Return of the Vigilantes

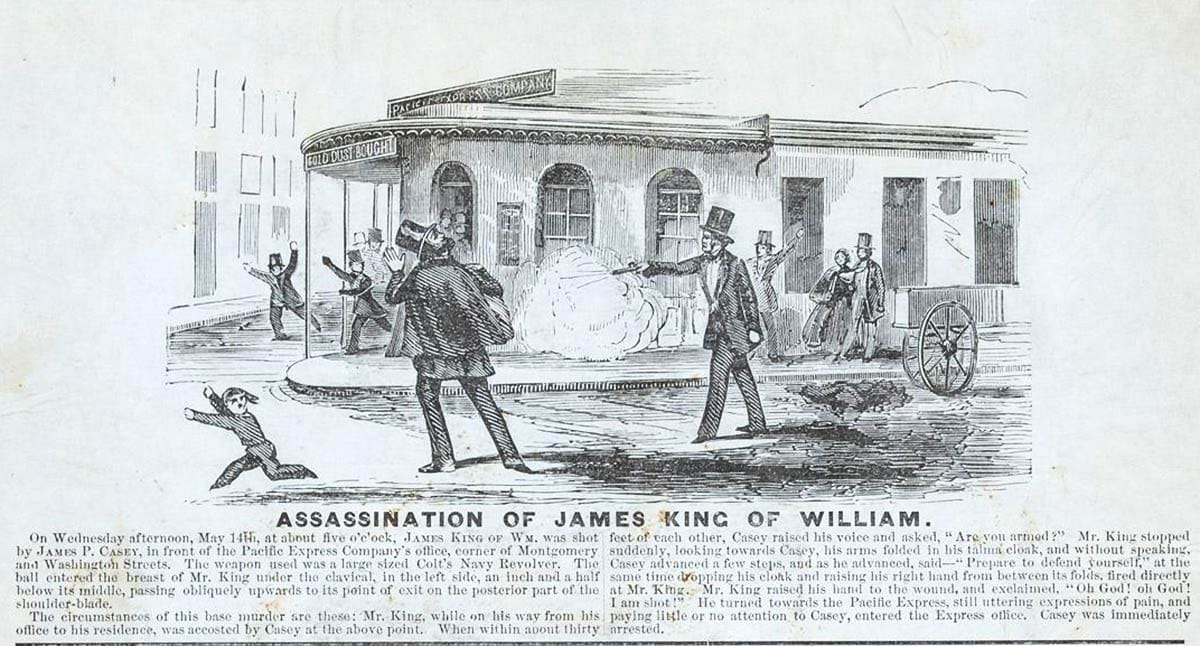

On May 14, 1856, a public shooting catalyzed a vigilante (and political) movement in San Francisco.

One hundred and sixty-nine years ago this week, on May 14, 1856, a prominent man shot another prominent man at the intersection of Montgomery and Washington Streets in San Francisco.

Supervisor James Casey had seen his past, which included a prison stint, raked up and published by Daily Evening Bulletin editor James King of William with a conclusion that Casey deserved “to have his neck stretched.”

This had followed a piece in Casey’s own paper, the Sunday Times, which accused King of smearing the U.S. Marshal in the Bulletin because King’s brother wanted the job.

Casey confronted King in the Bulletin offices, where he felt he was further insulted by King. Returning with a pistol, the supervisor shot the journalist in broad daylight at one of the city’s busiest intersections.

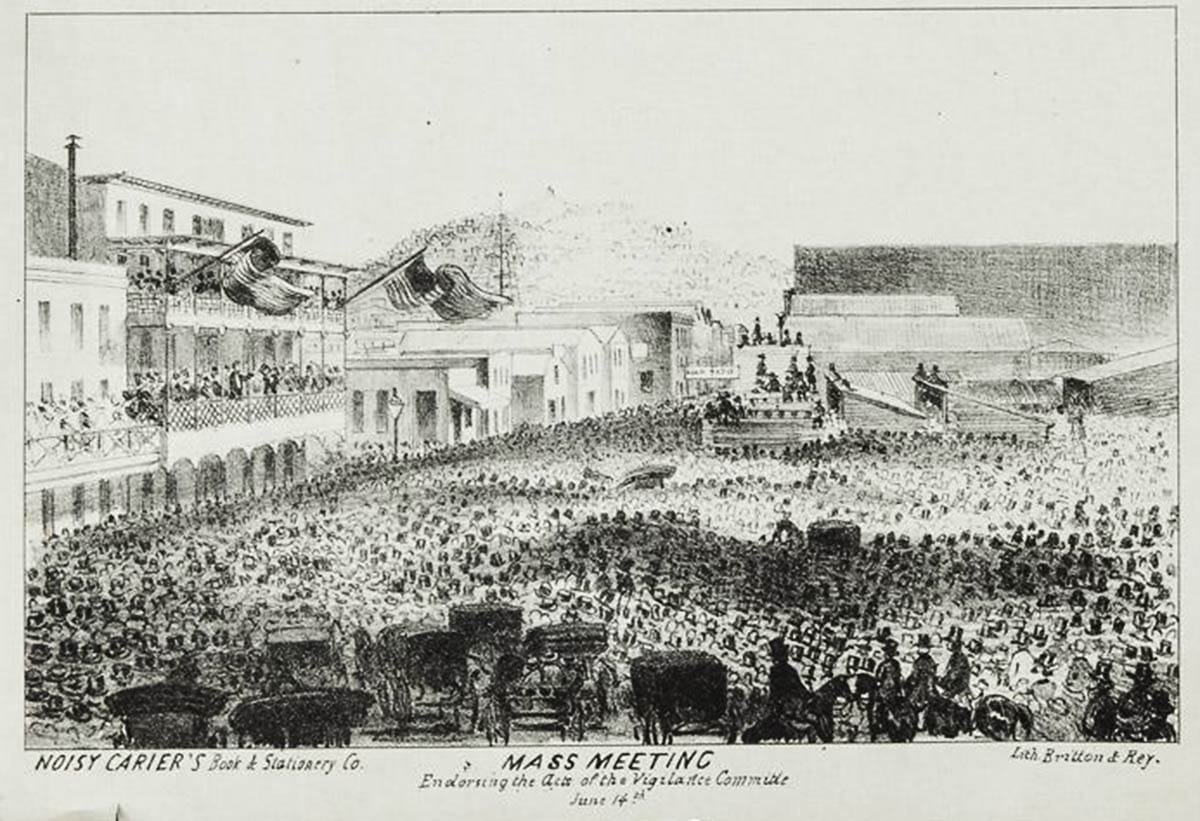

This act of violence sparked the formation of the young city’s second Vigilance Committee in which a massing of men, mostly leading merchants, decided to “unite themselves into an association for maintenance of the peace and good order of society.”

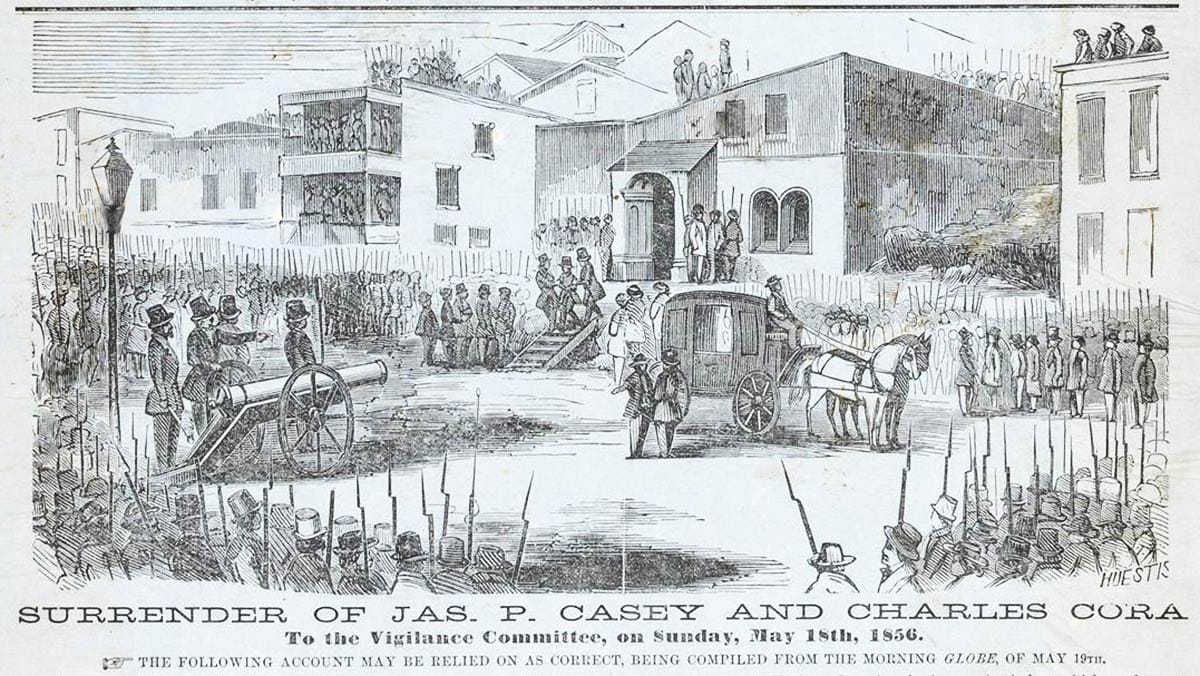

Despite a personal meeting and stern directive from the California governor not to interfere with the judicial process, the vigilantes formed in militia ranks and with a cannon pointed at the jail, politely removed Casey and another prisoner, Charles Cora, for a secret trial with one verdict possible.

Cora, a professional gambler, was removed with Casey because he was also linked with James King of William.

The previous November, Cora and a U.S. marshal, William H. Richardson, had a disagreement over an insult to Cora’s female companion. In an altercation at Clay and Leidesdorff streets (after both had been drinking at saloons), Cora shot Richardson with a derringer. He later claimed he believed Richardson, who was known to always carry two guns, was about to shoot him.

King as editor of the Daily Evening Bulletin spent the next few months using Richardson’s death to attack the city administration and the elected sheriff, David Scannell. King predicted Cora would be allowed to escape or that a jury would be bribed to let him off. The editor called for the sheriff and city jailer to be fired, banished, or even hanged if Cora somehow escaped justice.

When the first Cora trial ended in deadlock, leaving the gambler in jail awaiting a retrial, King started hinting at and encouraging the re-emergence of a Vigilance Committee to take the reins of government.

His own death at the hands of Casey fulfilled King’s wish.

The Great Public Emergency

Shocking as the King shooting was, did it represent the “great public emergency” that the Vigilance Committee claimed the city was under? Was it true that there was “no security for life and property?”

Was San Francisco a chaotic lawless frontier town requiring upstanding men to storm the city jail to institute justice?

That’s how the vigilantes would be popularly portrayed in San Francisco’s history for a long time: pure-hearted citizens said “no more” and came together in common cause to make San Francisco safe. It’s still generally portrayed that way on Wikipedia.

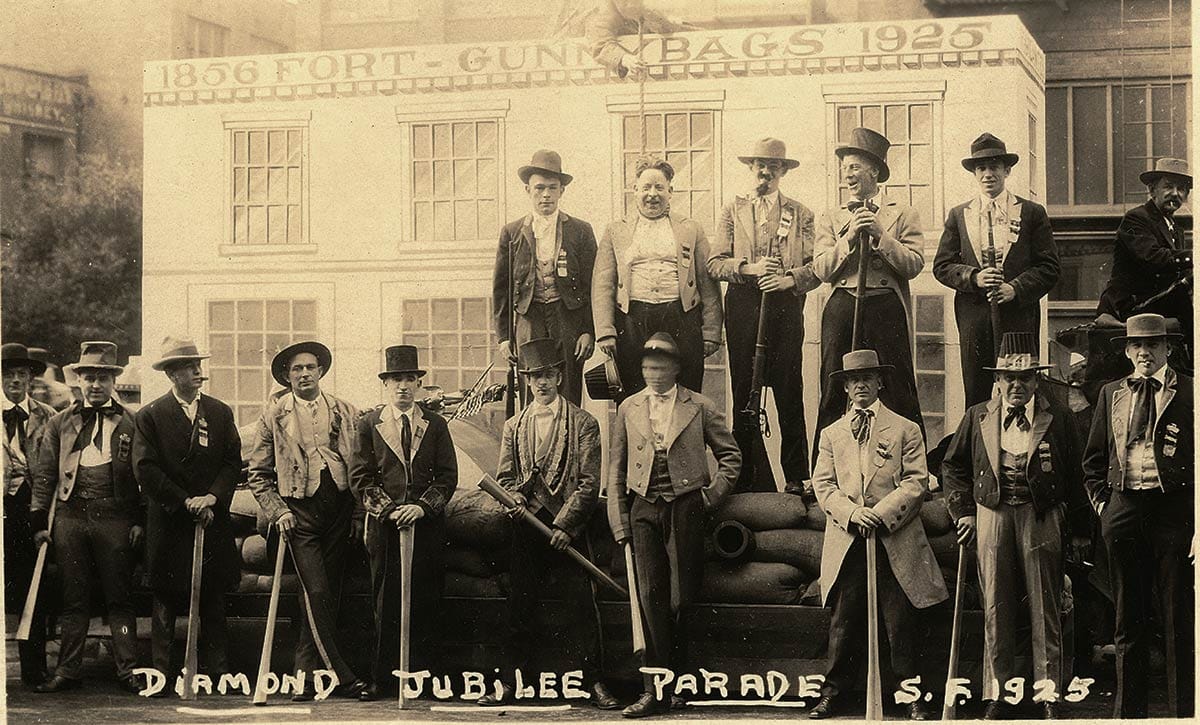

Below are men play-acting as Vigilance Committee members during the state’s diamond jubilee in 1925. On the parade float, second from left, one jolly gent got to wear a noose around his neck:

Historian Robert Senkewicz has noted that with the first Vigilance Committee in 1851 “It was not so much an actual increase in crime as an increase in the merchants’ fear of crime, on which they could blame their uncomfortable feelings of not doing well in the gold rush city.”

That the 1856 uprising was about local politics as much as shootings-in-the street is apparent in the language of the Vigilance Committee’s “constitution,” in which claims of ballot-box stuffing and voter fraud take up more space that any accounts of violence.

In the months before his death, James King of William had been railing against the Democratic party, which had won elective offices from more nativist Protestant factions. King specifically attacked members of the Democratic base: Roman Catholics and Irish immigrants.

King used the Charles Cora case as a cudgel against the perceived corruption of the electoral process and venality of the administration.

King was right about “electoral irregularities” and his suspected corruption in the local government. He would have been right about almost every city election and administration in the 19th century.

At the time of the 1855 contest most of the newspapers reported it one of the best conducted of the young city’s existence, but King and some powerful merchants did not like the results. When the editor was shot, one side of the political divide decided not to wait for the next election to make changes.

Justice

William Tecumseh Sherman would later achieve immortality as a general in the U.S. Civil War. In 1856, he was out of the Army managing a bank at Montgomery Street and Pacific Avenue. With the mayor and the governor on the roof of the International Hotel, he watched the transport of Casey and Cora from the city jail:

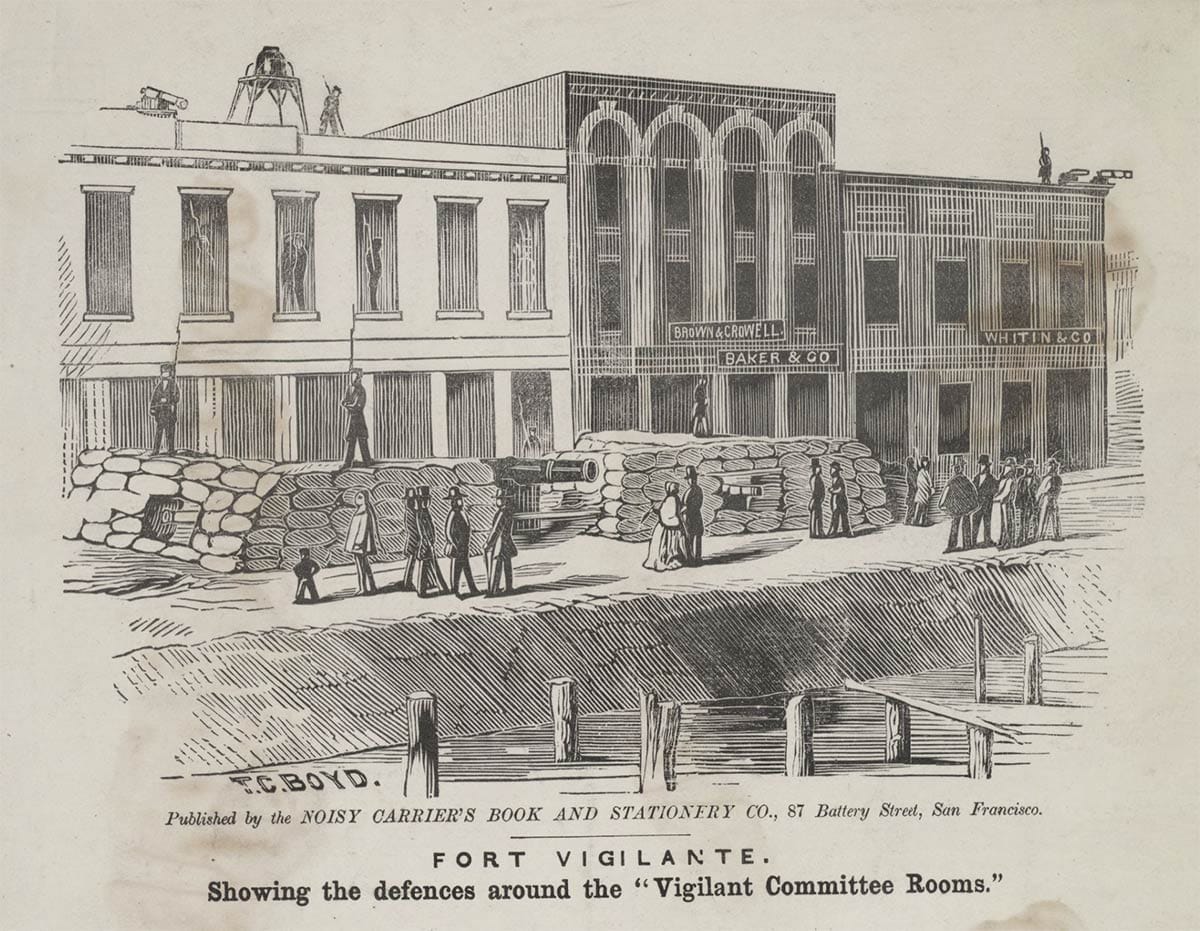

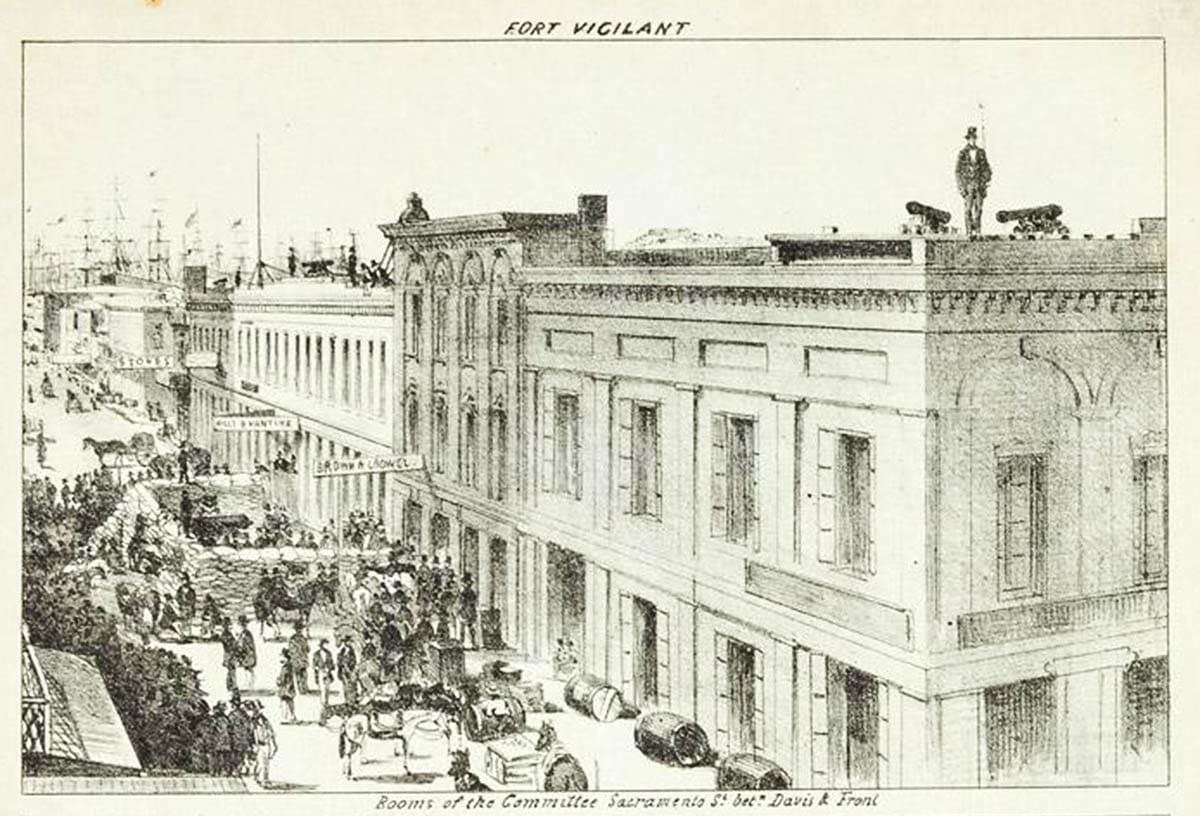

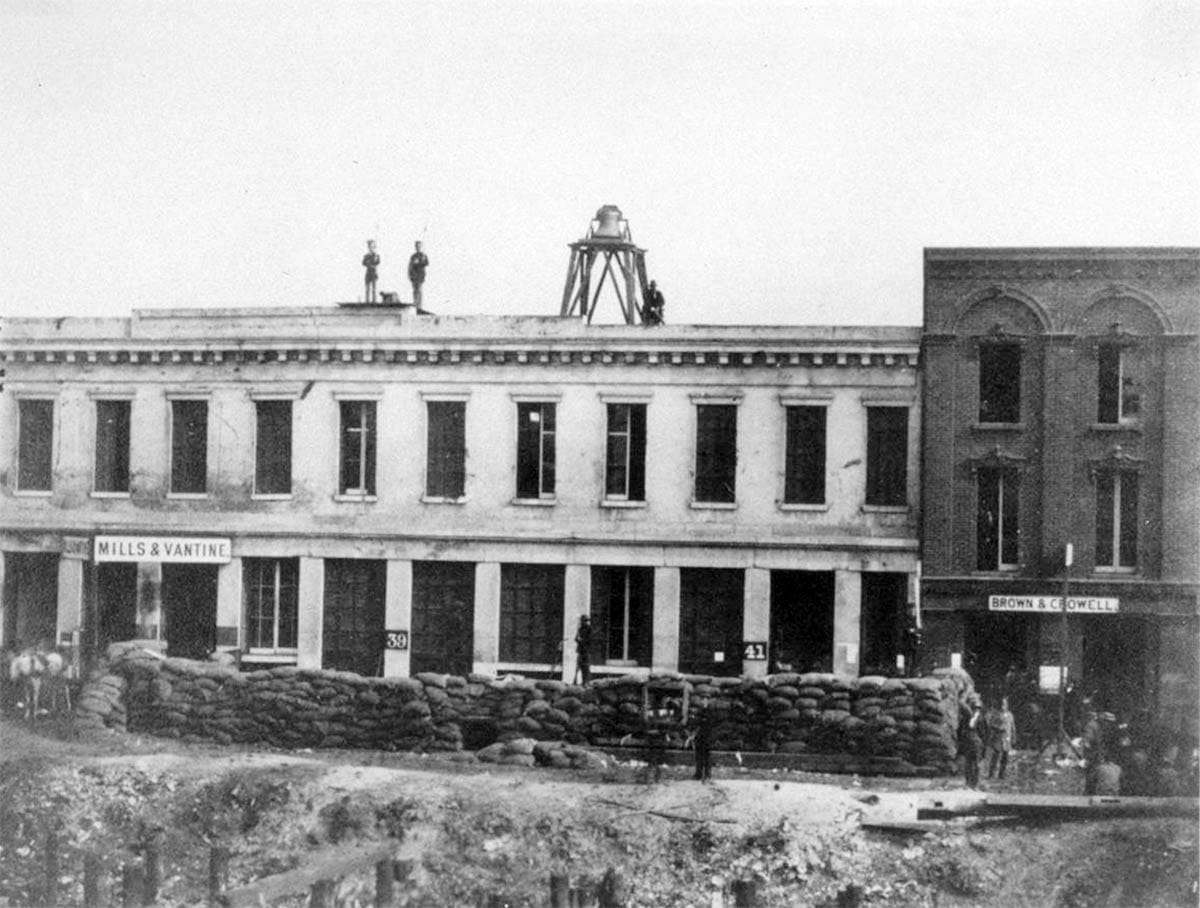

“[The] prisoners were placed in carriages, and escorted by the armed force down to the rooms of the Vigilance Committee, through the principal streets of the city. The day was exceedingly beautiful, and the whole proceeding was orderly in the extreme.”

He continued, “I was under the impression that Casey and Cora were hanged that same Sunday, but was probably in error; but in a very few days they were hanged by the neck–dead–suspended from beams projecting from the windows of the committee’s rooms, without other trial than could be given in secret, and by night.”

“We all thought the matter had ended there, and accordingly the Governor returned to Sacramento in disgust, and I went about my business. But it soon became manifest that the Vigilance Committee had no intention to surrender the power thus usurped.”

The vigilantes began settling personal and political scores. Almost all the city newspapers got vigilante fever, assisted by intimidation and loss of advertisers, to hail the extra-judicial actions of the growing committee.

Under a purported non-partisan banner (it was generally Protestants against Catholics, Yankee against Irish, and the Know Nothing party against Democrats), the Vigilance Committee banished individuals from the city, confiscated government arms, grabbed land title claims from political opponents, put the chief justice of California on trial, and ended up hanging two more men over the next three months.

As the movement wandered into broader political purges (and business began being disrupted), some prominent men began quietly dropping out. The governor issued an official proclamation demanding the vigilantes disband or San Francisco would be declared in insurrection. He appealed to the president for federal arms to put them down.

The Vigilance Committee finally ran out of steam and money. It formally and grandly disbanded with a public pageant on August 18, 1856. Its executive committee auctioned off memorabilia, including lumber from the scaffolding with which they hung two men.

The Democrats lost in the 1856 election when the vigilantes’ People’s Party— ostensibly non-partisan, but made up of former Know Nothings whose candidates were picked by a secret committee of 21 men—swept all the offices. It ruled San Francisco for the next decade.

You can draw your own modern parallels.

We have plenty today, locally and nationally. The crime or tragedy of the week is used for political ends through the media, which is very willing to assist. Attacking and discrediting the judicial system before verdict (or even trial) is now normal. With political and media support, miscreants and mobs can be made heroes of a story.

Although there were always opponents, and there have been recent reappraisals by historians, William Tecumseh Sherman summed up the legacy of of the 1856 vigilantes: “As they controlled the press, they wrote their own history.”

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

I had my annual physical and asked my doctor if he was OK with the amount and character of my weekly beverage intake. He approved and prescribed that I keep buying drinks for Friends of Woody. Why are people always complaining about Kaiser?

When are you free? Someone else already paid for your drink by contributing to the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund. Use it or lose it!

Sources

William T. Sherman, The Memoirs of General William T. Sherman (New York: D. Appleton & Co, 1889), 2nd Edition.

Robert M. Senkewicz, S. J., Vigilantes in Gold Rush San Francisco (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1985)

Nancy J. Taniguchi, Dirty Deeds: Land Violence, and the 1856 San Francisco Vigilance Committee (Norman, OK, University of Oklahoma Press, 2016)