The White House

Remembering a store and a man that every San Franciscan once knew.

We were downtown and one of our group asked about a handsome curved building on the southeast corner of Sutter Street and Grant Avenue.

“That’s the White House,” I answered, surprised. “You know, the old department store?”

And I immediately thought, of course, they probably didn’t know, as the White House closed in 1965, the year I was born and I only knew about it from older people telling me. Also, being in her 20s, my interlocutor may not even have a clear idea what a “department store” was.

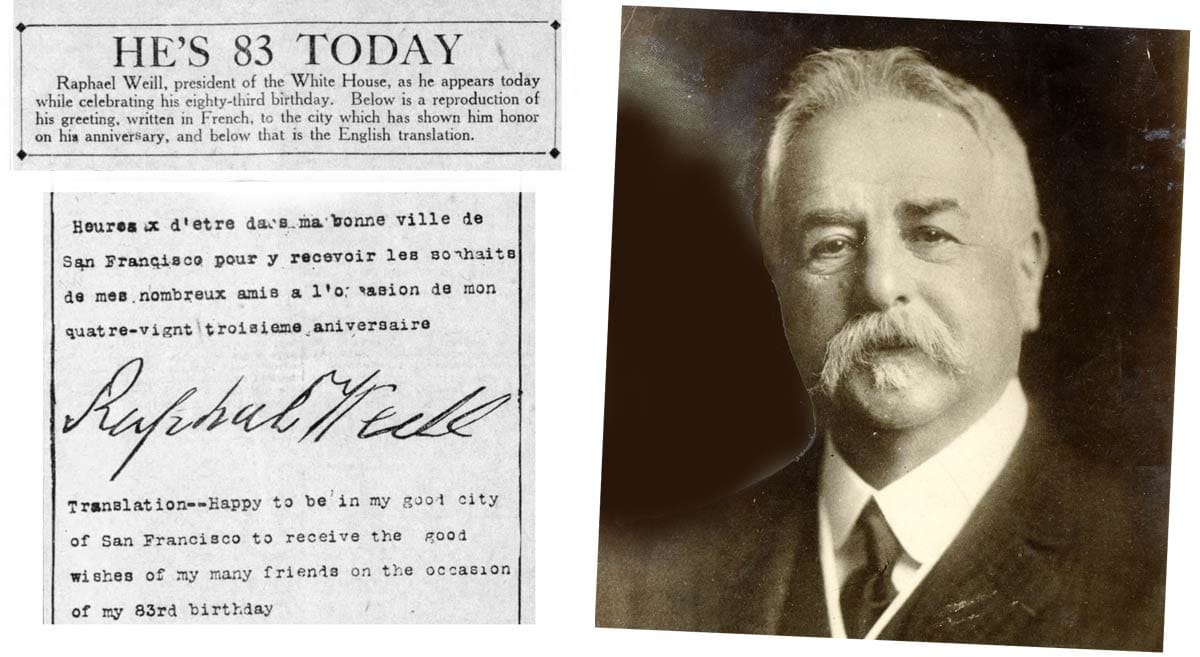

The name of Raphael Weill, the man who created and ran The White House, wasn’t worth bringing up at all, although there were many decades in San Francisco’s history when everyone in the city knew his name.

Maison Blanche

In 1854, Raphael Weill, a Jewish teenager from Phalsbourg, France, arrived in San Francisco and found a position at the Sacramento Street dry goods store of Davidson and Lane, which dealt primarily in lace, ribbons, napkins, table linens, bed sheets, and hosiery.

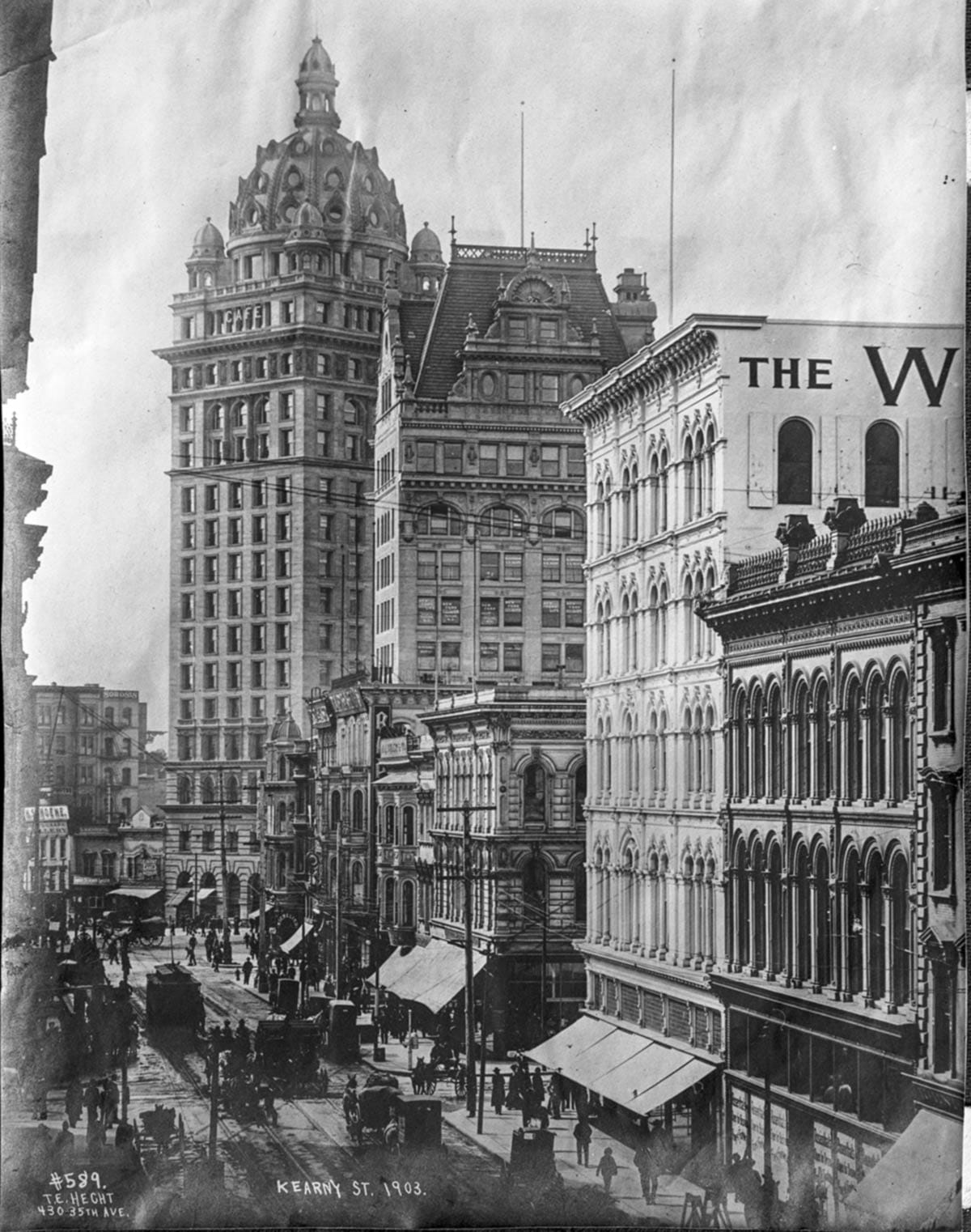

Many of San Francisco’s finest and most fashionable stores were started by French entrepreneurs importing the best from Paris. Davidson and Lane were not French, and did not speak French, but Weill was and did. The business prospered and moved first to Montgomery Street, and then, as the city’s retail district shifted west, to its own handsome building on the corner of Kearny and Post streets in 1870.

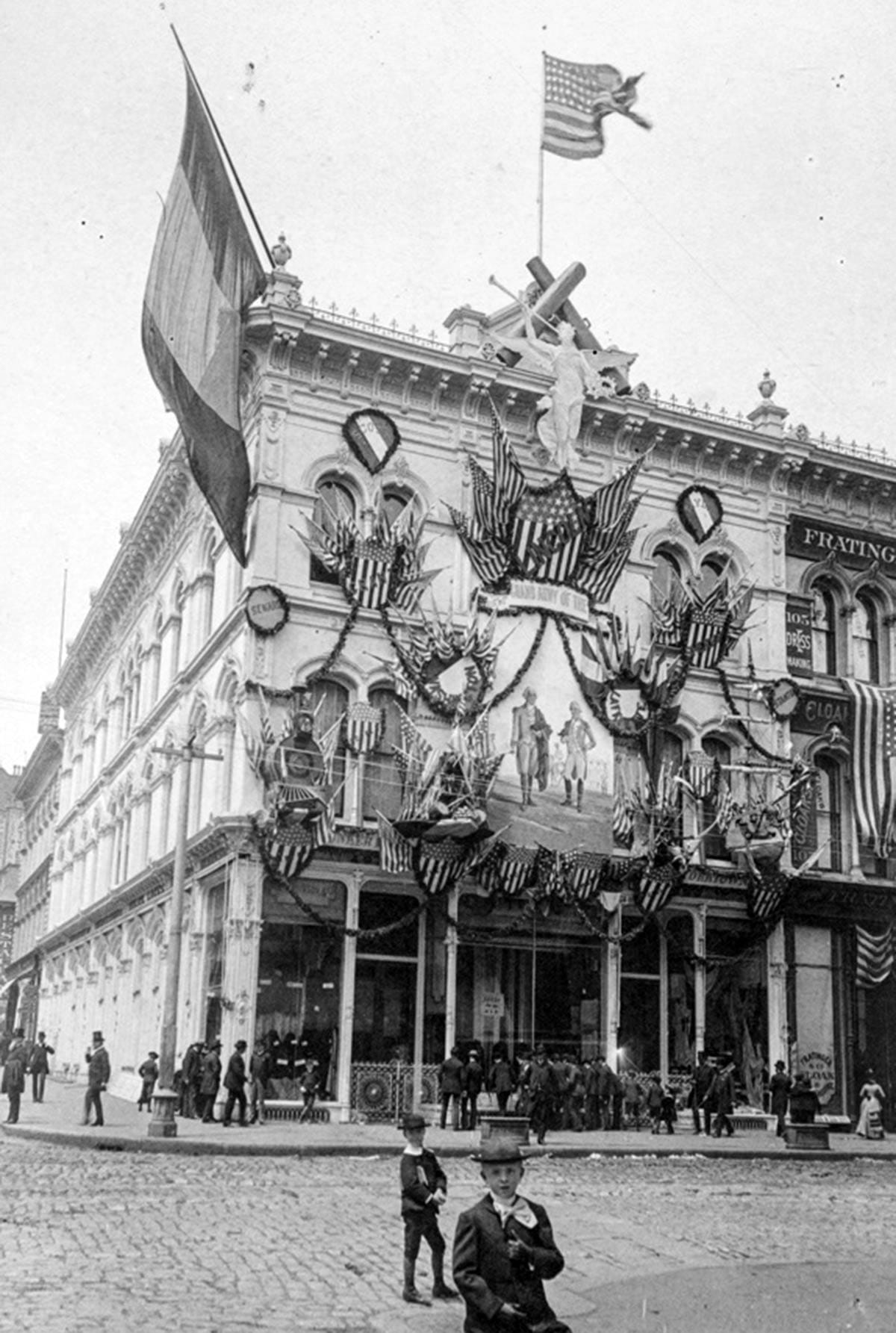

Weill bought out his partners and, inspired by the Maison Blanche store in Paris, rebranded the business as The White House. White goods were a specialty: snow white gloves, table clothes, and undergarments conveying elegance, refinement, and Victorian cleanliness. The store on the corner of Post and Kearny streets practically glows in old photographs:

The last decades of the 19th century saw the birth and boom of department stores, where the most successful specialists were able to leverage service and the loyalty of customers to expand their offerings.

By the late 1880s, The White House had grown beyond linens and stockings to offer the latest fashions with a 150-seamstress dressmaking staff. Along with feather boas, hats, perfumes, and gloves, The White House soon offered toys, suitcases, and dozens of flatware and serving-dish patterns.

The 1870 building was expanded and two more floors were added just at the turn of the 20th century:

The White House was incinerated in the fires following the 1906 earthquake, but San Francisco’s elegant shopping emporiums rebounded quickly from the disaster by setting up temporary quarters along Van Ness Avenue.

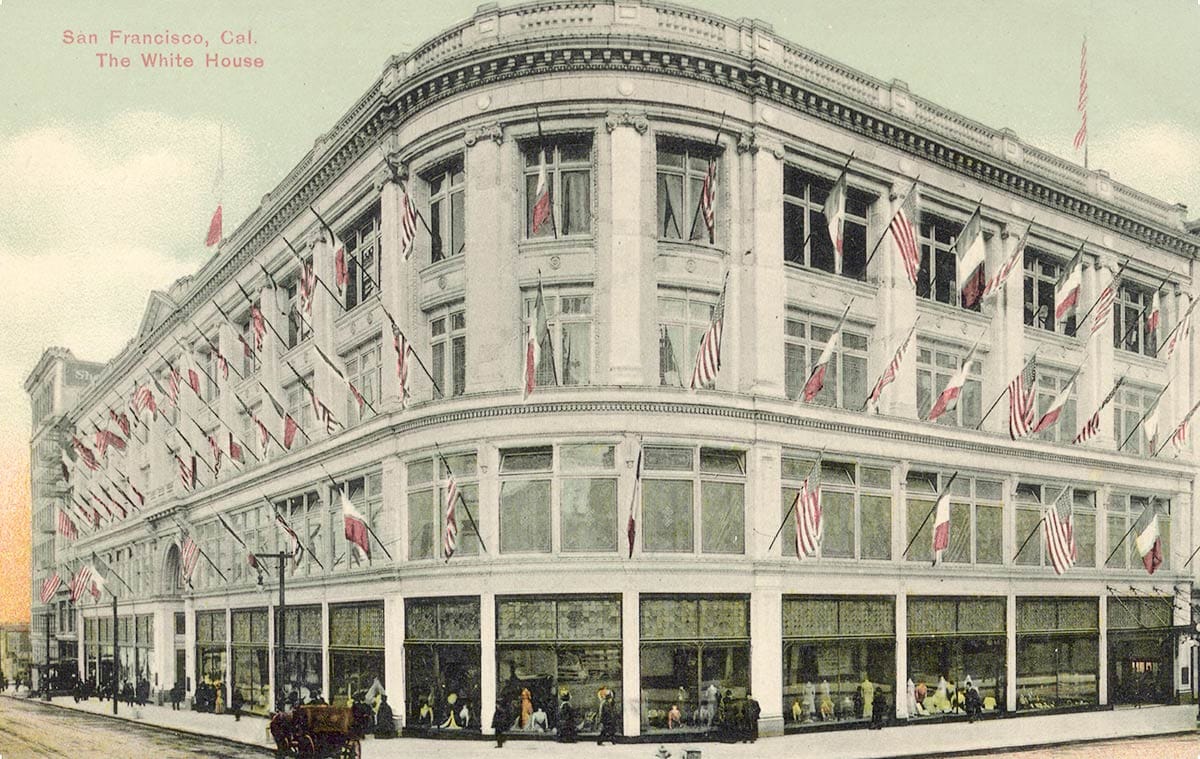

The White House returned to the Union Square area in a beautiful new cathedral of commerce centered on Sutter Street and Grant Avenue, re-opening on March 13, 1909.

I am a sucker for the designs of the architect Albert Pissis. His White House building gracefully gives way in a curve along the corner of Grant Avenue. Display windows make up the base of the building, enticing and leading you along. Pissis’s balustrade cornice is like a filigreed crown. The whole effect is one of a patisserie confection too nice to eat.

Entering the rambling complex was an elevated version of entering a modern galleria mall, but all “departments” were under one management and Raphael Weill was likely somewhere on a floor to greet you.

Beloved Citizen

Weill lived most of his life at the all-male Bohemian Club. He had a faithful valet/assistant “who was his constant shadow.” He never married and described himself as confirmed bachelor. While gregarious and an excellent host of regular Sunday breakfasts (which never began before noon), he was private about personal details.

Some quiet assumptions we might have about him today could have been quiet assumptions people had about him then. What was said publicly was that Weill was a leading citizen of the city, a generous, civic-minded lion of a man.

Weill was French, a chevalier of the French Legion of Honor, but also passionately American and Californian. Each year he closed The White House on Lincoln’s birthday and Admission Day. He pushed for American flags to be flown at every public school.

Weill gave to charities for French orphans. He gave to the French Hospital. Weill gave to create a fund to recognize the bravery and service of the city’s fire department. Weill gave away clothing to thousands of refugees after the 1906 earthquake and fire. Weill gave his time as a school board member. Weill gave to his native country when it was under attack in World War I and spent most of the war in Paris doing relief work while in his 80s.

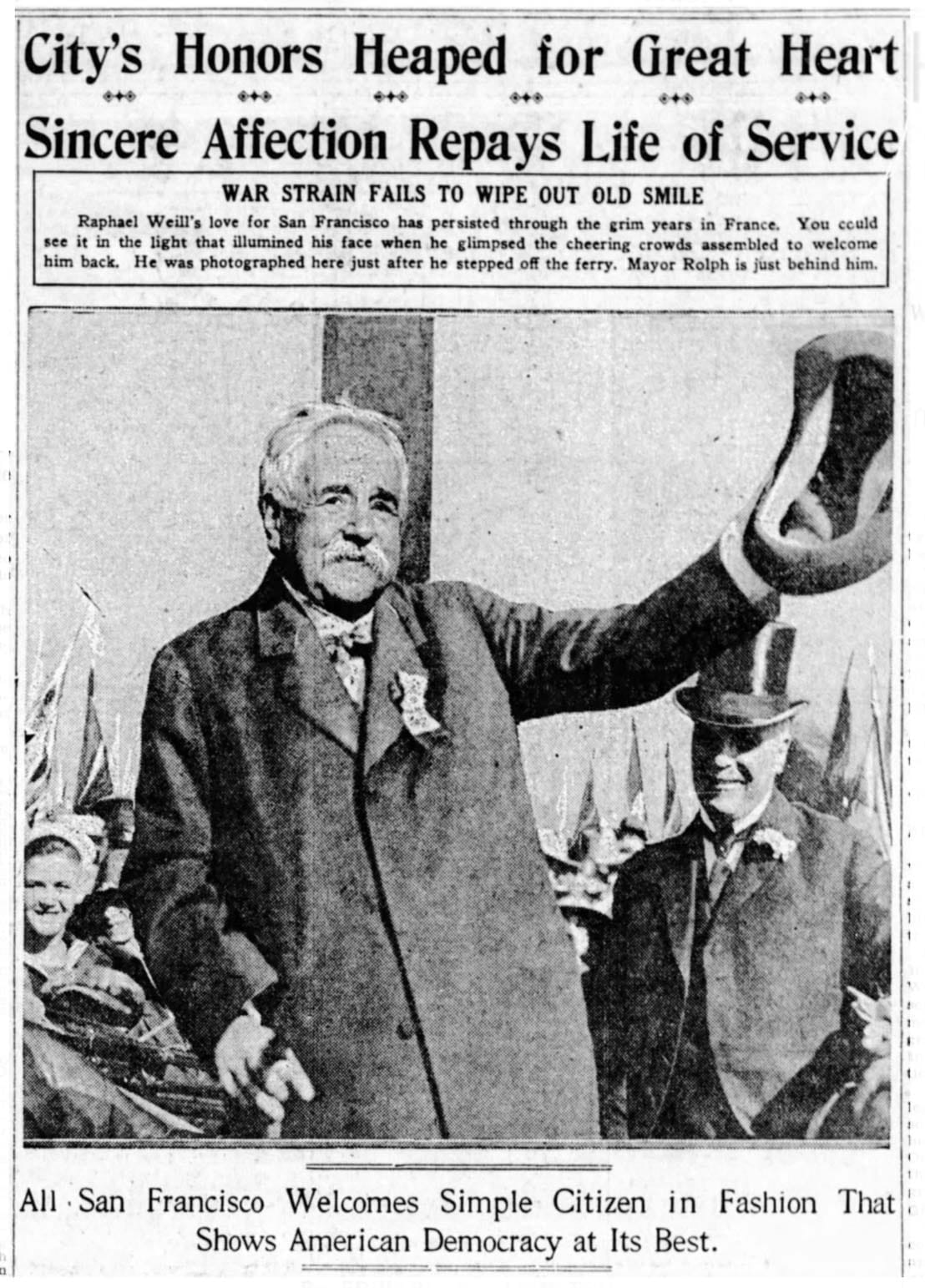

When Raphael Weill returned from France in 1919, his ferry was met by the mayor and 800 White House employees waving tiny French and American flags. He was whisked off to four official receptions, given a gold plate with an inscription hailing him as “Friends of Humanity, Upholder of Liberty and Right, Beloved Citizen of our City!” He was all over the newspapers the next day.

Everyone seemed to love the merchant prince. “[H]e hasn’t a single enemy […] every man, woman and child feels that he is a friend.”

Raphael Weill died in 1920 while in Paris and is buried there. San Francisco, the city he made his home and which considered him one of their greatest citizens, began raising money for a memorial to honor him.

Forgetting

The monument to Weill ended up as a casting of Auguste Rodin’s The Three Shades, which was presented at the Legion of Honor in 1925 accompanied by a Haig Patigian plaque commemorating the man. A public school in the Western Addition was named after Weill. His estate and nephew kept giving by funding a new wing of the French Hospital in the Richmond District in 1937.

But we tend to forget.

The Legion of Honor plaque is in storage. Raphael Weill school was renamed for Rosa Parks in the 1990s (an early education program at the campus still bears Weill’s name). French Hospital was rebuilt in 1963 and later subsumed into the Kaiser system. The memorial plaque for the old Weill wing might be mounted somewhere inside. I haven’t found it yet.

Personal honors and legacy aside, Raphael Weill believed The White House would go on “indefinitely.” When he died, his nephew took the reins of an impressive operation employing a thousand people and covering four buildings in the heart of San Francisco’s retail quarter.

It was only after World War II that The White House began to teeter. Tastes changed, management changed, expansion plans to Oakland were not successful. New malls like Stonestown and other suburban shopping centers ate into The White House’s bread and butter offerings.

In 1965, The White House gave up the ghost. A few years later a big chunk of the Pissis building was converted into a parking garage.

Other giants of San Francisco department store history are also gone: City of Paris, I. Magnin, Joseph Magnin, Gump’s. My working-class ancestors were Emporium people (gone). My grandmother occasional dragged me through Roos-Atkins (gone), and we gawked around post World War II interloper Macy’s, which is now on its way out of town.

City leaders are trying to respond to these losses and the changing culture of shopping by encouraging more housing to be introduced downtown and around Union Square.

I wonder that the owners of The White House complex, one of most attractive buildings in the area, haven’t investigated turning it into residential units.

Perhaps today many San Franciscans aren’t interested in being associated with anything named The White House.

Woody Beer and Coffee Fund

It may be a futile belief we can shape how people remember us when we are gone. But if I am memorialized only as the guy who always bought someone’s drink I would die happy. Thanks to a Jamie N. (F.O.W.) tip this week, that dream continues. (I suppose Jamie is really buying the next drink...)

You can buy into a small part of this legacy project, either by chipping in or letting me know when you are free to be treated.

Sources

Edward H. Hamilton, “City’s Honors Heaped for Great Heart,” San Francisco Examiner, July 11, 1919, pg. 11.

“Raphael Weill is Called by Death in Paris,” San Francisco Bulletin, December 10, 1920., pg. 1.

“S.F. Dedicates Memorial to Noted Citizen,” San Francisco Examiner, February 26, 1925, pg. 9.

Anne Evers Hitz, Lost Department Stores of San Francisco (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2020)