Selling Westwood Park

Marketing bungalow life in 1910s San Francisco.

In 1911, Archibald S. Baldwin made one of the greatest land deals in the history of San Francisco. The notable real estate man pulled together investors to purchase 724 acres on the west side of Mount Davidson from the estate of the Adolph Sutro.

The late mayor and millionaire had planted thousands of trees on his hilly landscape and rented out lower-lying sections to tenant farmers. Now Baldwin and his partners envisioned tracts of artistic and expensive homes and, to serve all their new commuters, a streetcar tunnel piercing Twin Peaks.

Each corporate partner in the scheme would build their own “residence park,” a master-planned development of winding avenues, public landscape features, and deed-restricted houses to guarantee an “ideal home community.”

In an era before city planning departments, promoters of residence parks drew up and enforced their own land-use rules.

Deed restrictions defined construction costs, house designs, and property set-backs. Roadways curved and bent with the terrain and were lushly landscaped.

Residence parks excluded business or industrial use in the tracts and, in a virulently racist era, their housing covenants banned whole races of people: African Americans and “Asiatics” were prohibited from owning or occupying homes in the new enclaves.

In less than five years, Forest Hill, St. Francis Wood, and Ingleside Terraces had all become realities—designed, built, and sold house-by-house by different developers. The firm of Baldwin & Howell was the prime deal-maker in the overall effort.

In 1916, while all were still waiting for the completion of the Twin Peaks Tunnel and the promised streetcar service, Baldwin & Howell moved to make its own ideal home community in the forest along the north side of Ocean Avenue.

Residence parks were almost by definition designed and marketed to upper-class buyers—doctors, lawyers, capitalists, industrialists, and corporate heads—but with the new Westwood Park, Baldwin decided on an experiment.

Instead of a development for doctors and lawyers, he would make a residence park for their accountants and clerks.

Bungalow Fever

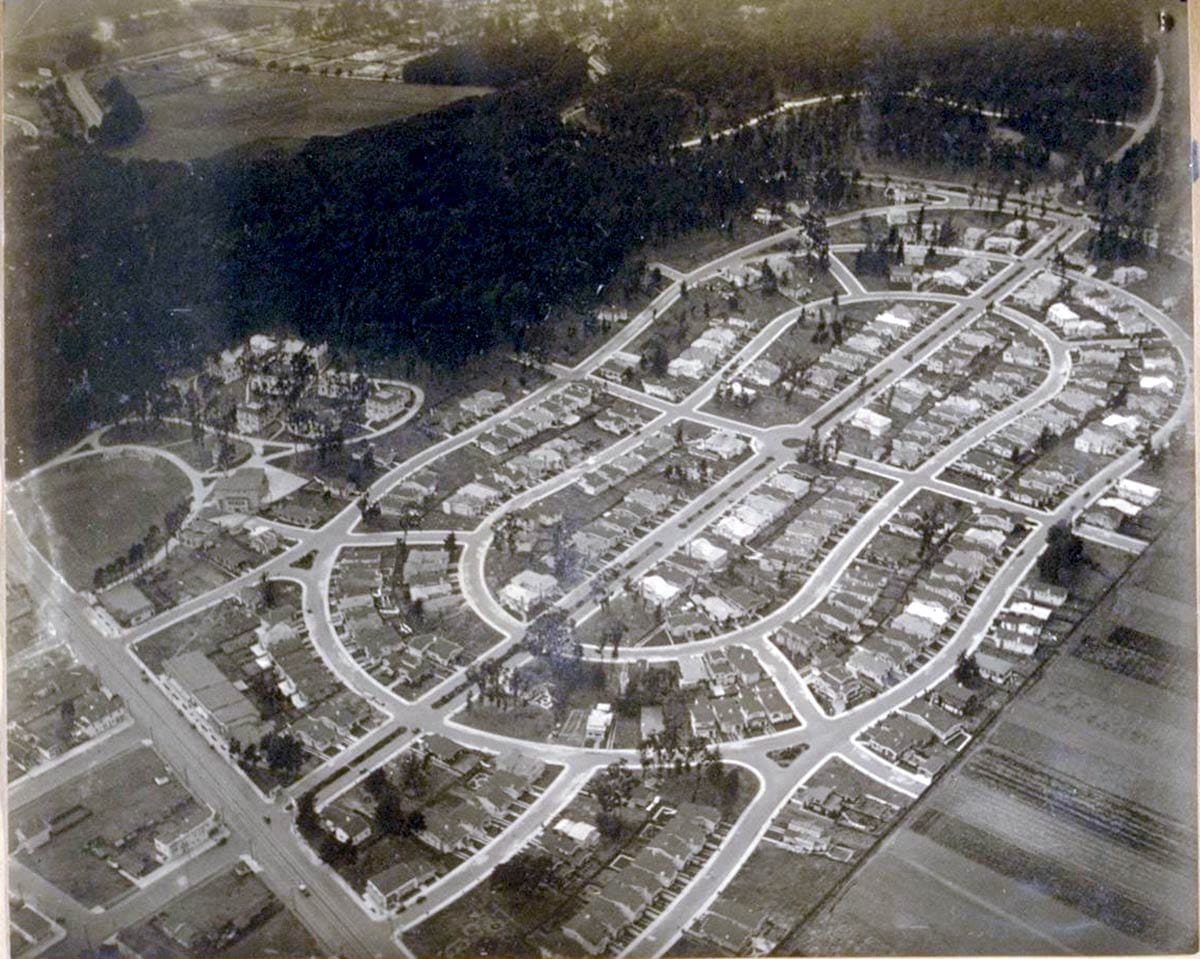

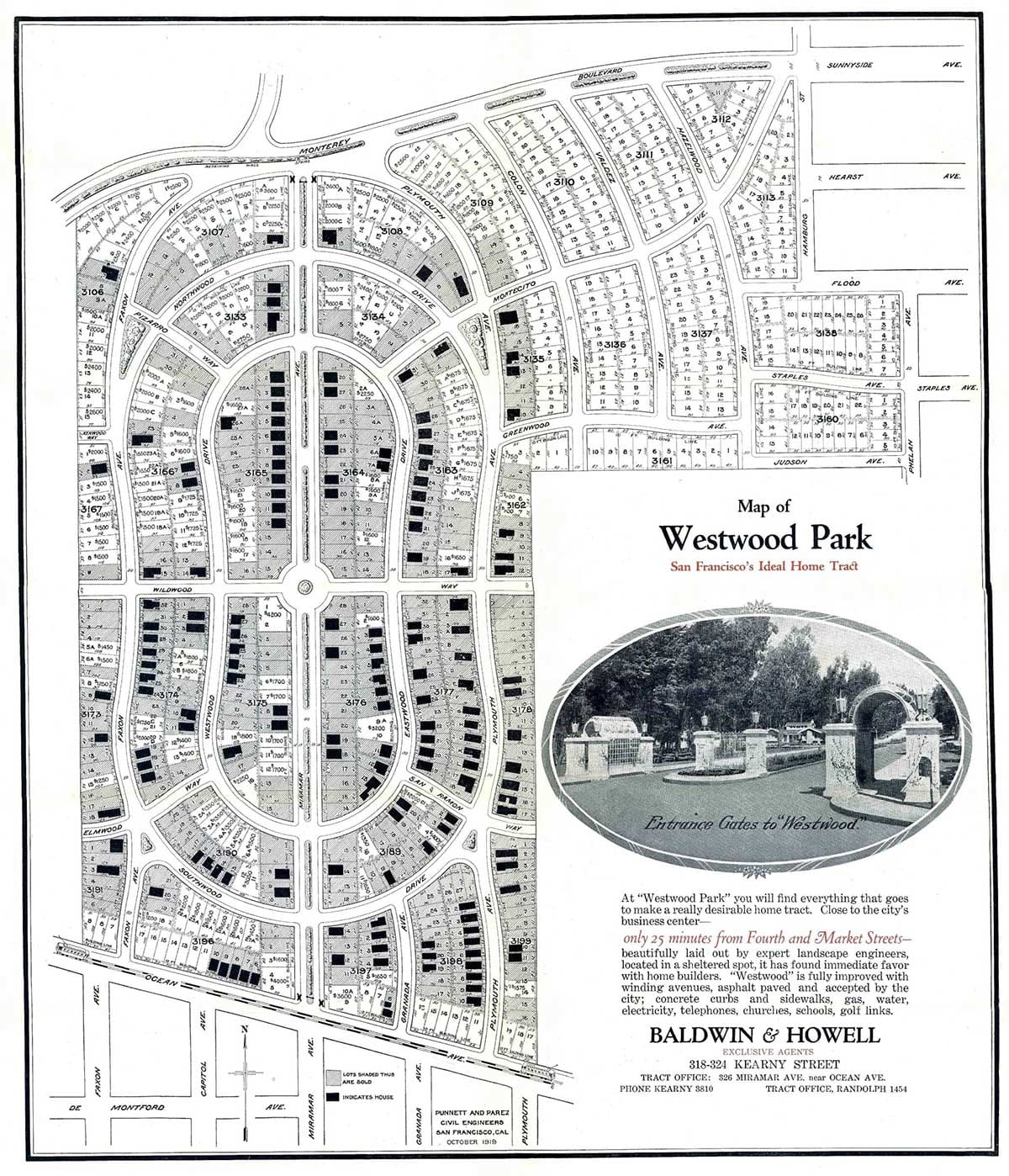

Westwood Park was mapped out in two concentric ovals over 93 sloping forested acres between Ocean Avenue, Monterey Boulevard, Faxon and Plymouth Avenues (plus an “annex” section on its northeast corner).

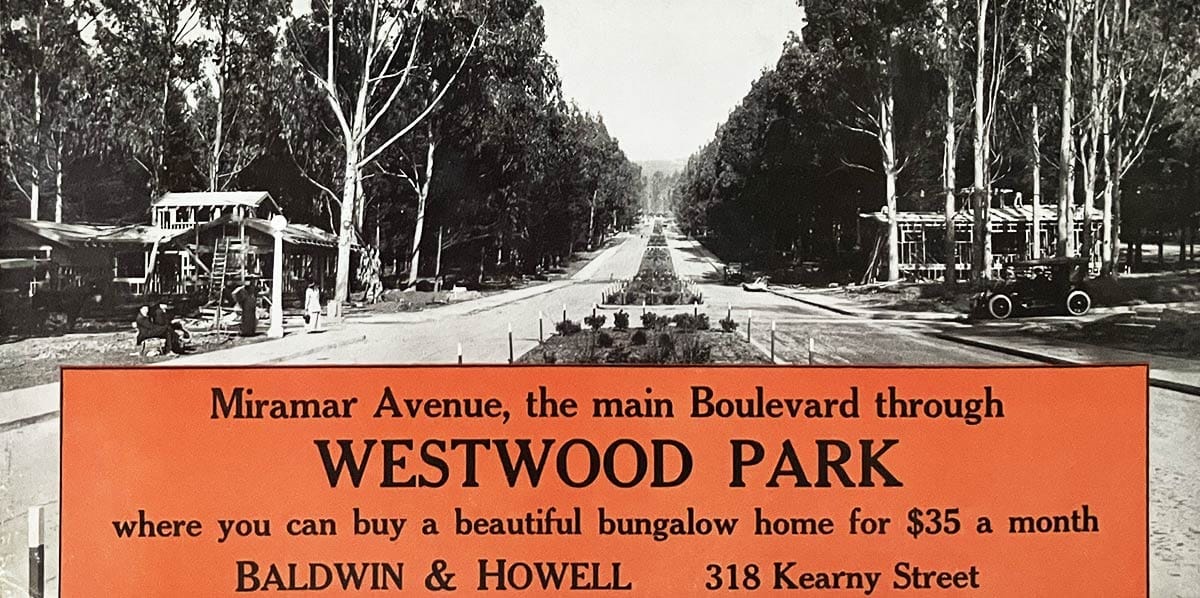

Miramar Avenue, the spine of the ovals, was the showplace boulevard.

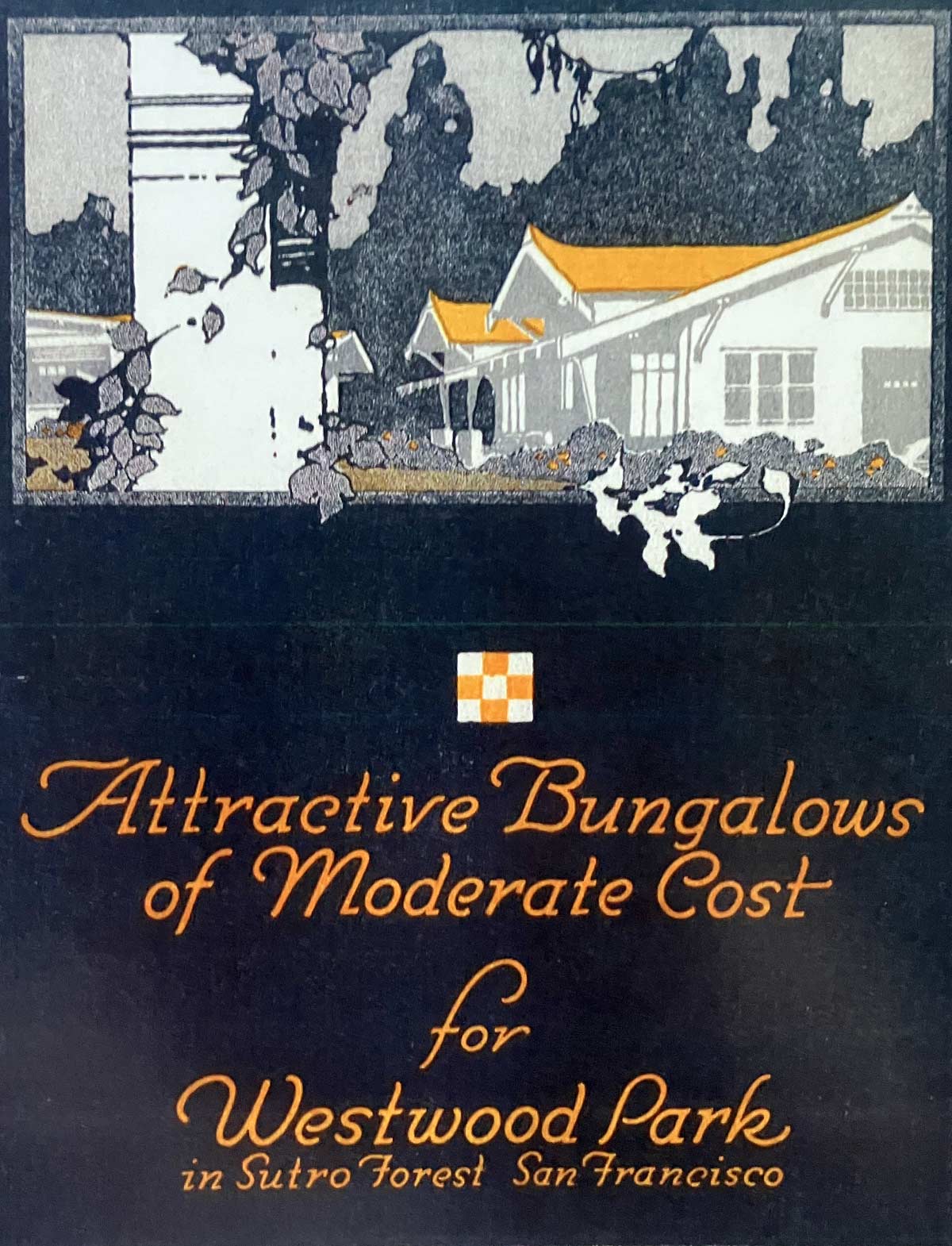

Baldwin & Howell included both landscape amenities and deed restrictions similar to St. Francis Wood and Forest Hill, but instead of grand houses with maid’s quarters and solariums, Westwood Park was meant to be a “moderate means” community of bungalows.

California had bungalow fever in the 1910s. Subdivisions of the humble and popular Arts and Crafts homes spread through Long Beach, Riverside, Pasadena, and other Southern California communities.

Characterized by single-story floor plans, wide front porches, and deep-eave roofs, bungalows were also known for rough-hewn facade elements, natural colorings, and brick or stone foundation facades.

They were also inexpensive to construct. Many were built from mail-order kits.

Baldwin’s scheme: build lots of relatively cheap but attractive bungalows on his woody hillside tract and suck in buyers attracted to the trappings and restrictions of hoity-toity residence park life.

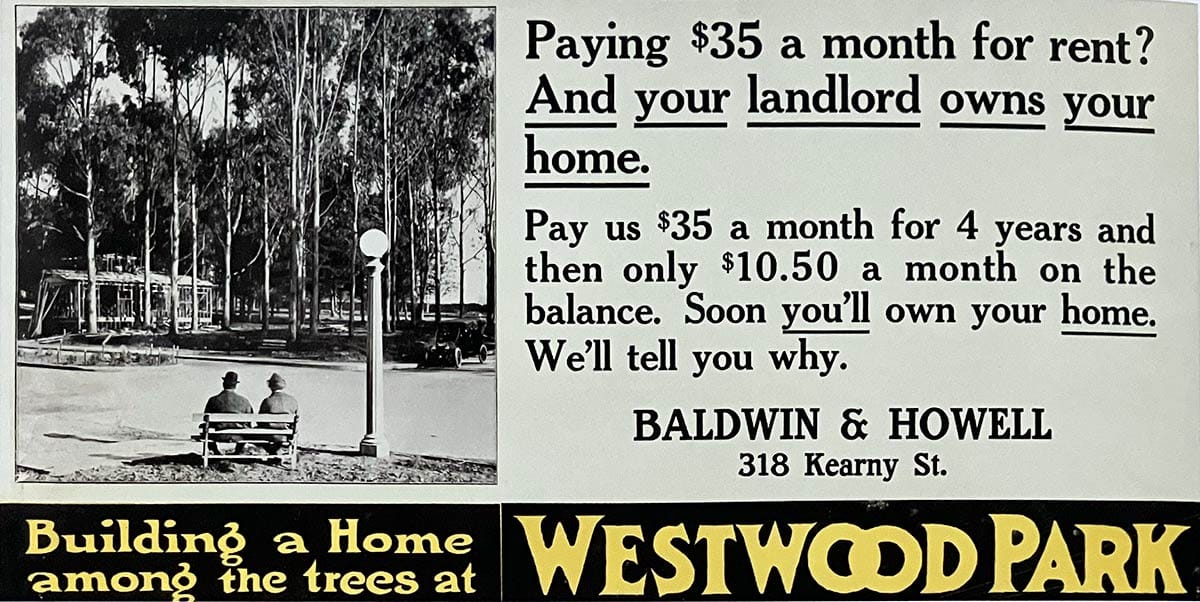

After chopping down a lot of eucalyptus trees, Baldwin & Howell formally opened Westwood Park for sale on October 15, 1916. Lots were priced from $1,050 to $2,250 (about $30,000 to $66,000 in 2025 dollars) and were five to 15 feet wider than San Francisco's standard 25-foot-wide lot.

Sales agents gave prospective buyers a book with thirty-four bungalow plans to choose from, although in some cases people purchased lots and designed their own houses.

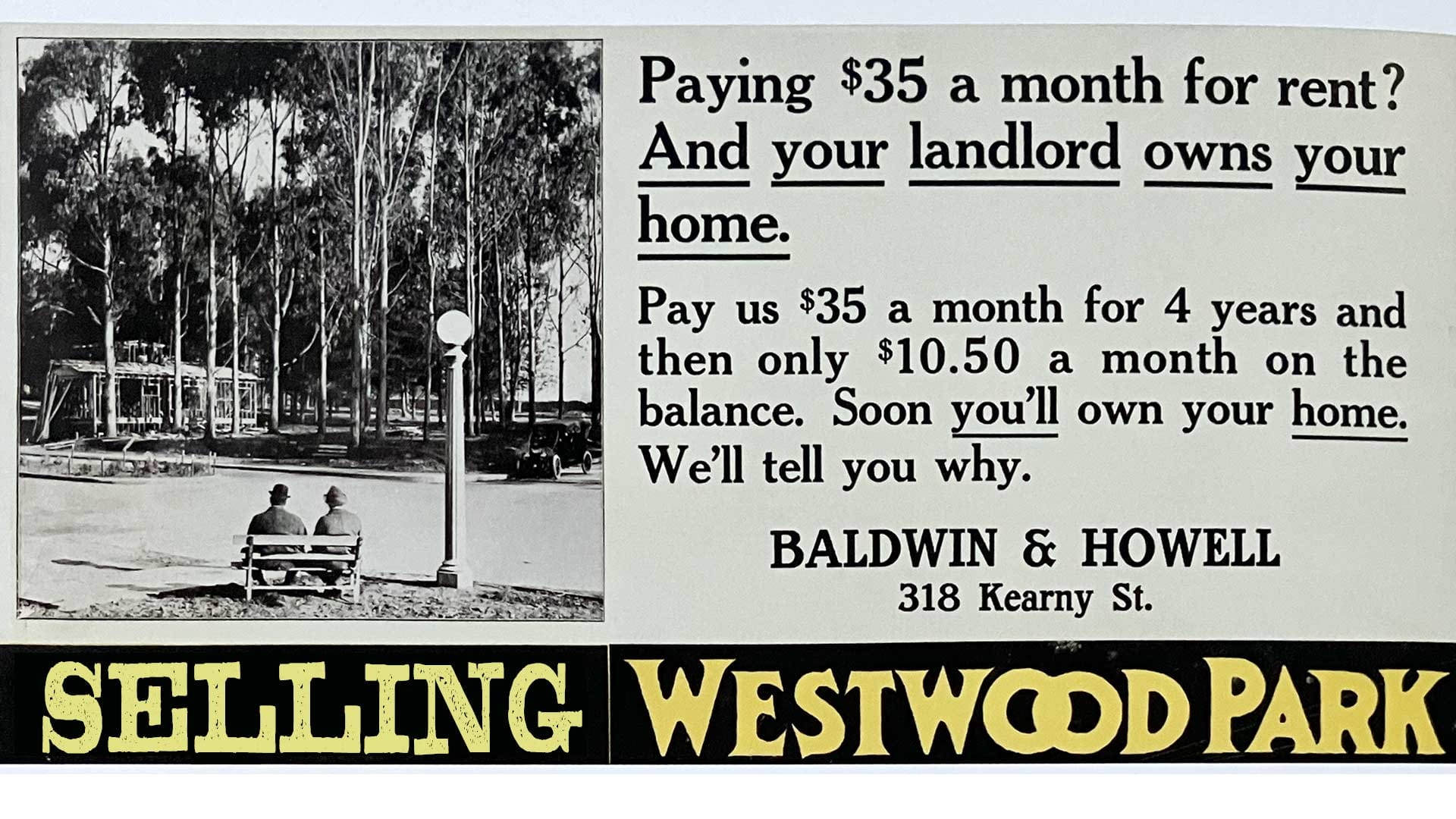

A Westwood Park bungalow could be had for a down payment of $400 with ten-year mortgage payments of $35 a month.

So, while a property in neighboring St. Francis Wood or Ingleside Terraces might cost $12,000 to $20,000 total, a pleasant Westwood Park house in a similar setting went for less than $6,000 ($177,000 in 2025 dollars).

Not a bad deal. Still, Baldwin took no chances with his marketing campaigns.

Artistic Surroundings for Moderate Means

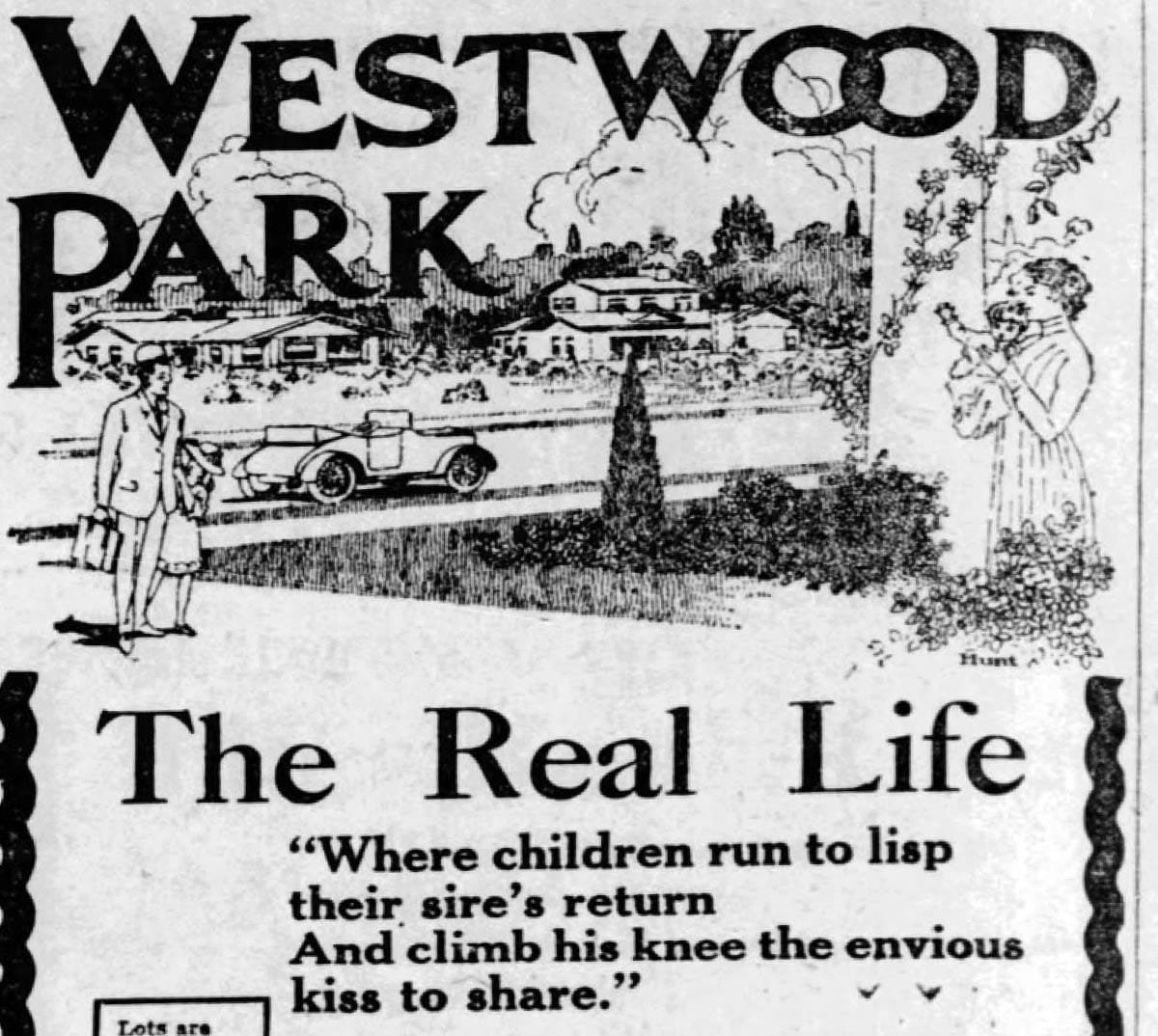

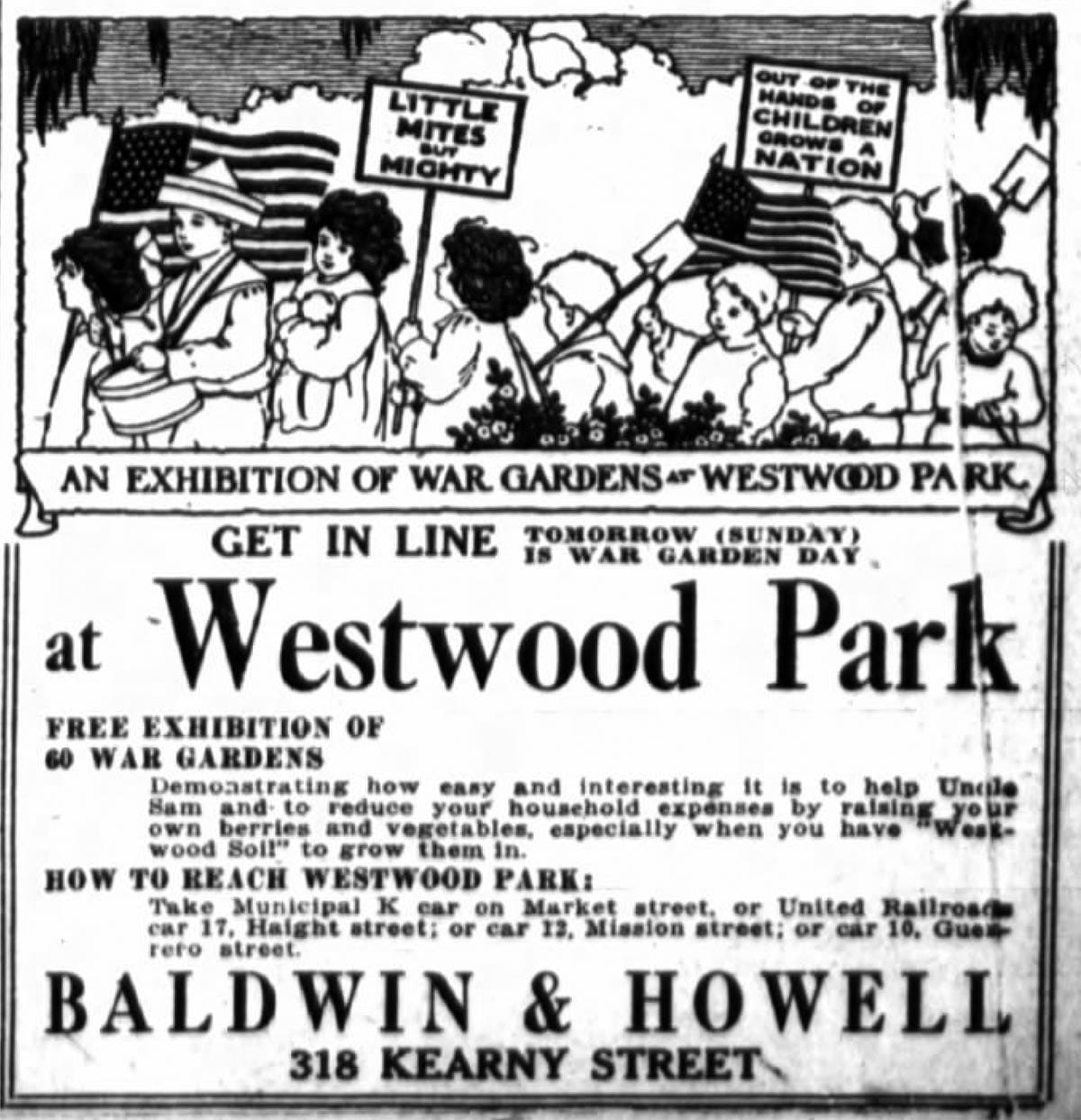

In their newspaper ads, Baldwin & Howell trumpeted Westwood Park as no less than the “tenth wonder of the world.” Lavish testimonials were published weekly from planners, city officials, and happy homemakers. Lots of drawings of children in idyllic garden homes:

Any possible qualms about buying were countered in one of Baldwin's advertisements or newspaper editorials.

Foggy locale? Westwood Park was in “the most sheltered portion of Sutro Forest,” and ample sunshine was always mentioned (or at least imagined).

Too far from work? When the tunnel was finished it would be “22 minutes from Westwood Park to 3rd and Market.”

An uncertain investment? “Upon completion of the Tunnel we confidently believe that lots in Westwood Park will be selling at from 50 per cent to 100 percent more.”

Buying in Westwood Park was apparently even curative because, as the company proclaimed “young married people find that the sunshine and fresh air take the place of medicines for their children...”

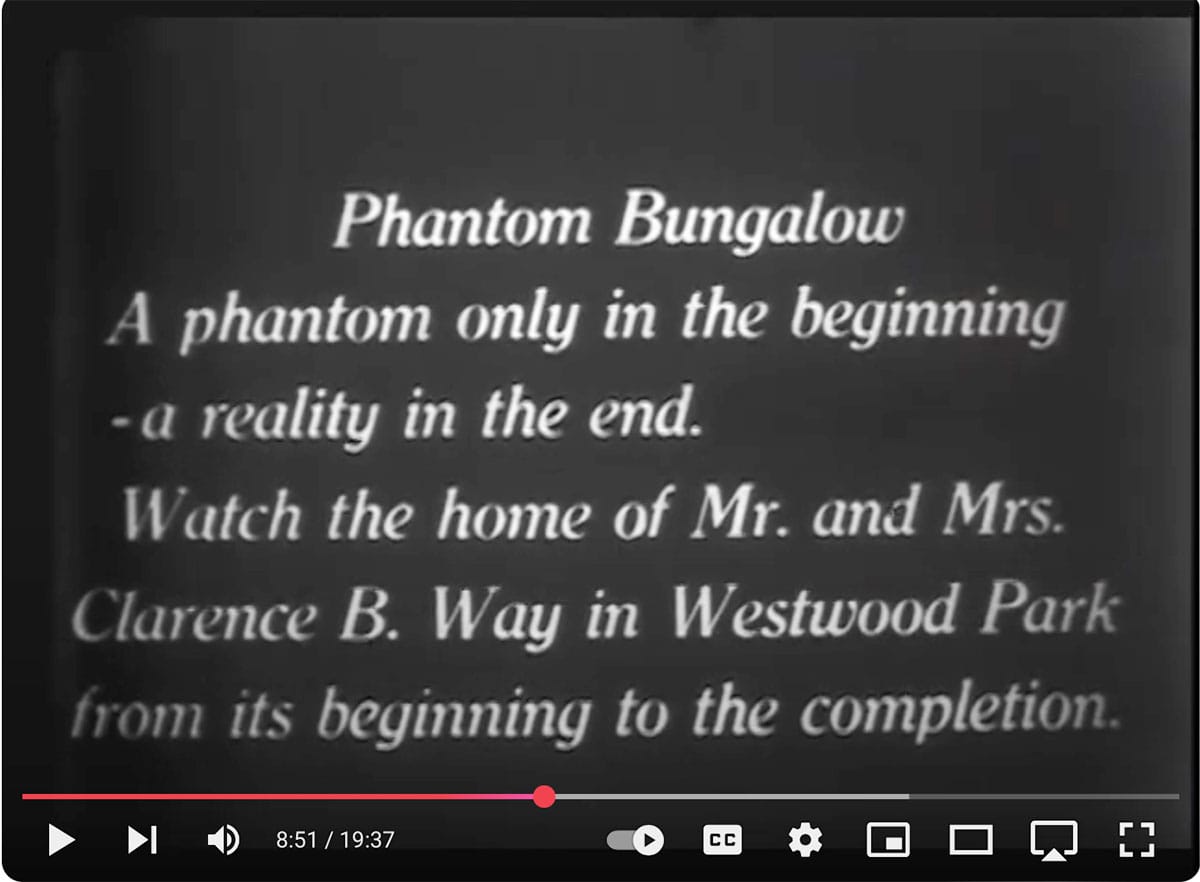

Baldwin & Howell’s advertising budget included commissioning a short film on the tract's virtues and progress, featuring a time-lapse sequence of a bungalow’s construction from framing to ivy-covered completion.

Although bungalows were inexpensive to build and could be simple in design, Baldwin & Howell used accomplished architects such as Charles F. Strothoff and Ida F. McCain to create imaginative versions of the form: “Colonial bungalows” and “English bungalows.”

When a wind storm hit the Bay Area, an ad promoted Westwood Park’s “imposing bungalows.” Whatever works, I guess.

Of course, the company featured the architects in ads.

When the Tunnel is Complete

The promise of Muni’s Twin Peaks streetcar tunnel and a quick commute to work was a key buying proposition for West of Twin Peaks residence parks, especially for Westwood Park.

Baldwin and Howell’s buyers might own an automobile (almost all Westwood Park homes incorporated a garage on their lot), but clerks were more likely to rely on streetcar service than their bosses in St. Francis Wood.

Illustrating its importance, Baldwin & Howell featured the tunnel in a lot of its advertising. On giveaway promotional coins one side featured an embossed Westwood Park bungalow while the obverse showed a streetcar exiting the tunnel with a catchy motto: “When the tunnel is complete, to Westwood Park we will retreat.”

Just as the tunnel was nearing completion, the United States entered World War I. Advertising shifted smoothly, if shamelessly, to keep sales going.

Buyers were encouraged to “join an army of home seekers” viewing Westwood Park. The U.S. Vice-President was shown holding a baby with a quote that he would be willing to die for his home, but “shall never shoulder a musket in defense of a boarding house.”

One post-war ad in The Home Designer magazine was practically a political manifesto on protecting Democracy:

“We believe that the American home is the bulwark of the Nation and its mightiest safeguard against the revolutionary tendencies that fain would undermine its greatness. We see in the home the gateway to independence, the molder of sturdy character and the source of true patriotism.”

Buy a bungalow in Westwood Park or join the Communist Party. It’s your choice.

By 1920, just four years after its ground-breaking, despite materials restrictions of World War I and the Twin Peaks Tunnel’s delayed opening, Westwood Park had close to 450 residents.

The U.S. Census that year reveals that Baldwin’s achieved his vision of a residence park for “the family of average means” (of course meaning the white family of average means).

The most common professions listed for employed Westwood Park residents were middle management, sales, and accounting.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Contributed to by readers like you, the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund is safely invested in no-yield investment vehicles akin to my old 1963 Buick Electra. Dividends are paid in cups, mugs, and pints to both investors and random people who want to talk to me in person.

I am starting to get back in the groove and have a number of beer and/or coffee dates on the calendar!

In early July, Nancy and I will be taking a trip up to Ashland, Oregon (Shakespeare) and then I will head to see my uncle and aunt’s art show in British Columbia, but we can schedule ahead a bit, right?

Let’s pick a date to meet up.

Sources

Great thanks to friend Kathleen Beitiks, who wrote the book: Westwood Park: Building a Bungalow Neighborhood in San Francisco. You can buy it from Western Neighborhoods Project, but you might have to email Nicole to figure out how. 😄

They also have Richard Brandi’s book Garden Neighborhoods of San Francisco: The Development of Residence Parks, 1905-1924, another great resource.