Still Lucky

In 1898, "Lucky" Baldwin lost a big bet with one of San Francisco's most notable fires.

Elias Jackson Baldwin’s fortune-hunting in San Francisco began with a hotel. A month after buying the Pacific Temperance Hotel in 1853, Baldwin flipped it for twice what he paid. Then he bought another hotel, The Clinton, which proved a spectacular failure.

Those would not be the last boom-bust experiences “Lucky” Baldwin lived through. With a sine wave career of successes and failures, triumphs and scandals, the eternal schemer might have been better nicknamed “Perseverance Baldwin.”

Baldwin commercial ventures and entanglements included livery and lumber businesses, real estate speculation, viticulture, stock market jobbing, racehorse raising and racetrack building, banking, vaudeville management, as well as four (maybe five) marriages and four extramarital relationships. Each of the latter were front-page-scandals and included paternity suits and being shot at by two different women, once in a courtroom.

This month marks the anniversary of likely the lowest of Lucky Baldwin’s lows as well as San Francisco’s most notable fire between the Gold Rush and the 1906 earthquake.

Palace before the Palace

The Palace Hotel on the corner of Market and New Montgomery streets is the best known of San Francisco’s Gilded Age hotels, a product of the wealth of the Nevada’s early 1870s Comstock Lode and a favored stopping place of famous opera singers and visiting presidents both before and after the hotel was rebuilt following the 1906 earthquake and fire.

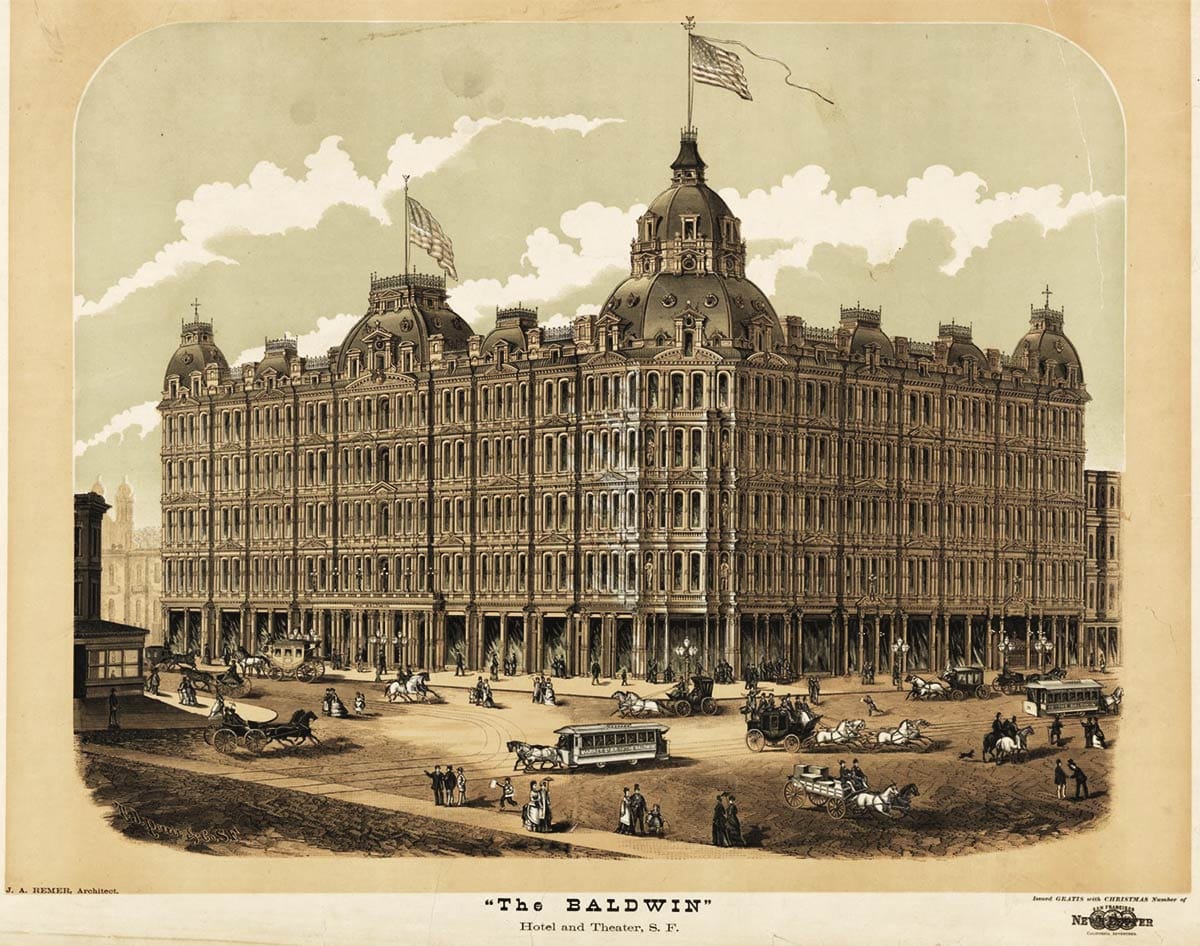

But it wasn’t the city’s first luxury hotel to be constructed from silver-mine wealth. In 1873, Lucky Baldwin was riding perhaps the highest of his highs with a vast fortune made from investments in the Ophir, Crown Point, and other Comstock mines. On the corner of Powell and Market streets—then practically considered the outskirts of town—he began construction on the finest hotel west of the Mississippi River.

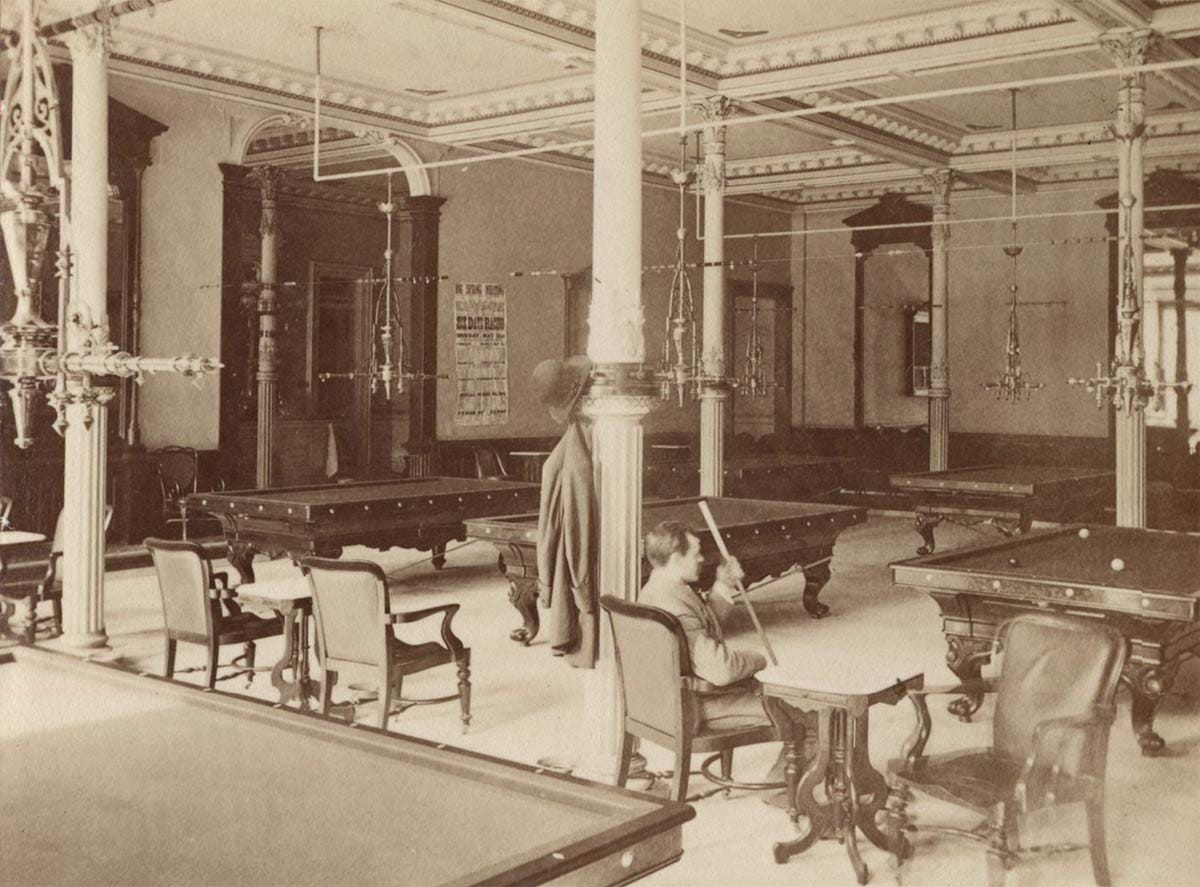

Baldwin hired architect John A. Remer to design his pile of towers and cupolas in French Renaissance style. The inside halls, dining rooms, and bars sported the expected chandeliers, red-velvet couches, mahogany finishes, and classical columns.

A Tiffany-constructed clock in the lobby cost Baldwin a reported $25,000. Mark Twain supposedly said “It not only tells the hours and minutes and seconds but the turn of the tides, the phases of the moon, and the price of eggs and who’s got your umbrella.”

Less expected features were paintings of Lucky Baldwin’s prized racehorses and scenes from his own life (including one of him escaping Indians while crossing the plains to California in the early 1850s). The building also housed a theater. While named the Academy of Music, it hosted everything from Shakespeare to modern comedies over two decades.

The whole venture cost over $3 million to construct (roughly $74 million in 2025 dollars) and Baldwin barely scraped through two financial crises in the four years it took to complete. And despite the horse paintings and $25,000 clock the uptown hostelry’s thunder was mostly stolen immediately by the construction of the competing Palace Hotel.

The Baldwin Hotel never made its namesake a fortune. Mr. Lucky ended up leasing it out to unload its operating headaches and expenses. But it was a significant asset to borrow against as the city grew west, Union Square transitioned into the city’s premier retail district, the mansions of the ultra-rich went up on Nob Hill, and the Powell street cable car line—still running today—was constructed outside the front door.

Baldwin used mortgages on the hotel to gobble up land in Southern California, buy and raise racehorses, and pay off many lawsuits and divorce settlements. In 1898, the Hibernia Savings and Loan bank held a $900,000 lien on the Baldwin hotel and theater property.

The Long-Predicted Tragedy

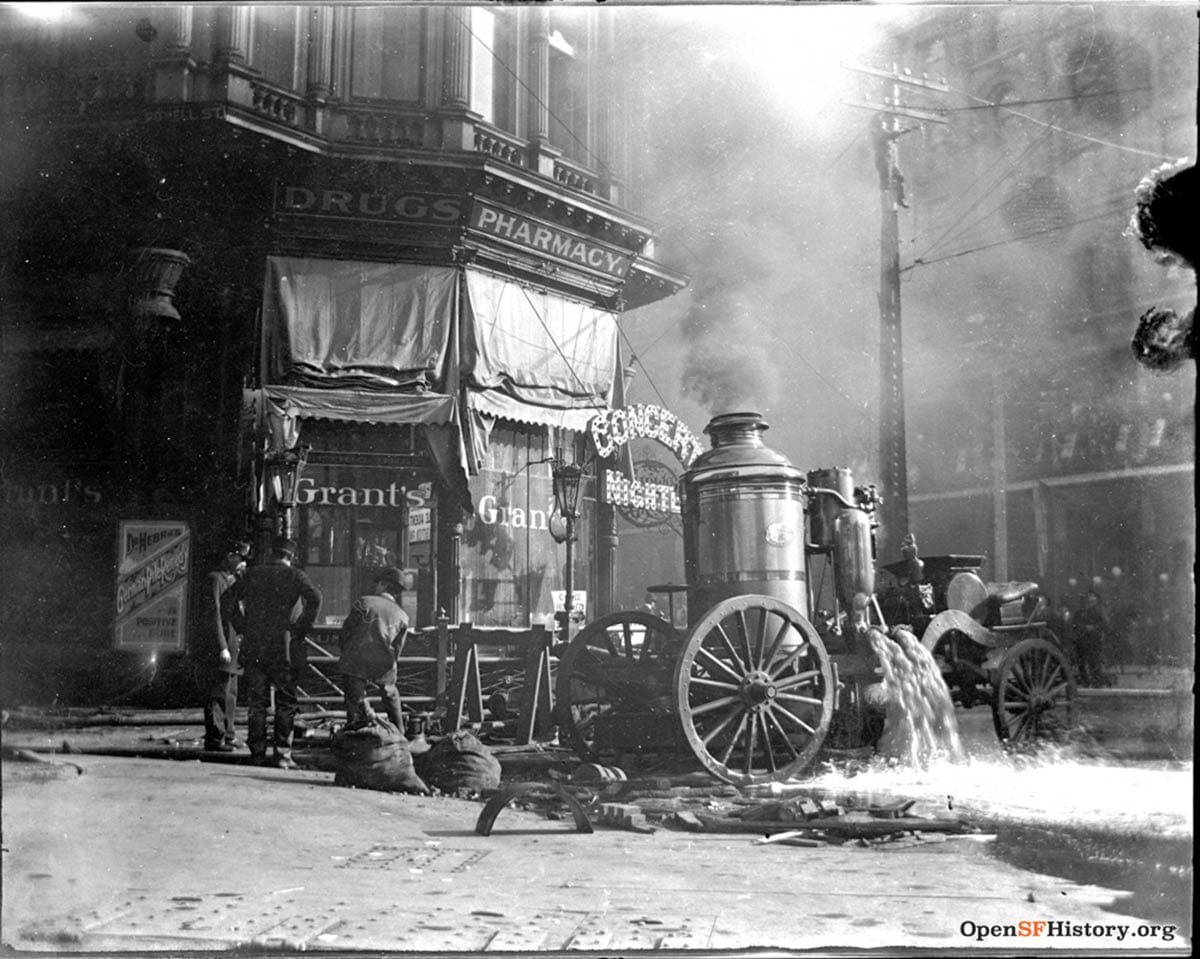

On November 23, 1898, a little after three in the morning, a fire broke out in the Baldwin Hotel, climbed a shaft, and burst out on its 5th floor. The walls were quickly sheets of flame and the blaze ran up and down the hotel’s air and elevator shafts. Smoke filled the upper floors of the hotel, the electric power went out, and employees took turns frantically running door to door and ringing the hotel’s alarm bell to rouse the more than 200 guests and servants.

By the time the fire department arrived the roof was ablaze and most stairways were impassable infernos. Escapees watched in horror as stranded guests crawled out on ledges near the roof and others yelled from upper windows along Market street. There were some metal fire escapes, but they were widely spaced-out on the building’s facades. Fire department ladders were too short to reach the desperate, trapped people on the fifth floor and the roof.

While the fire “raced like a hunted deer.” Men and women clung to rain gutters and cornices, shuffling to reach ladders and tossed ropes. The crowd on the street yelled advice and encouragement, gasped and cried.

On the 5th floor, Miss Kate Richardson and permanent guest John L. White were able to find a rope to help three stranded women down to escape. After lowering Richardson to safety, White then tied the rope around himself to make his own descent. “He was a heavy man,” reported the Call, “and the rope was small. It stretched, snapped, and the man plunged down to the stone sidewalk.

“He was dead before they raised him from the pavement.”

Three thieves who seemed to know what they were doing sneaked into the hotel during the fire and snatched a heavy trunk of diamonds and jewelry owned by an agent of an East Coast firm. A police officer saw them lugging it up O’Farrell street and when the men stopped to try and jimmy it open, the office took a few pistol shots at them.

He winged one as the trio scattered in different directions.

Four people died in the fire, another two in the immediate aftermath from heart attack and alcohol poisoning. It could have been worse. That such a tragedy could happen was not a surprise. The Examiner’s lede was “The long-predicted tragedy of the Baldwin hotel and theatre has come at last” and Call’s story on the “fire-trap” began with a one-sentence paragraph: “It has come at last!”

Lucky Baldwin was a survivor. Employees broke down his door and dragged him out of the inferno. A $7,000 gold racing harness had reportedly been left behind in his room, but the boss couldn’t get anyone to take the risk of retrieving it.

He had a bigger problem anyway. The building was totally uninsured.

Lucky and Unlucky

The day after the fire the battle-scarred Baldwin told the Chronicle that it was “one of the events that one must expect in the course of a lifetime.” He was able to sell his property to another rich Comstock man, James Flood. Today we have the Flood Building on the site where the Baldwin Hotel once stood. In the end, with his Southern California land holdings and other ventures Lucky Baldwin still died a multi-millionaire.

San Francisco fire chief Dennis Sullivan saw the city itself as lucky. The water mains ran dry in surrounding neighborhoods during the fight against the Baldwin Hotel blaze. Sullivan noted that if another fire had broken out in the district at the same time “life and property would have been at the mercy of the flames.”

Such an occurrence came less than eight years later. On April 18, 1906 a major earthquake sparked fires in multiple places. Most of the city burned.

After the earthquake, an auxiliary water system was installed for the core of the city. The western and southern sections, some 15 San Francisco neighborhoods where hundreds of thousands of people now live, are not yet covered.

We who live on the west side wonder how long our luck will last.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

A reminder that you are welcome to celebrate my 60th birthday with me on Saturday, November 29, from 5-8-ish at The Plough and The Stars at 116 Clement Street in the beautiful Richmond District of San Francisco.

No worries if you can not make it. We can use some of the Woody Beer and Coffee Fund another time. Just let me know when works for you!

Sources

“The Baldwin Hotel Entirely Gutted By Fire,” San Francisco Call, November 23, 1898, pg. 1.

“Four Lives Forfeited in the Baldwin Hotel Fire,” San Francisco Examiner, November 24, 1898, pg. 1.

“A Relic of the Old Bonanza Days,” San Francisco Call, November 24, 1898, pg. 3.

“Some Side-Lights on a Big Fire,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 27, 1898, pg. 7.

Carl B. Glasscock, Lucky Baldwin: The Story of an Unconventional Success (Reno, NV: Silver Syndicate Press, 1993)