The Last to Know

San Francisco stories end with the last storyteller.

Nettie Meyers was a year old when it happened.

On the afternoon of Friday, September 19, 1890, her father’s crew was raising iron girders to upper floors of San Francisco’s under-construction city hall.

A 48-year-old native of Bornholm, Denmark, Charles Meyers had been a ship-rigger and then, over many patient years, built up a partnership in a small Howard Street rigging firm. He was probably happy to have secured the subcontracting job.

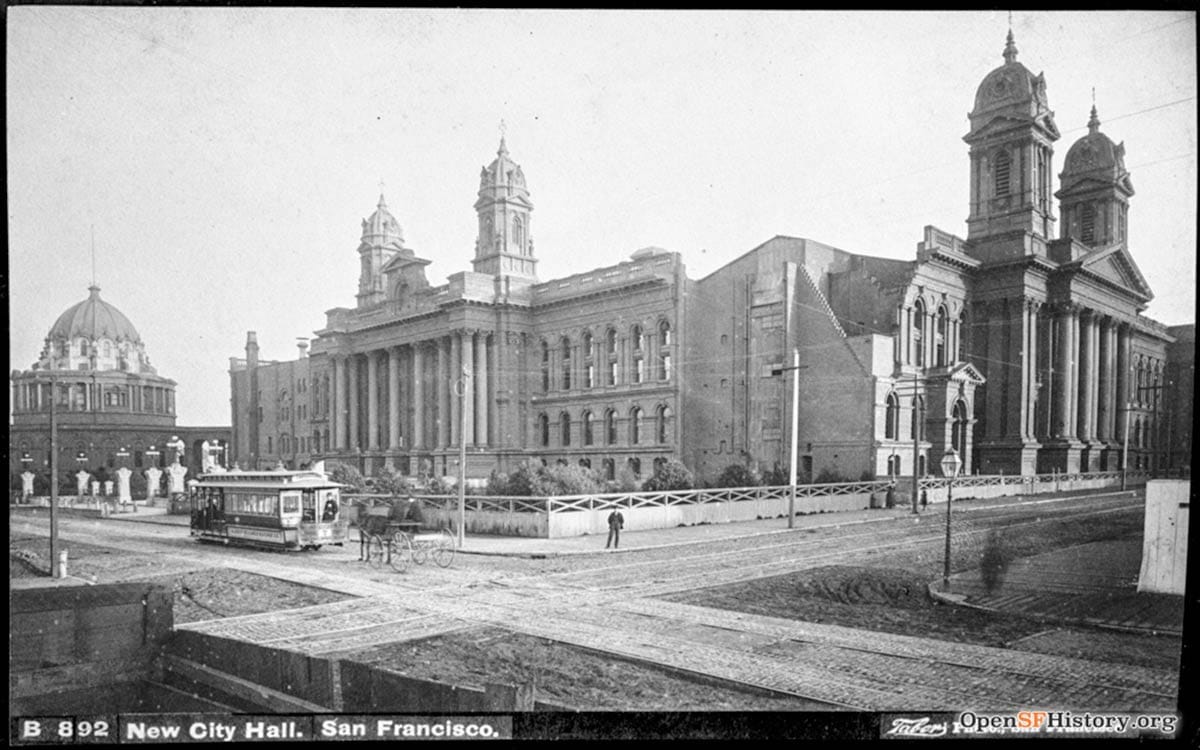

The old City Hall complex was a collection of grand buildings set in a triangle between Market, McAllister, and Larkin streets, where a good portion of the main library stands in 2026.

In 1890, it was already seen by many as a ever-growing and never-finished monument to government corruption and ineptitude.

Project construction began in 1870 and wasn’t completed until after almost 30 years of insider pay-offs, multiple architects, and shoddy workmanship. Less than a decade after the civic souffle was deemed finished, it fell to pieces in the 1906 earthquake.

There had already been two deaths in 1890 while constructing the Larkin Street wing in which Charles Meyers was working.

He would be the third.

One of the guy ropes to the girder-lifting derrick slipped. The main mast tipped. The massive timber boom came down—straight upon the head of Nettie’s father.

“All that was left of the sturdy rigger was a mangled and bloody corpse,” reported the Call. “He leaves a widow and four children.”

No Escape

The funeral took place on Sunday, two days after the horrible accident. At 1 pm, Charles’ lodge brothers met to remember him at the Red Men’s Hall at 320 Post Street. At 2pm, the services were held at the Meyers’ home in South of Market. Then Charles Meyers was buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery in the Richmond District.

Everything had changed on that Friday afternoon. Monday morning, just when father should be up to start a new work week, there was no father anymore.

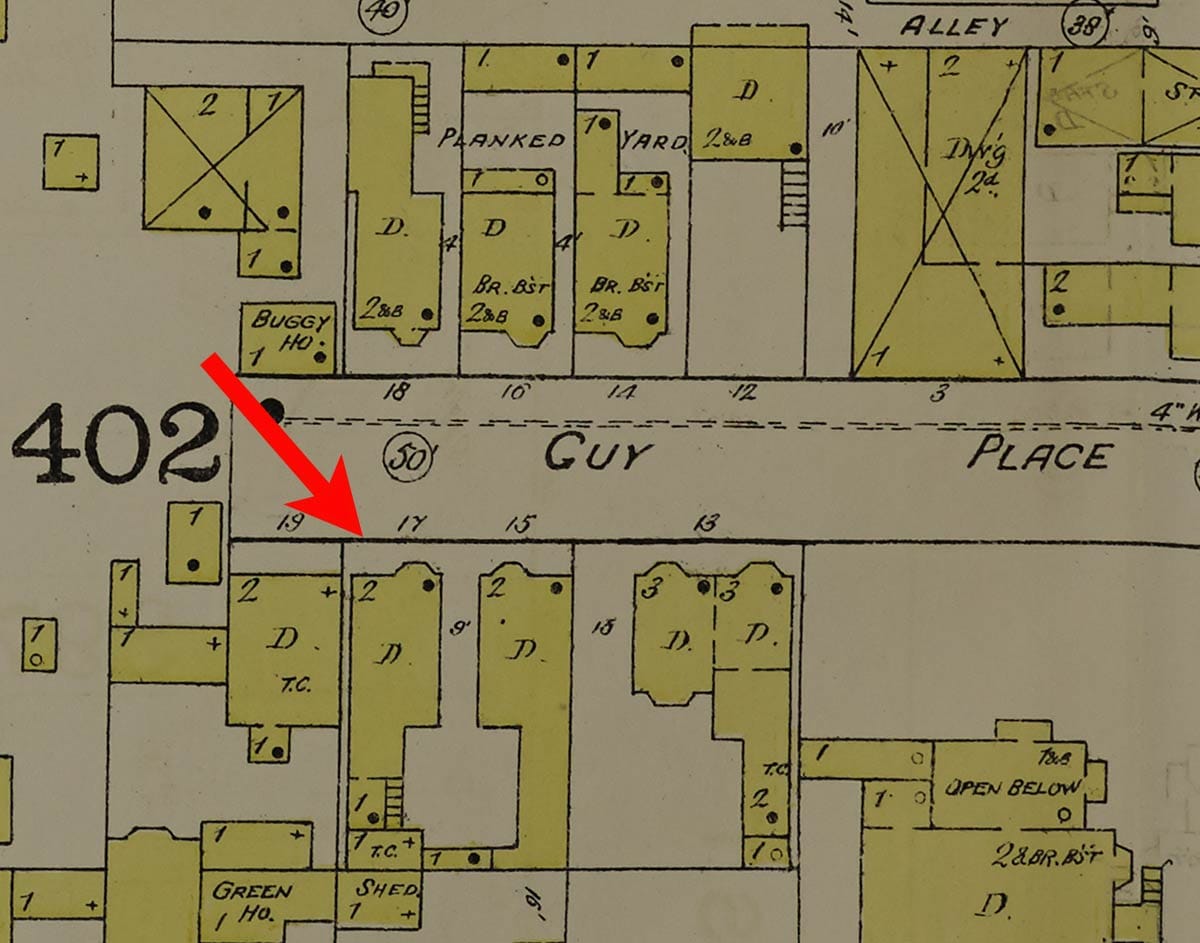

Nettie, her mother, and her older siblings—Carrie, Walter, and Charley— were now alone at the house at 17 Guy Place, a dead-end alley off First Street between Folsom and Harrison streets.

The block was fairly respectable for the neighborhood, but the smokestack effluvia from surrounding foundries, paint factories, mills, and gas extraction companies filled the air. Alleys were packed with laboring families, itinerant workers, and disease. The city health officer had just declared South of Market as San Francisco’s most unsanitary neighborhood.

Nettie’s mother, Annie, now a 32-year-old widow, decided to rent the Guy Place house and take her children away from industrial South of Market and the ghosts it held. The Meyers family moved across the bay to a tidy bungalow on 1531 Sherman Street in Alameda.

Tragedy stayed on their trail.

Just two and a half years after her father’s accident, Nettie’s 16-year-old sister, Carrie, died of a heart problem. Oldest brother Walter went next, of lung trouble, when he was just 20.

South of Market’s hooks wouldn’t let go. With what feels like some fatalism, Annie Meyers abandoned Alameda after her son’s death and retreated with Nettie and Charley back to Guy Place.

In May 1902, less than a year and a half after returning to San Francisco, Annie herself, 44-years-old, died of kidney disease.

Shortly before passing, perhaps seeking some security for 12-year-old Nettie and 17-year-old Charley, she married a neighbor, a boilermaker named Thomas H. Delehanty. A year later, this stepfather was also dead.

South of Market life was unforgiving.

Working-class people were always more susceptible to disease and accidents, especially in the 19th century, but Death seemed to have a personal interest in the Meyers family.

Nettie and Charley were now on their own.

New Life

The probate court settled Annie’s estate and gave guardianship of Nettie to the Meyers’ neighbor on Guy Place, Ruth Neate, who was my great-great-grandmother.

Ruth and my great-great-grandfather Luffman had five kids of their own and Nettie was instantly family. Charley, who was learning the blacksmith trade, also lived with the Neates.

The whole blended brood were burned out of South of Market because of the 1906 earthquake and fire. In the 1910 US Census, both the surviving Meyers were listed as children of the Luffman and Ruth Neate family, all living at 402 Sanchez Street near Mission Dolores.

Nettie graduated from high school, got a job as a telephone operator, and when she married Jesse Miller at 22 years old (under the name Nettie Neate Meyers), she chose my great-grand-aunt, Iris, as her maid of honor.

The last link of chain to her former life snapped while Nettie was still a newlywed. Charley died in September 1913 at just 28 years old.

Now she was the last Meyers, and despite her husband and adopted family, there must have been some foreboding in her heart that Death had almost run out of targets. She was the youngest. She was the last.

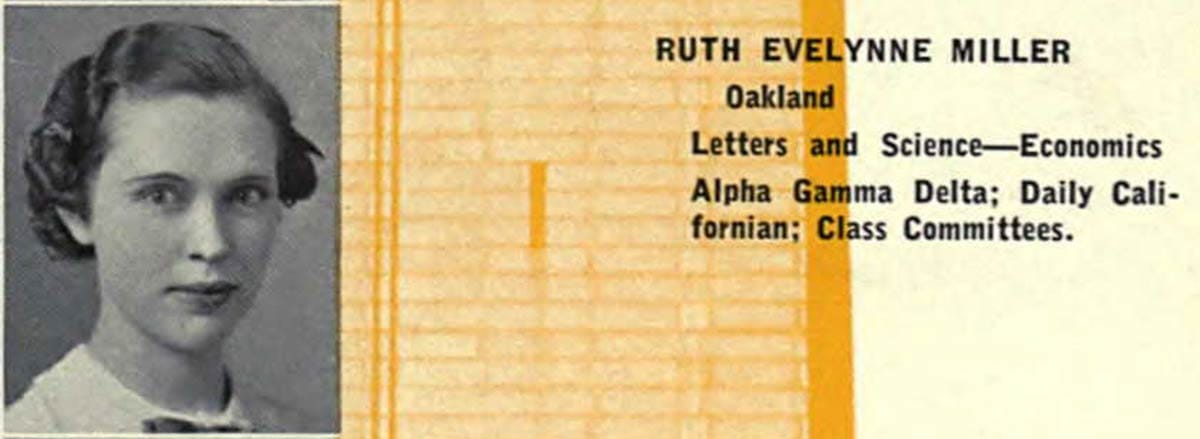

On my grandfather’s first birthday in 1914, Nettie is the one holding him up. In 1916, she had her own child, Ruth Evelynne Miller, who may have been named after her stepmother, my great-great grandmother Ruth Neate.

Nettie’s husband advanced from warehouse work to management and the family moved to the East Bay in the early 1920s. There were no other children for Jesse and Nettie, but daughter Ruth was bright and she thrived. In 1938, she graduated from UC Berkeley and started a career in the publishing business. She later was BART employee #13.

The years slipped past and it must have seemed incredible to Nettie how far she was from her dark South of Market days as she turned 40, 50, and then 60 years old.

For the era, Nettie’s daughter Ruth married fairly late at 34 years old in 1951 to James Colin Bayless, “her one true love.” The couple didn’t give Nettie grandchildren, but lived nearby in Oakland.

Jesse Miller passed away at 86 in 1970, a long life for that generation. Nettie celebrated her 80th, then her 90th birthdays, ridiculous numbers considering none of her siblings lived older than 28 and that both her parents died in their 40s.

She would go on to outlive all of her Neate step-family members and almost surpassed my grandfather—the toddler she posed with as a young bride—when she passed away at 92 years old in January 1982.

Last to Know

Nettie’s daughter Ruth inherited her mother’s longevity and even beat her by a year, dying in 2010 at 93 years old. She had no children, no close relatives after her husband died, but Ruth had a wide circle of friends and work colleagues, and kept busy with charitable endeavors.

Her obituary mentioned one aged cousin in Indiana, related through her father’s side, but it seems unlikely any one in the Midwest remembers Ruth or her mother Nettie today.

As the family member interested in the past, I am the inheritor of old scrapbooks and letters. I learned Nettie’s name from Iris Neate’s son while looking at old snapshots. He passed away a year or so after that meeting.

My curiosity over the years sent me into old newspapers, pushed me to track down marriage and death certificates, obituaries, and ephemera, which, together, draw the lightest outline of Nettie’s life.

Staring at her photo, feeling my own years building up on me, I can’t help but feel melancholic over the millions of unrecorded lives in San Francisco’s history, the fading of the last survivors, the final memory-keepers.

I am almost certainly the only one, the last to know, of the tragic youth, then the very long and apparently loving and satisfactory life, of Nettie Meyers Neate Miller.

That is, I was the only one.

Then you read this story.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

Even if you never chip in to the beverage fund, you can reap its benefits. (Having a free drink with me and swapping stories of our misspent youths... or a more elevating subject of your choice.)

Let us get out and sponge up the cultural riches of this amazing city, shall we? When are you free?

Sources

“Crushed to Death,” San Francisco Call, September 19, 1890, pg. 7.

“The Board of Health,” San Francisco Examiner, August 8, 1889, pg. 2.