A Day Trip on the Mission Road, Part 1

In the 1850s, San Francisco Sunday recreation meant getting across sand dunes and marsh to the Mission.

Let's head back to the days when people worked downtown—("2019?" No, earlier.)—and see what fun we can have in the Mission District—("Is the Elbo Room still open?" No, earlier that that.). We're going back to the 1850s.

Before Mr. Peabody sets the way-back machine, note that the next two San Francisco Story emails aren't about the history of the Mission, the Mission system, or the real horrors of colonialism to the native people who lived here. I am not trying to gloss over genocide or romanticize history, but just focus on one hedonistic slice of the city’s past. We are playing the parts of mostly clueless Americans looking for a good time, not unlike many of the bros you saw on Valencia Street last Saturday.

This week we're just going to try to get to the Mission. Next week we'll party like it's 1869. OK, let's get started:

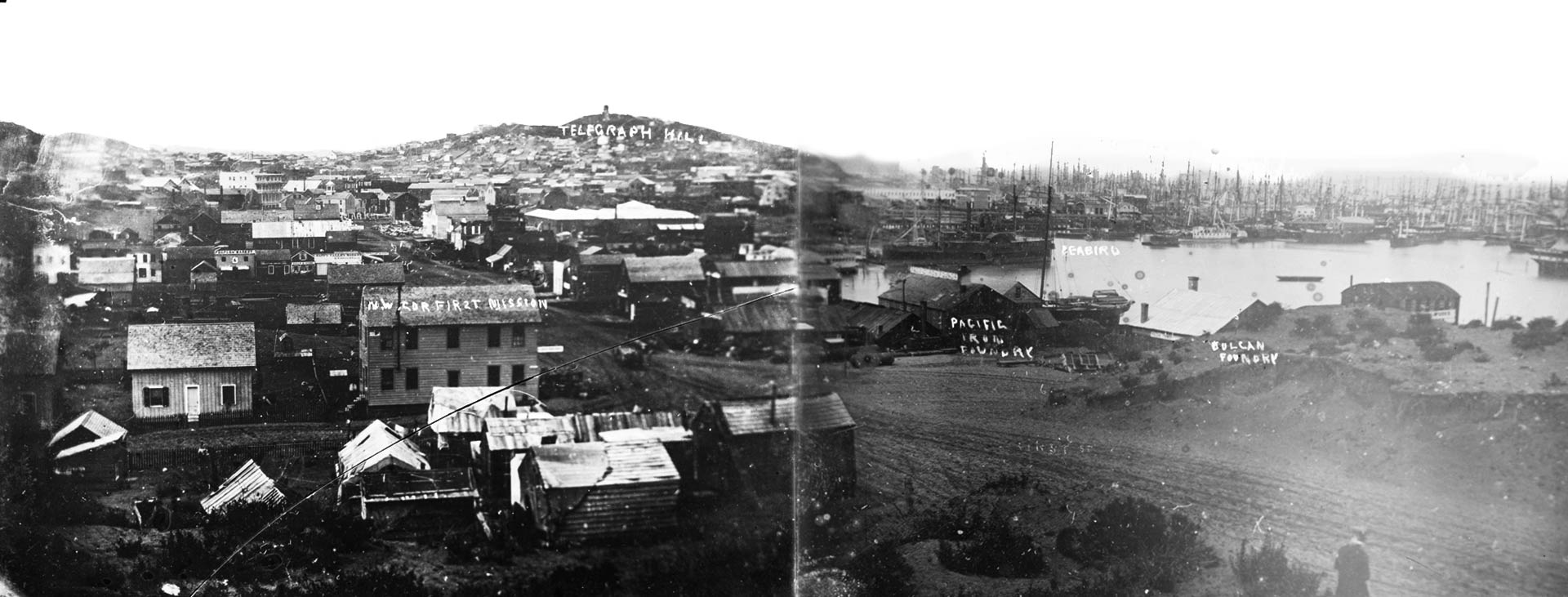

1st and Mission Streets, 1851

Here's the young city of San Francisco, a bit wrung out from the Gold Rush. First Street runs right along Yerba Buena Cove, which still has a lot of abandoned ships in the distance and awaits filling in so we can someday build the Millennium and Salesforce towers on the muck.

Let's say we work in one of those foundries on the water and live in one of those sand-flea-infested shacks in the foreground. Where can we go for a bit of fresh air and innocent (or not) recreation?

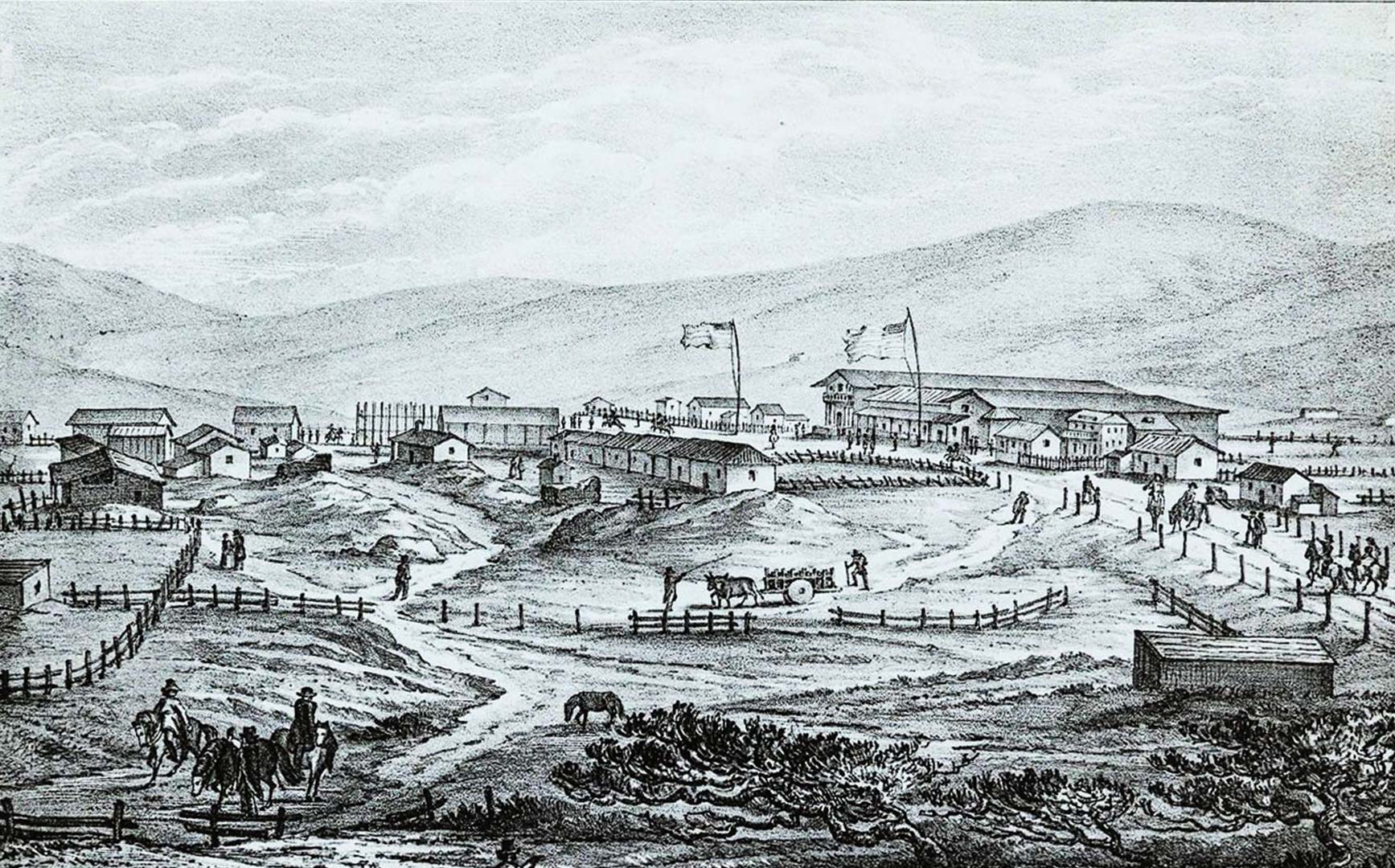

Mission Dolores, 1850s

Ah, bucolic Mission Dolores. Here we are about three miles away from 1st and Mission, 1.5 miles from the western edge of the city limits at the time. This is the countryside. The path reaching it is “a winding way among the sand-hills and chaparral.” The Mission’s weather, soil, and proximity to Mission creek made it the nearest agricultural area for the sandy port of Yerba Buena, with produce carted over the dunes or rafted out of Mission Bay. And there's entertainment options...

Mansion House

The Mansion House looked nothing like a mansion and very little like a house, but it was a place to get a good Milk punch (made of whiskey, milk, and spices). The bar occupied a long single story adobe abutting the north side of the mission church, and part of it had formerly been used as a convent.

Robert T. Ridley (whom everyone called Bob) and his partner Charles V. Stuart (whom everyone called Charley) took over the old adobe in 1850 to quench thirsts of the newly arrived gold-seekers. But we have a problem with the Mansion House. As one man remembered: “in the early days a vehicle was rarely seen there, as, owing to the absence of roads and the abundance of sand, the vicinity could hardly be reached except on horseback.” So how are we going to get there?

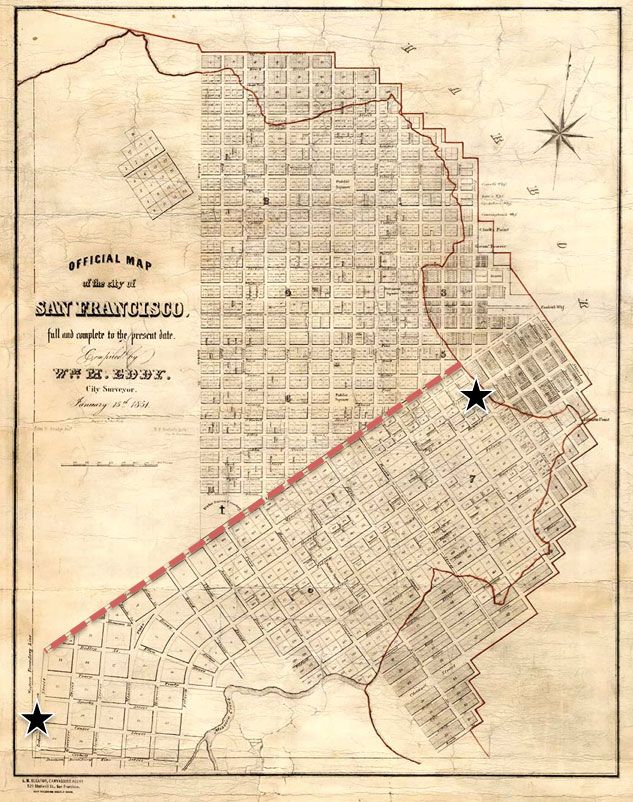

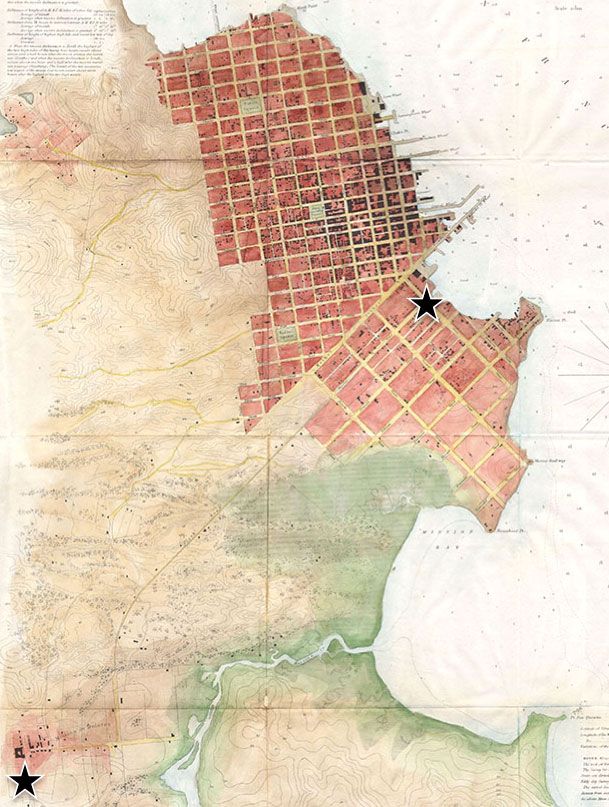

1851 San Francisco Map

Here's the 1851 map of San Francisco, which is 1/2 reality and 1/2 high hopes, as we'll see. The black star I placed on the right is our starting place at 1st and Mission and the left star represents our destination, the Mission. The city's new big avenue is Market Street, which I have highlighted with a red dashed line. So, just get on that, make a left at Dolores Street and —boom—you're there, right? Let's take a look at an 1850s photograph to find out.

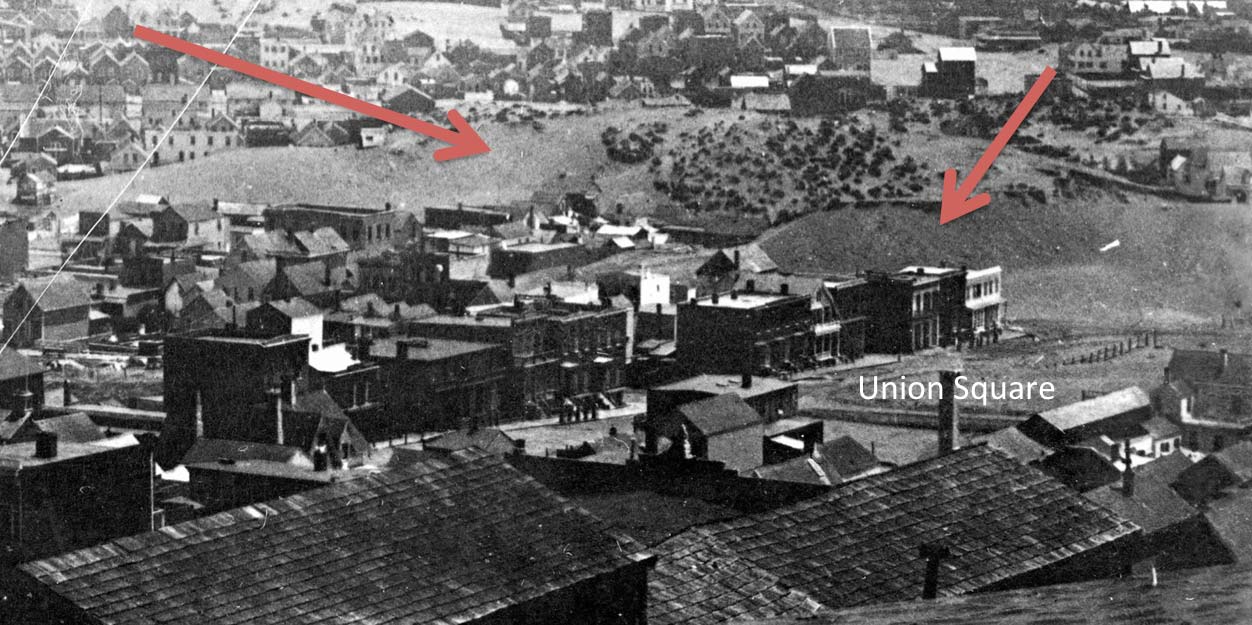

View from Nob Hill, circa 1858

Son, back in the 1850s, before the Chase Center, biotech, and Gus's Market, Mission Bay was a real bay, as you can see in the right distance. But what’s going on inside that yellow square? Let’s take a closer look:

Sand Hill blocking Market Street

That's today's Union Square in the lower right. The left arrow points to a giant sand hill blocking Market Street bet 3rd and 4th Streets. The right arrow marks one blocking Stockton Street between O’Farrell and Geary Streets. Can't trust some maps, man. We can’t go out Market. But there is a road. Let's get a better map.

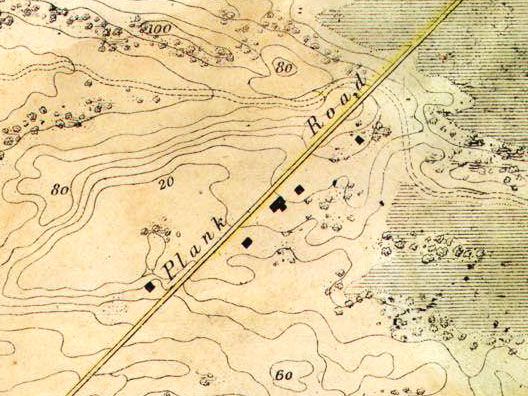

1853 U.S. Coast Survey Map

Here's part of the US Coast Survey map from 1853. I put our happy little stars on 1st and Mission (upper right) and at Mission Dolores (lower left). Unlike the 1851 map, this one shows what’s actually what. Each black dot is a real building. And we can see the completed roads. The bays are bays and most of South of Market is a marshy wetland. Market Street is stymied by those sand hills, but we can see a line arcing southwest through the dunes to just east of the Mission. Let's zero in on the center:

Plank Road! In 1850, Colonel Charles L. Wilson made a pitch to the new city’s Board of Aldermen (as the supervisors were then known). He would build a plank road across the sand dunes, hillocks, marshes, and creeks between Kearny Street and Mission Dolores. The city would receive two and a half miles of easy riding in exchange for Wilson collecting tolls for a decade. After that, the road would be city property.

The plank road would ease the connection to the agricultural bounty of the Mission area, increase property values along the route, and make for a pleasant riding promenade. The city approved the plan in November 1850—negotiating a shorter franchise time of seven years—and Wilson had the road finished by his deadline five months later. Now we're cooking...

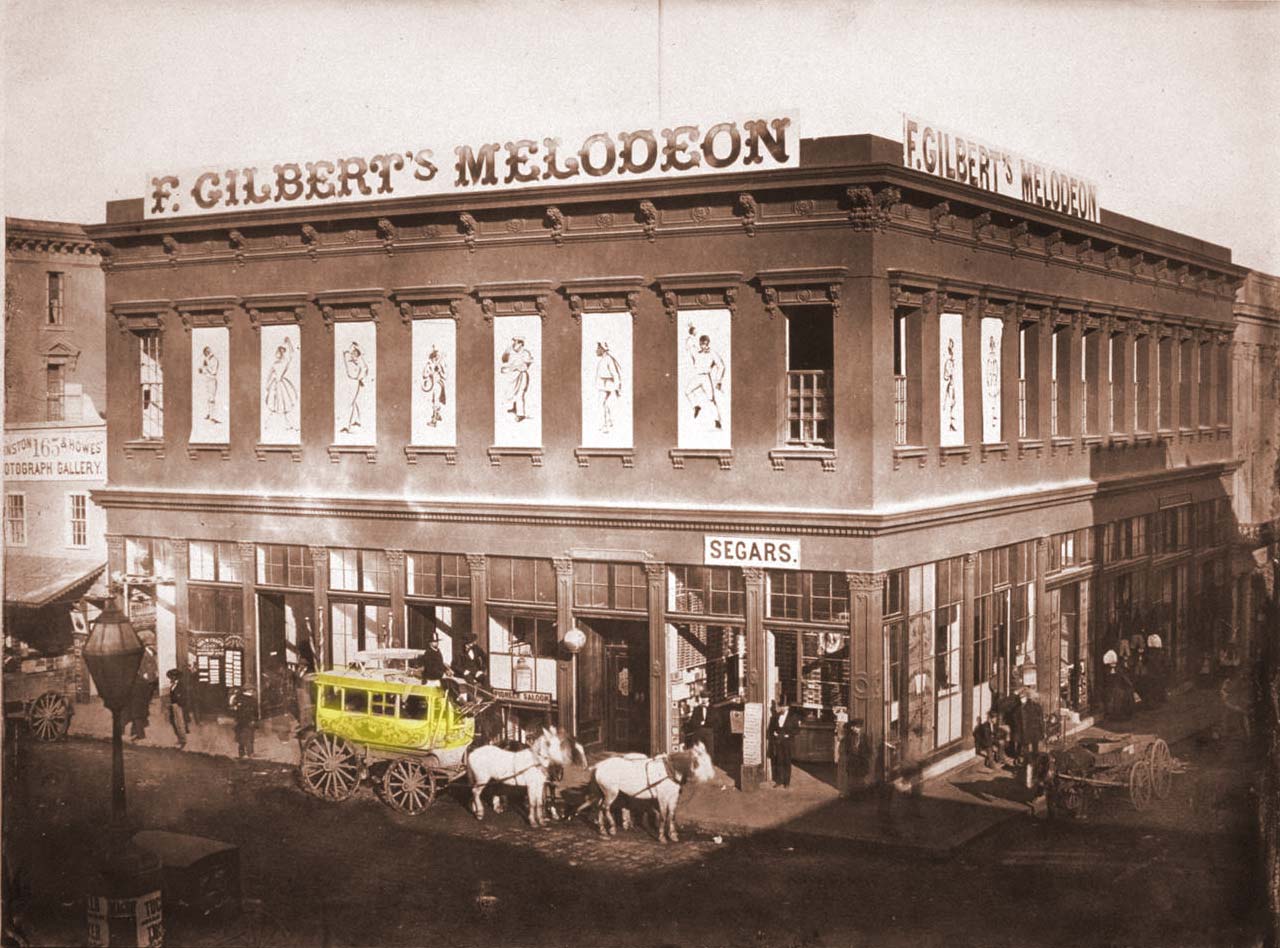

Clay and Kearny Street, circa 1859

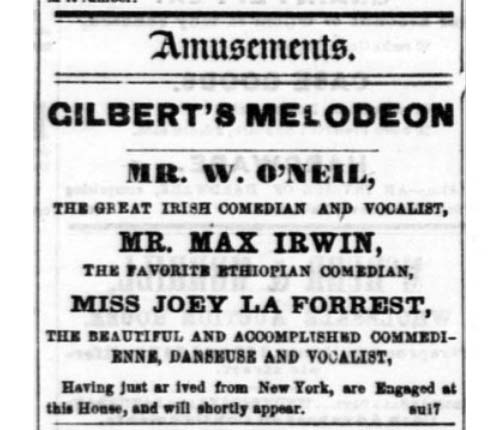

We have a plank road done by May 1851, and by June 1851, omnibus stagecoach lines can take us the whole way on it for a dime. We can catch the “Pioneer” or Yellow line coach, which I have highlighted in crude manner above, at the northeast corner of Clay and Kearny Streets. This was just opposite the center of town then, Portsmouth Square. Let's buy some "segars" to smoke later from the Pioneer saloon, but we are not waiting to see the Irish and Ethiopian comedians upstairs at Gilbert's:

Sunday Entertainments

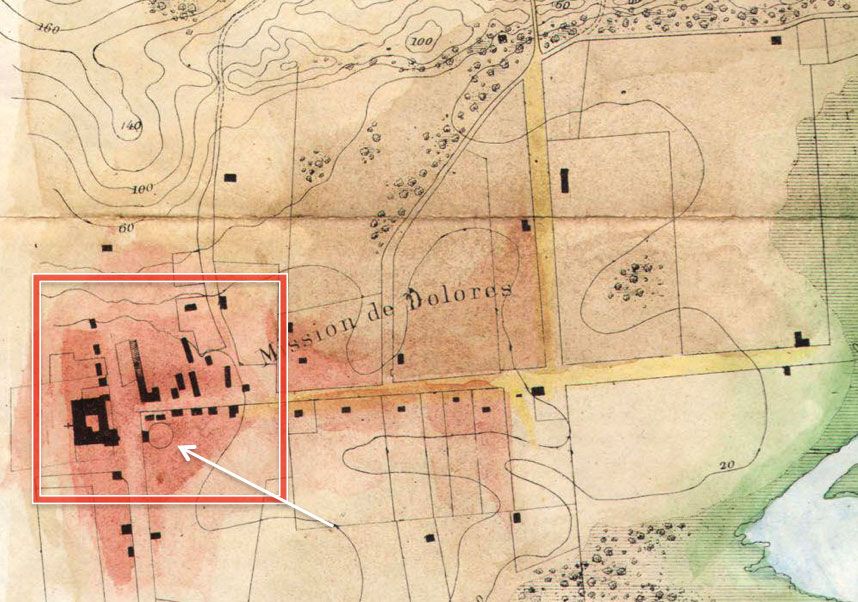

Once we ride out the wooden highway and arrive at the Mission we see another entertainment option right across the road from the church, represented on the 1853 USCS map by a simple circle:

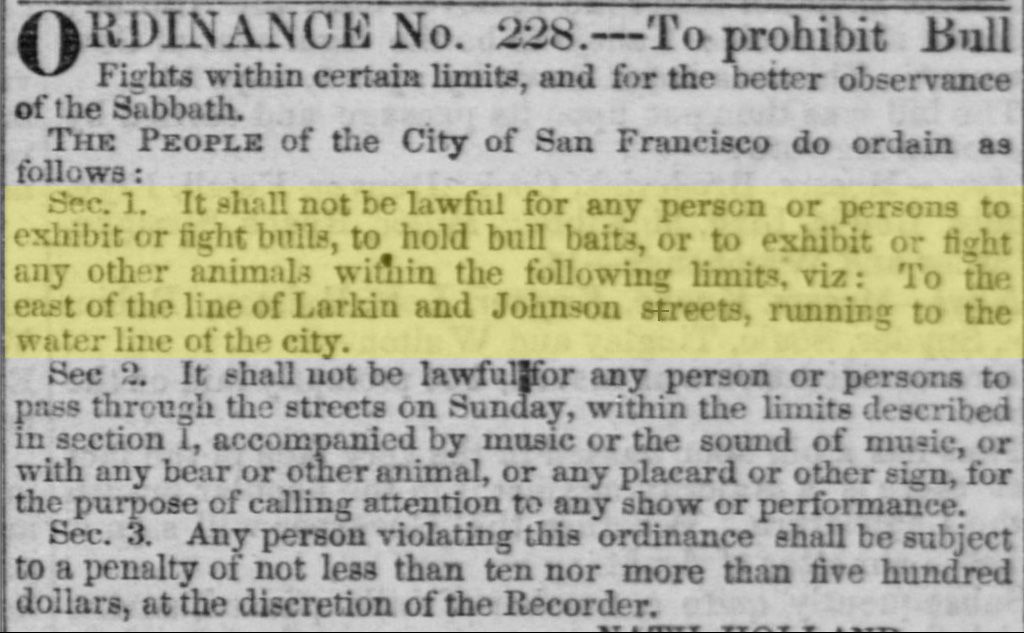

It's a bull ring! The “New Mission Dolores Amphitheatre” had bull fights, bear fights, bulls fighting bears, dogs fighting bulls, bears fighting dogs, people fighting everything. It was a bloody way to spend a Sunday and the city at least kept such vulgarity out of the center of town with an 1852 ordinance:

1858 US Coast Survey Map

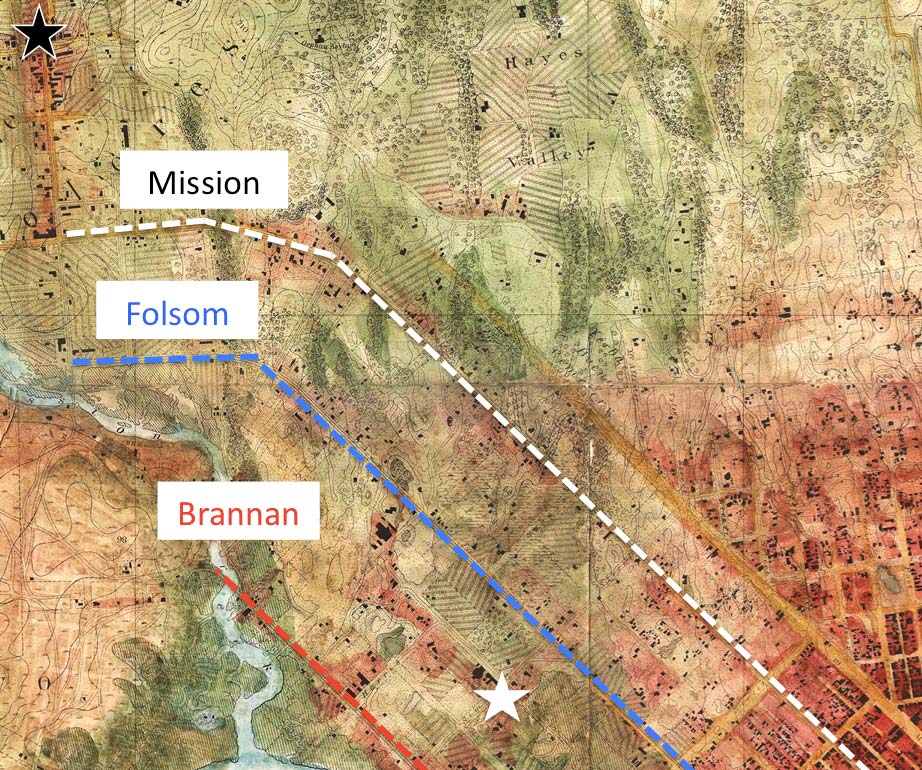

All right, let's jump ahead to 1858, with another accurate US Coast Survey map. North is to the right, West is at the top. Mission Dolores is under the black star in the upper left. And the lower right corner is 3rd and Market Streets. Market Street has fought through the big sand hill, but now peters out a bit short of Hayes Valley at center top.

The Mission plank road was so successful new roads were put in on today's Folsom and Brannan Streets to get you near the pleasures of Mission Dolores, although you have to cross Mission Creek a couple of times on the Brannan route. These roads make it convenient for other bar owners and purveyors of fine viands and recreation to open for business along the way. Between the Folsom and Brannan roads, where I have put a white star, was a popular Sunday picnic spot:

Russ Gardens

When Christian Russ turned his private estate at Harrison and 6th Streets into the public pleasure garden, it became a well known weekend and holiday party site. Situated in what a later writer called “the Wilderness,” Russ Gardens was on a knoll with trees surrounded by a swampy landscape.

It became the haunt of German choruses, bands, and rifle clubs. (There were frequent complaints about the “temerity of the sportsmen” and their poor aim, with occasional shots going through windows of nearby residences.)

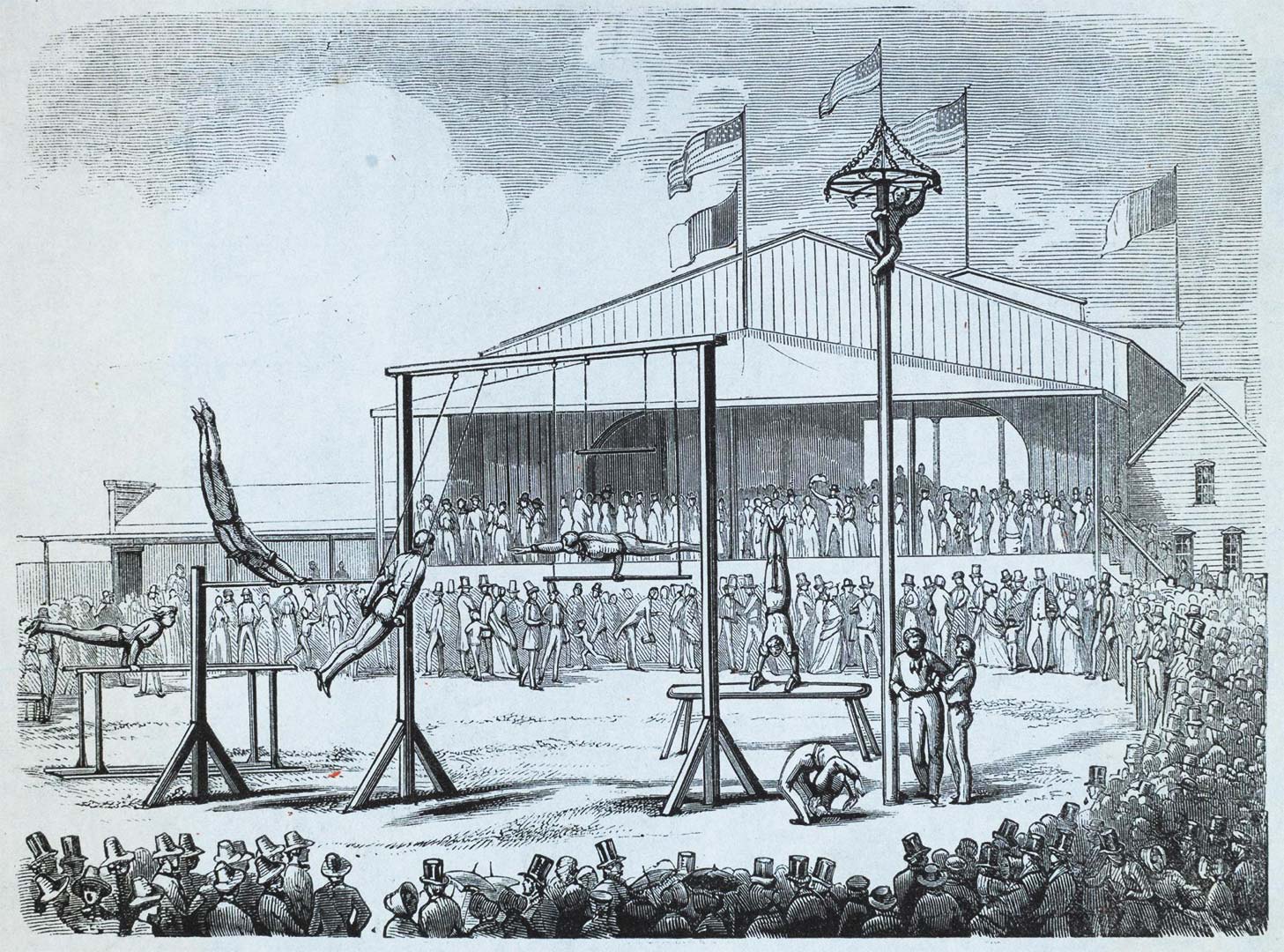

One of the earliest public events at Russ Gardens was a target-shooting tourney in May 1853, in which one of the prizes was a “young grizzly bear.” (That's way worse than your kid winning a goldfish.) There was a nine-pin bowling alley and billiard room. Acrobats and animal acts took over an open-air stage on holidays, and Sunday dances lasted from 10 a.m. until dark in a 150-foot round ballroom. Russ Gardens hosted a two-day festival in 1859 just to commemorate the centennial of writer Friedrich Schiller's birthday. Lots of picnics and beer drinking under trees at long tables.

We're entering a time when women and families braved the entertainments of the Mission Road, so next week we'll take the wife and kids to the Willows, Woodwards Gardens, and more.