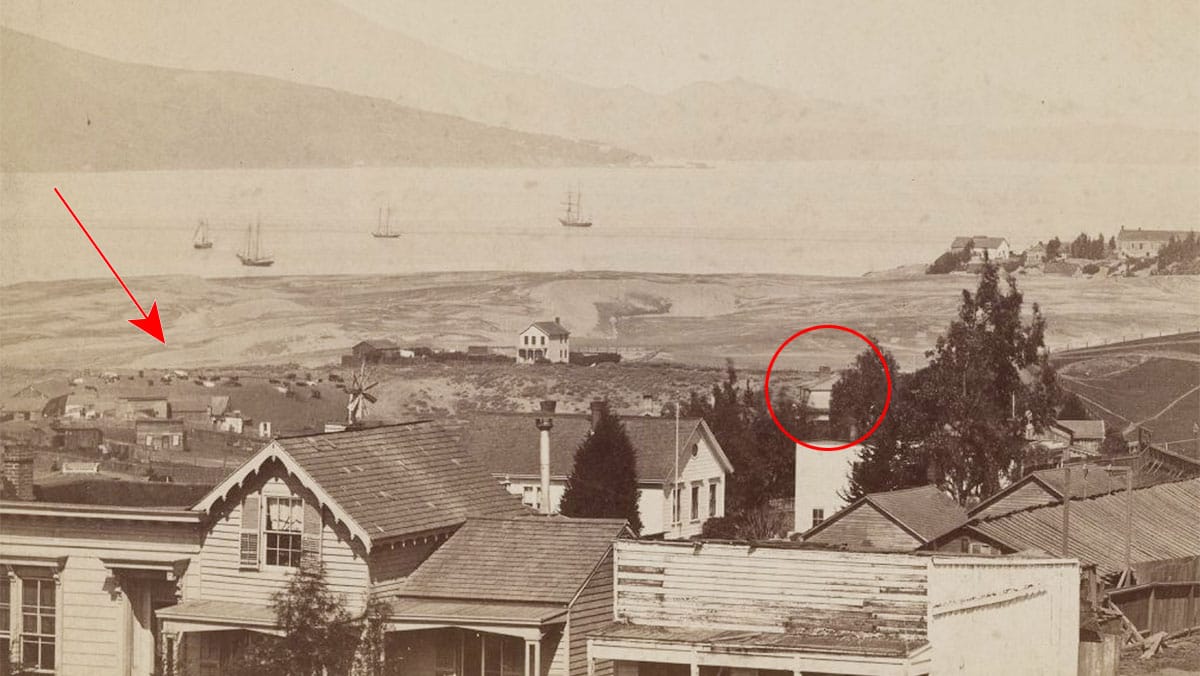

Here’s an 1870s view of the Burr home and gardens that deserves some examination:

We’re looking southwest from roughly today’s Greenwich and Polk Streets on Russian Hill. In the distance is an early version of St. Brigid’s Church on the southwest corner of Van Ness Avenue and Broadway. The hill is where Lafayette Square park is today.

While looking like a proper city intersection in the foreground, that road bordering the Burr property was a right-of-way granted to an early horse-car line to reach lands west. Rails are faintly visible.

After starting in the grocery business, E. W. Burr did well in banking and, for a short time, politics. In 1856, he was put up as a candidate for mayor by one of the city’s vigilante movements. He won and served in the office from 1856 to 1859.

His son, Clarence C. Burr built his own mansion across the right-of-way from his father. It’s visible on the right edge of the photo and was later addressed 1456 Filbert Street.

At the time, Van Ness Avenue dead-ended at about Vallejo Street, stymied by a tall sand bank.

It was also blocked by the awkward Laguna Survey blocks, which didn’t line up with the city’s expanding grid pattern from downtown.

Owners like Burr were not going to hand over chunks of their land for city streets without significant compensation. City taxpayers balked at the first offer in the 1870s ($700,000) and the impasse, in principal and physically on streets like Van Ness Avenue, lasted a lot longer than you might think.

Life in Spring Valley

Washerwoman’s Lagoon was fed by a spring from up the hill at Pacific Avenue and Larkin Street.

An effusive correspondent in 1851 called the “Spring Valley” area a “delightful suburb,” noting “pure and healthful air” combined with “beauty of scenery surpassed by few places in California.”

Fresh water was like gold in boom town days and both the spring and the lagoon were intensively exploited. The spring’s head became the site of slaughterhouses.

The same issue of the same newspaper which extolled Spring Valley’s “pure and healthful” air in 1851 also contained a short item about an abattoir at Pacific and Larkin:

“The stench is awful […] The amount of cattle’s heads, skins and offal, heaped up in and about this concern, in every stage of decay, contaminating the atmosphere for a long distance, is beyond belief.”

The lagoon, separated from the bay by a ridge of sand dunes, became home to laundries and tanneries, while the fertile soil surrounding it was cultivated for agriculture and used by dairies with the namesake herds of today’s Cow Hollow neighborhood.

Some property owners like Burr used windmills, water tanks, and cisterns for their water needs, but their proximity to the blood, gore, and manure of neighboring industries did not make for healthful conditions.

Burr lost a son, William C. Burr, to cholera in 1855, and was instrumental in convincing the city to banish some of the uphill animal operations.

End of Lagoon and Laguna Survey

The lagoon was filled in the 1880s. The city and Laguna Survey owners finally reached some agreement on extending streets through Spring Valley in 1891.

“The prospects are very favorable for the complete blotting out of the Laguna survey,” wrote a Chronicle reporter at the time, “and in future maps it will only be a thing for historical reference.”

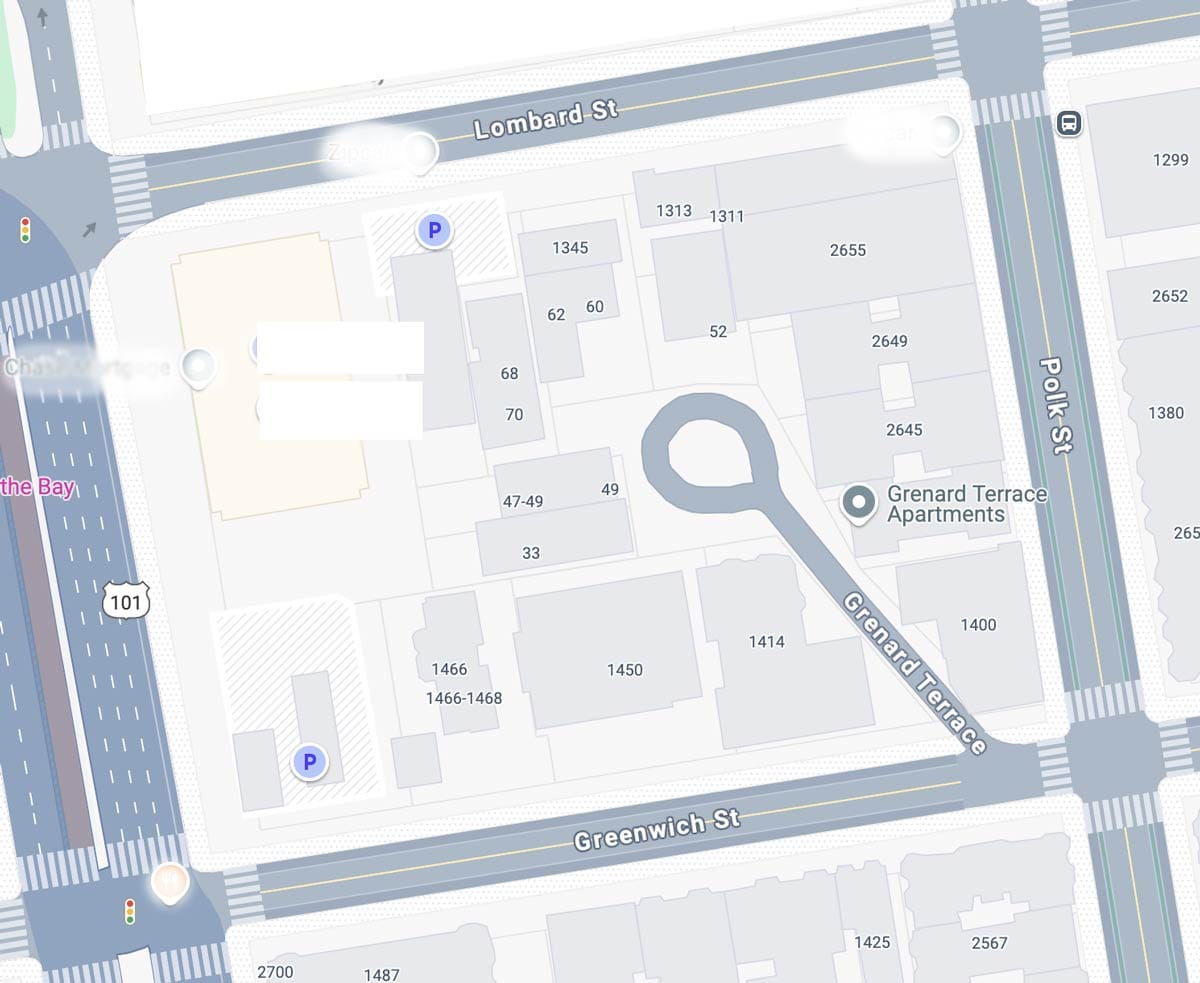

And so it is, although for a long time the Laguna Survey made for some odd property lines within city blocks:

Grenard Terrace, a diagonal stub of street off Greenwich near Polk, is a surviving artifact of the old Laguna Survey lines, and I think some of the off-kilter facades of Van Ness Avenue apartment buildings may be legacies as well.

The Last Burr to Leave

E. W. Burr died in 1894 and was buried at Cypress Lawn cemetery in today’s city of Colma.

In 1906, the gardens around the old family house and the dynamiting of the pioneer mansion helped make a firebreak against the maelstrom rushing up Van Ness Avenue after the April 18 earthquake. The flames swerved east, just short of C. C. Burr’s house on Filbert Street, and moved over Russian Hill to North Beach.

An apartment building was built on the E. W. Burr plot in the rebuilding after the 1906 disaster and his son’s place on Filbert Street was turned into a tenement house after C. C. Burr died in 1917.

In 1927, 1456 Filbert was demolished to make way for a six-story 73-unit apartment building.

In the late 1950s, Van Ness Avenue had become a California state highway filled with automobile showrooms and new big motels. Public memory of the E. W. Burr homestead had faded with the Laguna Survey, the lagoon itself, the vegetable gardens, the windmills, and the countryside views.

The Continental Lodge, a 200-unit motel, replaced the apartments on Burr’s old land in 1958. Business was so good that the inn owners began an expansion up the hill in 1960.

During excavation they discovered a water cistern with a helpful date inscribed at its top:

I haven’t been able to find much on this discovery beyond a brief mention in Dick Nolan’s gossip column in the San Francisco Examiner, a quote which adds an eye-opening detail deserving more investigation:

“Workmen excavating for a 100-room addition to the Continental Lodge uncovered a couple of relics the other day. A 1,000 gallon cistern dated 1859, and a long forgotten casket unidentifiable…”

Willard C. Burr, the son who died from cholera in 1855, was buried at Lone Mountain Cemetery. So whose remains did the casket hold?

Unknown, but it seems that while you may live and even die off the grid, sometime or another the world may still find you.

*Officially, the name change happened in January 1847, but in spirit...

Great thanks to Martine Darwish and Robert Bardell for all their research on the area.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Much appreciation to Lisa B. and Gabe E. (F.O.W) for contributing to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund, perhaps the most impactful entity for my hydration and social well-being. I owe some of you drink-dates. Check your email, as I finally got back to you last night!

Hey, the rest of you, when are you free to have me treat you to a beverage?

Sources

“Spring Valley” and “Abate the Nuisance,” The Steamer Pacific News, May 15, 1851, pg. 2.

“To Builders,” Daily Alta California, July 29, 1852, pg. 2.

“Valuable Property for Sale,” Daily Alta California, February 8, 1853, pg. 3.

Real Estate sales, Daily Alta California, March 1, 1853, pg. 3

“The Laguna Survey,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 17, 1891, pg.

Dick Nolan, “The City,” San Francisco Examiner, July 5, 1960, Section 3, pg. 1.

John L. Levinsohn, Cow Hollow: Early Days of a San Francisco Neighborhood from 1776 (San Francisco: San Francisco Yesterday, 1976)

Ilza M. Hakenen, “Ephraim Willard Burr: A California Pioneer” (Thesis, M.S.S., Humboldt State University, August 2008)

Robert Bardell, “The Presidio Road,” unpublished manuscript, circa 2012. (Bob had also had an edited article on the topic published in the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society’s journal, The Argonaut.)

Gary Kamiya has also been here (as he has in most San Francisco history places): San Francisco's Off-Kilter First Suburb